A study just out in Nature, coauthored by Soloman Hsaing, Kyle Meng and Mark Cane, finds El Nino events are correlated civil conflict. Sol is a recent Columbia PhD who has been working as a post doc on an NSF grant I have with Wolfram Schlenker and David Lobell.

What makes the study interesting is that it documents a link between conflict and weather fluctuations that are predictable and larger-scale--a bit closer to climate change. That could be a lot different than documenting a links between conflict and localized acute weather events.

The study is featured on the cover of Nature and is getting a ton of press coverage.

Here's a nice summary at Time.

Here's another at the Washington Post.

I don't think anyone knows what to make of the correlation. The only mechanism that obviously comes to mind is food prices. But I've never played around with conflict data. And it's amazing how playing around with the data can change one's perspective on things. Someday... Right now I have too many old and ongoing projects to finish up and get out the door.

Update: The Economist is currently featuring this work on its front page, along with some past work by my colleagues and myself.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Food Prices and Riots

For a long while now I've been wanting a student to do some work on the link between food prices, riots and other kinds of conflict. I've got a few basic ideas about how this could be done. But I'm also busy and am sure a zillion others are busy working on this too.

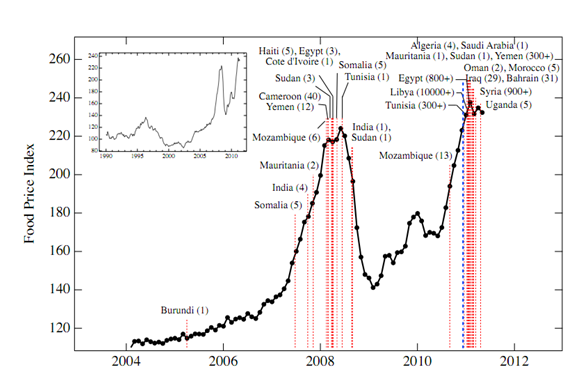

So, one of my students, Jon Eyer, just sent me this link. I don't know exactly what these folks are doing or where they got their data. But the graph, reproduced below, sure is compelling. We have had a few papers linking weather to conflict. It seems to me the obvious mechanism in those papers was food prices. So why haven't more people looked at food prices themselves?

And since climate change may cause food prices to rise, Eric Hammel over at Thomas Ricks' FP blog is connecting the dots to argue that climate change is the biggest national security challenge we face.

That might be overstating the case. But this does seem like a very real threat.

Update: Marc Bellemare, who made a comment below, has a very nice new paper on this topic. (Marc, is your paper posted somewhere? Do you want to post a link?)

While I haven't looked at this data or model carefully, it seems to me that the correlation--if real--is fairly convincing evidence of causality going from food prices to riots. We all saw the events leading to price fluctuations shown in the graph. It's pretty clear to me--and I think to anyone who followed this stuff--that events in Africa did not cause the price spikes. We had bad weather in Australia, Russia, China and other places. We had rapidly growing demand in Asia. We had ethanol. Then we had a series of rice export bans. Then we had the fires and export bans in Russia. Africa is way too small in terms of food demand and supply to markedly affect world food prices--which is what the graph seems to show--for causation to be going from conflict to prices. Any other non-causal association would have to come from some third factor that happened to be correlated with both conflict and food prices. It's hard for me to imagine what that third factor would be and what the mechanism would be.

Anyway. I'm sure there are plenty of interesting ways to look at this issue and to really get our heads around it I think we should take stock of all of them.

So, one of my students, Jon Eyer, just sent me this link. I don't know exactly what these folks are doing or where they got their data. But the graph, reproduced below, sure is compelling. We have had a few papers linking weather to conflict. It seems to me the obvious mechanism in those papers was food prices. So why haven't more people looked at food prices themselves?

And since climate change may cause food prices to rise, Eric Hammel over at Thomas Ricks' FP blog is connecting the dots to argue that climate change is the biggest national security challenge we face.

That might be overstating the case. But this does seem like a very real threat.

Update: Marc Bellemare, who made a comment below, has a very nice new paper on this topic. (Marc, is your paper posted somewhere? Do you want to post a link?)

While I haven't looked at this data or model carefully, it seems to me that the correlation--if real--is fairly convincing evidence of causality going from food prices to riots. We all saw the events leading to price fluctuations shown in the graph. It's pretty clear to me--and I think to anyone who followed this stuff--that events in Africa did not cause the price spikes. We had bad weather in Australia, Russia, China and other places. We had rapidly growing demand in Asia. We had ethanol. Then we had a series of rice export bans. Then we had the fires and export bans in Russia. Africa is way too small in terms of food demand and supply to markedly affect world food prices--which is what the graph seems to show--for causation to be going from conflict to prices. Any other non-causal association would have to come from some third factor that happened to be correlated with both conflict and food prices. It's hard for me to imagine what that third factor would be and what the mechanism would be.

Anyway. I'm sure there are plenty of interesting ways to look at this issue and to really get our heads around it I think we should take stock of all of them.

Monday, August 22, 2011

Hotter Planet Doesn't Have to Be Hungry

I'm live at Bloomberg. The usual bailiwick about weather, crop yields and food prices.

My suggested title was: "On the Precipice of a Warming World: Will We Feed Everyone?"

It's interesting how a title can change the tone from one that leans dismal to one that seems optimistic.

Update:

I basically gave three policy suggestions in my Bloomberg piece. What else might I suggest? Well, I find myself in the blurry area of my career that lies between focusing on positive "what is" kinds of questions and normative "what should we do" kinds of questions. I'm still much more comfortable entertaining questions of the "what is" variety, so policy ideas come slowly.

With that caveat in mind, here are four (or three and one-half) policy ideas that I didn't mention in the Bloomberg piece.

1) End ethanol subsidies and mandates. There has been some talk of ending the subsidy, but I think that would be meaningless from a food price perspective unless the mandates were also ended. I'm not at all confident about the political feasibility of such a plan.

2) If ethanol subsidies/mandates cannot be ended completely, perhaps Congress could make mandates and subsidies contingent on price. The idea is to have a safety valve of sorts, so that if prices hit some announced threshold the mandate and subsidies would be curtailed.

3) Develop international agreements that would ensure reasonably low food prices for the world's poorest in exchange for keeping trade open. The idea here would be to reduce the likelihood of export bans and reduce inventories held in speculation of possible future export bans.

4) Similar to point 2, we could make the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) contingent on price. The CRP, which I've written about before, basically pays farmers not to plant crops and establish natural wildlife habitat, buffer strips, etc. We have about 30 million acres in the program right now--nearly the size of North Carolina. CRP contracts could be written with an escape clause that allows farmers to exit the contracts early if prices get high enough. This would probably make CRP cheaper in the first place, since farmers would be more willing to enroll, and would help to relieve prices when they get too high.

My suggested title was: "On the Precipice of a Warming World: Will We Feed Everyone?"

It's interesting how a title can change the tone from one that leans dismal to one that seems optimistic.

Update:

I basically gave three policy suggestions in my Bloomberg piece. What else might I suggest? Well, I find myself in the blurry area of my career that lies between focusing on positive "what is" kinds of questions and normative "what should we do" kinds of questions. I'm still much more comfortable entertaining questions of the "what is" variety, so policy ideas come slowly.

With that caveat in mind, here are four (or three and one-half) policy ideas that I didn't mention in the Bloomberg piece.

1) End ethanol subsidies and mandates. There has been some talk of ending the subsidy, but I think that would be meaningless from a food price perspective unless the mandates were also ended. I'm not at all confident about the political feasibility of such a plan.

2) If ethanol subsidies/mandates cannot be ended completely, perhaps Congress could make mandates and subsidies contingent on price. The idea is to have a safety valve of sorts, so that if prices hit some announced threshold the mandate and subsidies would be curtailed.

3) Develop international agreements that would ensure reasonably low food prices for the world's poorest in exchange for keeping trade open. The idea here would be to reduce the likelihood of export bans and reduce inventories held in speculation of possible future export bans.

4) Similar to point 2, we could make the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) contingent on price. The CRP, which I've written about before, basically pays farmers not to plant crops and establish natural wildlife habitat, buffer strips, etc. We have about 30 million acres in the program right now--nearly the size of North Carolina. CRP contracts could be written with an escape clause that allows farmers to exit the contracts early if prices get high enough. This would probably make CRP cheaper in the first place, since farmers would be more willing to enroll, and would help to relieve prices when they get too high.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Debating Illegal Labor at the New York Times

"Could Farms Survive Without Illegal Labor?"

I'm one of several debaters. I like what Phillip Martin had to say--he's the real expert here. Here's the intro to the broader debate:

There is an old and largely true hypothesis in economics: supply creates its own demand. With regard to low-skilled immigration, one particularly compelling test of this hypothesis is an old study by David Card that examined the unemployment and wage effects of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami labor market (PDF). That unusual event brought about 125,000 low-skilled laborers to Miami over just a few months, about a 7% increase in the local labor market. You might think that such an event would have caused wages to fall and unemployment to skyrocket. But it didn't. Neither wages nor unemployment changed.

Now, things are probably different in an environment with high unemployment. Standard theories of recessions are the clearest exception the rule that supply creates its own demand. But shifting supply inward--which is effectively what getting tough illegal immigrants amounts to--seems like a really bad way to deal with unemployment relative to finding a way to shift demand outward.

I'm one of several debaters. I like what Phillip Martin had to say--he's the real expert here. Here's the intro to the broader debate:

A farmer in Maine who is raising crops sustainably told Times columnist Mark Bittman, “If the cost of food reflected the cost of production, that would change everything.” Instead, American produce is underpriced, in part because farmers and growers rely on illegal immigrant workers, who are paid little and often have poor working conditions.

This reliance on immigrant workers has farmers lobbying against a bill that would require them to verify migrant workers' status and employ only legal workers, saying such a mandate would cripple the industry.

If American growers are so dependent on illegal labor, would strict verification drive up prices for labor and, ultimately, produce? Are consumers too accustomed to inexpensive vegetables and fruit to accept the cost of legal labor to produce it?I've already received email complaining about my remarks to the effect that getting rid of illegal immigrants would do little for the ranks of unemployed legals seeking work.

There is an old and largely true hypothesis in economics: supply creates its own demand. With regard to low-skilled immigration, one particularly compelling test of this hypothesis is an old study by David Card that examined the unemployment and wage effects of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami labor market (PDF). That unusual event brought about 125,000 low-skilled laborers to Miami over just a few months, about a 7% increase in the local labor market. You might think that such an event would have caused wages to fall and unemployment to skyrocket. But it didn't. Neither wages nor unemployment changed.

Now, things are probably different in an environment with high unemployment. Standard theories of recessions are the clearest exception the rule that supply creates its own demand. But shifting supply inward--which is effectively what getting tough illegal immigrants amounts to--seems like a really bad way to deal with unemployment relative to finding a way to shift demand outward.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Does GMO Regulation Enhance Monsanto's Market Power?

I've been wondering for a little while about Monsanto's growing market power in the seed business. Monsanto's growing dominance has coincided with expansion of genetically modified seed. That doesn't mean one caused the other. But there may be a causal link that comes from strong regulation of GMOs relative to traditionally bred crops. This regulation makes it too costly for small or public entities--like universities--to develop GMO seeds and take them to market. The only way to do it is to be really big and have deep pockets like Monsanto does.

This has been the complaint of Ingo Potrykus, who in 1999 invented "golden rice," a genetically modified crop fortified with vitamin A. Potrykus has been working ever since to get the product approved internationally. He would like to help some of the millions that die or become afflicted with blindness due to vitamin A deficiency. Clearly, there is not much money in selling seeds to poor people, so this is not a business Monsanto would get into. And despite overwhelming evidence that golden rice is safe, it could still be another year or more--13+ years in total--before Potrykus gets his seed to market.

Coming back to Monsanto and their market power: The key thing here that worries me is that commodity demand is very inelastic. Prices are super sensitive to quantities. Thus, if Monsanto comes up with a higher-yielding seed and sells it on the same scale it currently sells its various Roundup-Ready (herbicide resistant) varieties, then commodity prices would fall. Possibly by a lot. That would be a good thing for consumers around the world and particularly good for the world's poorest. But as with golden rice, I worry that Monsanto recognizes that it's not in their interest to develop and navigate a high-yielding GMO crop through the bureaucratic regulatory maze. Because if they did, they would cannibalize their own profits by driving down commodity prices and thus the amount they could charge farmers for seed.

The most profitable approach for a dominant seed producer is to develop seed that extracts rents from other input providers. It therefore makes sense that they would build pesticides and herbicide resistance into plants rather than boost heat tolerance, for example. The current line of GMO crops increase their share of the seed market, helps them sell more Roundup, but they probably don't do much to boost yield and drive down commodity prices.

I'm not the kind of person who is knee-jerk anti-regulation. But in the case of GMOs, I think the world has gone overboard with safety and process regulation. It's hard to know for certain but it looks like an unintended consequence of this regulation has been to concentrate the seed business. And that concentration, in turn, may be skewing innovation in ways that are lot less socially useful.

Update: Readers may be interested in this article by David Zilberman, who was one of my professors and a great mentor at UC Berkeley. David (I believe) also made a nice comment below. Some may think that this is some kind of paid endorsement of GMO. I can sympathize with that kind of cynicism. And in some contexts there may be an element of truth to it. But I think the reality may be that GMO regulation actually accentuated Monsanto's market power and influence. And people like David Zilberman and Ingo Potrykus really do have the public interest at heart. I'd like to think I do too. And no, I'm not on Monsanto's payroll. Actually, they don't seem real happy about my work.

This has been the complaint of Ingo Potrykus, who in 1999 invented "golden rice," a genetically modified crop fortified with vitamin A. Potrykus has been working ever since to get the product approved internationally. He would like to help some of the millions that die or become afflicted with blindness due to vitamin A deficiency. Clearly, there is not much money in selling seeds to poor people, so this is not a business Monsanto would get into. And despite overwhelming evidence that golden rice is safe, it could still be another year or more--13+ years in total--before Potrykus gets his seed to market.

Coming back to Monsanto and their market power: The key thing here that worries me is that commodity demand is very inelastic. Prices are super sensitive to quantities. Thus, if Monsanto comes up with a higher-yielding seed and sells it on the same scale it currently sells its various Roundup-Ready (herbicide resistant) varieties, then commodity prices would fall. Possibly by a lot. That would be a good thing for consumers around the world and particularly good for the world's poorest. But as with golden rice, I worry that Monsanto recognizes that it's not in their interest to develop and navigate a high-yielding GMO crop through the bureaucratic regulatory maze. Because if they did, they would cannibalize their own profits by driving down commodity prices and thus the amount they could charge farmers for seed.

The most profitable approach for a dominant seed producer is to develop seed that extracts rents from other input providers. It therefore makes sense that they would build pesticides and herbicide resistance into plants rather than boost heat tolerance, for example. The current line of GMO crops increase their share of the seed market, helps them sell more Roundup, but they probably don't do much to boost yield and drive down commodity prices.

I'm not the kind of person who is knee-jerk anti-regulation. But in the case of GMOs, I think the world has gone overboard with safety and process regulation. It's hard to know for certain but it looks like an unintended consequence of this regulation has been to concentrate the seed business. And that concentration, in turn, may be skewing innovation in ways that are lot less socially useful.

Update: Readers may be interested in this article by David Zilberman, who was one of my professors and a great mentor at UC Berkeley. David (I believe) also made a nice comment below. Some may think that this is some kind of paid endorsement of GMO. I can sympathize with that kind of cynicism. And in some contexts there may be an element of truth to it. But I think the reality may be that GMO regulation actually accentuated Monsanto's market power and influence. And people like David Zilberman and Ingo Potrykus really do have the public interest at heart. I'd like to think I do too. And no, I'm not on Monsanto's payroll. Actually, they don't seem real happy about my work.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

A Malthusian Who Knows Markets

From a profile of Jeremy Grantham published in the New York Times a couple days ago.

Here are a few snippets:

On his track record:

I'm noting Grantham track record and think he's making a lot of sense. But I wonder: How many connoisseurs of bubbles have worked to find the controls? That is, find the historical episodes where there was a rapid market adjustment that may have appeared to be a bubble to the rare connoisseurs but then it turned out not to be a bubble. After the fact, maybe all bubbles look alike. But looking at it from hindsight doesn't really count.

But now Grantham is saying this time is different:

But while I'm nowhere near as confident as Mr Grantham, it seems very possible to me that the long downward trend in commodity prices has reversed permanently.

Here are a few snippets:

On his track record:

Grantham has a long track record. He was right about indexing, an investment strategy he took a lead role in inventing, when everyone else assumed that you should try to beat the market rather than join it, and about the long rally in small-cap stocks in the early 1970s, the bond rebound in 1981 and the resurgence of large-cap growth stocks in the early 1990s. He was also, well in advance, right about one bubble after another: Japan in 1989, tech stocks in 2000, the U.S. housing market and financial markets and global equities in 2008 (in the wake of which, when investors were still reeling, he made a celebrated and early bullish call in a letter titled, Reinvesting When TerrifiedOn prognosticating and environmentalism:

When he reminds us that modern capitalism isn’t equipped to handle long-range problems or tragedies of the commons (situations like overfishing or global warming, in which acting rationally in your own self-interest only deepens the harm to all), when he urges us to outgrow our touching faith in the efficiency of markets and boundless human ingenuity, and especially when he says that a wise investor can prosper in the coming hard times, his bad news and its silver lining come with a built-in answer to the skeptical question that Americans traditionally pose to egghead Cassandras: If you’re so smart, how come you’re not rich?On climate change policy:

Grantham says that corporations respond well to this message because they are “persuaded by data,” but American public opinion is harder to move, and contemporary American political culture is practically dataproof [my boldface]. “The politicians are the worst,” he said. “An Indian economist once said to me, ‘We have 28 political parties, and they all think climate change is important.’ ” Whatever the precise number of parties in India, and it depends on how you count, his point was that the U.S. has just two that matter, one that dismisses global warming as a hoax and one that now avoids the subject.On bubbles and animal spirits:

Grantham, who says that “this time it’s different are the four most dangerous words in the English language,” has become a connoisseur of bubbles. His historical study of more than 300 of them shows the same pattern occurring again and again. A bump in sales or some other impressive development causes people to get excited. When they do, the price of that asset class — South Sea company shares, dot-coms — goes up, and human nature and the financial industry conspire to push it higher. People want to hear good news; they tend to be bad with numbers and uncertainty, and to assume that present conditions will persist. In the financial industry, the imperative to minimize career risk produces herd behavior. As John Maynard Keynes, one of Grantham’s heroes, put it, “A sound banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.” All these factors contribute to a surge of what Keynes called “animal spirits,” which encourages people to convince themselves that this time prices will just rise and rise.

I'm noting Grantham track record and think he's making a lot of sense. But I wonder: How many connoisseurs of bubbles have worked to find the controls? That is, find the historical episodes where there was a rapid market adjustment that may have appeared to be a bubble to the rare connoisseurs but then it turned out not to be a bubble. After the fact, maybe all bubbles look alike. But looking at it from hindsight doesn't really count.

But now Grantham is saying this time is different:

So it’s news when Grantham, who has built his career on the conviction that peaks and troughs will even out as prices inevitably revert to their historical mean, says that this time it really is different, and not in a good way. In his April letter, “Time to Wake Up: Days of Abundant Resources and Falling Prices Are Over Forever,” he argued that “we are in the midst of one of the giant inflection points in economic history.” The market is “sending us the Mother of all price signals,” warning us that “if we maintain our desperate focus on growth, we will run out of everything and crash.”That sounds even more pessimistic than me, especially that last sentence. Prices will rise, which will keep us from running out.

But while I'm nowhere near as confident as Mr Grantham, it seems very possible to me that the long downward trend in commodity prices has reversed permanently.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Can't Beat the Heat

Ahem.

Poor Weather Pushes Prices Up for Corn and Soybeans:

The growing season isn't over yet. USDA was too optimistic last year at this time. But I think that was mainly because the heat wave came after surveying for the August crop report was finished (about August 1). If the weather stays good from now until harvest I'd guess the forecast will be about right.

I should also note that at least some of the price bump today could have been a demand shock. Aggregate demand is highly uncertain right now and closely tied to the stock market, which spiked about as much as commodities.

Supply shifts in, demand shifts out, prices go boom!

Update: An interesting tidbit (maybe) for ag. commodity wonks out there: About a week before each USDA forecast comes out, a couple private-market forecasts can be purchased. I don't have links handy, but I suspect all the major commodity players do in fact buy these private market forecasts. Some analysis by Scott Irwin and Daryl Good at UofI shows that private market forecasts are as accurate as USDA forecasts. Still, USDA forecasts move the market quite substantially when they are announced. Why?

Well, it turns out that combining the private-market forecast and USDA forecasts gives a forecast that significantly beats both of them. That means the USDA forecast still contains a lot of information. It also means that the market "surprise" is something far smaller than what was announced, and smaller even than the difference between private-market and USDA forecasts. The implication of all this is that prices are even more sensitive to quantities than they may appear, and about twice as sensitive (I think) as Irwin and Good estimated.

Poor Weather Pushes Prices Up for Corn and Soybeans:

Prices for corn and soybeans jumped in commodities markets on Thursday after the Department of Agriculture said that the onslaught of bad weather, from heat and drought in some areas to heavy rains and flooding in others, would reduce yields for those critical crops.Okay, I'll try to not let this go to my head. But the heat really kills. Maybe not as much when it's wet. But it still kills.

The growing season isn't over yet. USDA was too optimistic last year at this time. But I think that was mainly because the heat wave came after surveying for the August crop report was finished (about August 1). If the weather stays good from now until harvest I'd guess the forecast will be about right.

I should also note that at least some of the price bump today could have been a demand shock. Aggregate demand is highly uncertain right now and closely tied to the stock market, which spiked about as much as commodities.

Supply shifts in, demand shifts out, prices go boom!

Update: An interesting tidbit (maybe) for ag. commodity wonks out there: About a week before each USDA forecast comes out, a couple private-market forecasts can be purchased. I don't have links handy, but I suspect all the major commodity players do in fact buy these private market forecasts. Some analysis by Scott Irwin and Daryl Good at UofI shows that private market forecasts are as accurate as USDA forecasts. Still, USDA forecasts move the market quite substantially when they are announced. Why?

Well, it turns out that combining the private-market forecast and USDA forecasts gives a forecast that significantly beats both of them. That means the USDA forecast still contains a lot of information. It also means that the market "surprise" is something far smaller than what was announced, and smaller even than the difference between private-market and USDA forecasts. The implication of all this is that prices are even more sensitive to quantities than they may appear, and about twice as sensitive (I think) as Irwin and Good estimated.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Cheap Stocks Part Duex

The other day I suggested a good index for the relative price of stocks was Robert Shiller's S&P 500 price to earnings ratio multiplied by the 10-yr real rate on treasury bills. When the index is much greater than one, stocks look expensive; when it is much less than one, stocks look cheap.

I couldn't easily construct a long series of that index because inflation-indexed treasuries haven't been around for a long time. So I used the nominal t-bill rate instead.

But if I were using the real rate, today that index would be negative, because the real rate today on 10-yr treasuries is now negative.

Relative to throwing money away, earnings on the S&P 500 look real nice.

And with negative real rates extending over 10 years, I, like many others, lament our misplaced focus on debt and deficits.

I couldn't easily construct a long series of that index because inflation-indexed treasuries haven't been around for a long time. So I used the nominal t-bill rate instead.

But if I were using the real rate, today that index would be negative, because the real rate today on 10-yr treasuries is now negative.

Relative to throwing money away, earnings on the S&P 500 look real nice.

And with negative real rates extending over 10 years, I, like many others, lament our misplaced focus on debt and deficits.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Is Food Demand Growth in Asia a Myth?

Jayati Ghosh has long detailed piece over at the Guardian's Poverty Matters Blog about world food prices. She argues forcefully that demand growth from China and India are not a driving force in rising food prices. Instead, she says, it's all about ethanol subsidies and speculation.

Ghosh presents a lot of convincing-sounding statistics. I think I've got a reasonably good feel for the data and what she presents does, I fear, gently mislead the reader. I don't disagree with everything she's saying but she's definitely overstating her case.

However, she does have me scratching my head to figure out the best way to put the various factors into clearer perspective. That's something I'll work on.

For now, a few key points:

1) Consumption does not equal demand. Demand is the whole schedule of consumption quantities across a whole range of prices, and holding all else the same. What's ominous is that Asian consumption is growing fairly fast despite rising prices and slowing population growth. That reflects increasing demand for American-like diets rich in animal products and processed foods (especially in China). That increasing demand is not going to slow down unless Asia's economic growth slows down, and I don't want that any more than I expect Ghosh does.

2) Ghosh discusses coarse grains but omits oil seed. The elephant in the room--which is closely connected to coarse grain markets--is soybeans. Soybean production is a big source of growth in staple food production and Asia is sucking it up, big time.

3) Yes, ethanol is a big deal. But that doesn't mean income growth in Asia isn't a big factor too.

4) Speculation has nothing to do with it. If speculation were a driving force, we would see inventory declines. Speculation can only cause prices to spike if it also causes inventories to accumulate. So whatever the contributions of the various factors, they are fundamental, not speculative. I've beat this horse many times, as have others who really know their stuff (Paul Krugman, Jim Hamilton at UCSD, Brian Wright at UC Berkeley, immediately come to mind).

I'm a bit concerned about they way Ghosh presents her data on consumption growth. First, by aggregating across decades and countries consumption is mostly inseparable from production. She shows growth rates for each in a series of decades, and the trend looks downward. That's basically because production growth has been approximately linear, so growth rates have declined as the baseline level production (the denominator) has grown larger. What's ominous is that bit of an increase in the recent decade: that's not production picking up but inventories getting drawn down, hence the price spike.

One thing I find a little strange is an apparent defensiveness on the part of some Asians about Asian demand growth. I, for one, don't blame them for their growth. Rather, I'm concerned that other poor nations (especially some African countries) are not growing as fast, and that many even in relatively rich and relatively growing countries seem to be left behind. We should worry about income inequality, especially in an environment with high and rising prices of food staples.

Ghosh presents a lot of convincing-sounding statistics. I think I've got a reasonably good feel for the data and what she presents does, I fear, gently mislead the reader. I don't disagree with everything she's saying but she's definitely overstating her case.

However, she does have me scratching my head to figure out the best way to put the various factors into clearer perspective. That's something I'll work on.

For now, a few key points:

1) Consumption does not equal demand. Demand is the whole schedule of consumption quantities across a whole range of prices, and holding all else the same. What's ominous is that Asian consumption is growing fairly fast despite rising prices and slowing population growth. That reflects increasing demand for American-like diets rich in animal products and processed foods (especially in China). That increasing demand is not going to slow down unless Asia's economic growth slows down, and I don't want that any more than I expect Ghosh does.

2) Ghosh discusses coarse grains but omits oil seed. The elephant in the room--which is closely connected to coarse grain markets--is soybeans. Soybean production is a big source of growth in staple food production and Asia is sucking it up, big time.

3) Yes, ethanol is a big deal. But that doesn't mean income growth in Asia isn't a big factor too.

4) Speculation has nothing to do with it. If speculation were a driving force, we would see inventory declines. Speculation can only cause prices to spike if it also causes inventories to accumulate. So whatever the contributions of the various factors, they are fundamental, not speculative. I've beat this horse many times, as have others who really know their stuff (Paul Krugman, Jim Hamilton at UCSD, Brian Wright at UC Berkeley, immediately come to mind).

I'm a bit concerned about they way Ghosh presents her data on consumption growth. First, by aggregating across decades and countries consumption is mostly inseparable from production. She shows growth rates for each in a series of decades, and the trend looks downward. That's basically because production growth has been approximately linear, so growth rates have declined as the baseline level production (the denominator) has grown larger. What's ominous is that bit of an increase in the recent decade: that's not production picking up but inventories getting drawn down, hence the price spike.

One thing I find a little strange is an apparent defensiveness on the part of some Asians about Asian demand growth. I, for one, don't blame them for their growth. Rather, I'm concerned that other poor nations (especially some African countries) are not growing as fast, and that many even in relatively rich and relatively growing countries seem to be left behind. We should worry about income inequality, especially in an environment with high and rising prices of food staples.

Friday, August 5, 2011

Stocks are a Really Good Deal

David Leonhardt says stocks are still expensive.

Brad Delong says buy equities!

Two super smart, super educated guys. Who's right?

Brad compares the price to earnings ratio of stocks to the interest rate on treasury bills. David Leonhard compares the price to earnings ratio to its historical average (albeit before the other day's crash).

I'm with Brad Delong. The problem with David's analysis is that he's forgetting week one of econ 101: opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of a dollar invested in the stock market is a dollar not invested in something else. The benchmark alternative is a long-run treasury. Brad points out that the rate on that is just dismal, less than today's dividend yield on stocks and far less than earnings.

David's mistake is a common one. I see the same mistake when looking at home prices (the price to rent ratio relative to its historical average, not relative to interest rates or building costs). It is important to take interest rates into account as well.

Brad Delong does it right by comparing the PE ratio to a proxy for the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate. Unfortunately it's a bit of work to develop a long history for long-term inflation-adjusted rates. If we had that rate we could develop a decent pricing index for stocks by multiplying a long-term real interest rate by the usual PE ratio (say, Robert Shilller's version, with earnings taken as the average of the past 10 years). When that index gets much above 1, stocks are probably a bad deal. When the index gets well below 1, stocks should look like a good deal.

Since I don't have a long-term real interest rate, but I can easily download a long history of 10 year nominal rates from FRED, here I'll create a second-best pricing index equal to the nominal rate multiplied by Shiller's PE ratio (available here). What you get is the following index:

The red line is drawn at the historical average. Note that this index ends in July, well before the recent crash. Also note that because I'm using a nominal rate rather than a real rate, stocks are probably a decent buy up to an index value that's a bit higher than one.

After yesterday's crash, which brought down interest rates and stock market prices, the index is probably close to 0.5.

Stocks look cheap to me.

Brad Delong says buy equities!

Two super smart, super educated guys. Who's right?

Brad compares the price to earnings ratio of stocks to the interest rate on treasury bills. David Leonhard compares the price to earnings ratio to its historical average (albeit before the other day's crash).

I'm with Brad Delong. The problem with David's analysis is that he's forgetting week one of econ 101: opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of a dollar invested in the stock market is a dollar not invested in something else. The benchmark alternative is a long-run treasury. Brad points out that the rate on that is just dismal, less than today's dividend yield on stocks and far less than earnings.

David's mistake is a common one. I see the same mistake when looking at home prices (the price to rent ratio relative to its historical average, not relative to interest rates or building costs). It is important to take interest rates into account as well.

Brad Delong does it right by comparing the PE ratio to a proxy for the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate. Unfortunately it's a bit of work to develop a long history for long-term inflation-adjusted rates. If we had that rate we could develop a decent pricing index for stocks by multiplying a long-term real interest rate by the usual PE ratio (say, Robert Shilller's version, with earnings taken as the average of the past 10 years). When that index gets much above 1, stocks are probably a bad deal. When the index gets well below 1, stocks should look like a good deal.

Since I don't have a long-term real interest rate, but I can easily download a long history of 10 year nominal rates from FRED, here I'll create a second-best pricing index equal to the nominal rate multiplied by Shiller's PE ratio (available here). What you get is the following index:

The red line is drawn at the historical average. Note that this index ends in July, well before the recent crash. Also note that because I'm using a nominal rate rather than a real rate, stocks are probably a decent buy up to an index value that's a bit higher than one.

After yesterday's crash, which brought down interest rates and stock market prices, the index is probably close to 0.5.

Stocks look cheap to me.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Marc Bellemare

Another triangle blogger.

I've been meaning to add Marc Bellemare to my blogroll and just got around to it. Marc is at Duke and shares a lot of my interests, with a bit more of a development focus. He gave a seminar here at NCSU awhile back and will probably give another one sometime soon.

He also just won best AJAE article of the year (AJAE is the top journal in agricultural economics).

Anyway, I recently learned about his blog via an email correspondence. Check it out! It looks like he'll be posting way more frequently than I do.

I've been meaning to add Marc Bellemare to my blogroll and just got around to it. Marc is at Duke and shares a lot of my interests, with a bit more of a development focus. He gave a seminar here at NCSU awhile back and will probably give another one sometime soon.

He also just won best AJAE article of the year (AJAE is the top journal in agricultural economics).

Anyway, I recently learned about his blog via an email correspondence. Check it out! It looks like he'll be posting way more frequently than I do.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Is Commodity Price Volatility Good or Bad? Wrong Question.

There's been a lot of discussion about food commodity price volatility and what governments and NGOs like the World Bank should do about it.

In principle, I don't see the question of price volatility as fundamentally different from a question about price levels. Sellers obviously like higher prices and buyers obviously like lower prices. But there is nothing about prices themselves that tell us whether the price is right. Instead, economists ask questions about how the market is functioning. Are there any externalities or other kinds of market imperfections that would cause the price level to be different from what would be if there were no imperfections?

Perhaps less abstractly, we might simply ask questions about what makes prices what they are, and whether some artificial force is keeping prices from their natural equilibrium.

The same goes for price volatility. When someone asks whether price volatility is good or bad--or worse, assumes it's bad and prescribes a policy to control it--my knee-jerk response is that it's the wrong question. We first need to ask why prices are volatile; and, especially, are there some big market imperfections that are causing prices to be more volatile that they would be if markets were functioning well. We simply cannot know whether prices volatility is good or bad without knowing what's causing the volatility.

Furthermore, even if some kind of imperfection is causing prices to be too volatile, we can't think cogently about reasonable policy options without knowing something about the fundamental cause. So, asking questions about whether price volatility is good or bad really misses the point.

Here are two quick examples:

First, suppose price volatility is coming about because we've had an unusual stint of bad weather, drawing down inventories. When inventories are low, just a little bit of news can cause prices to change a lot, since we don't have much of a buffer. In this situation there really isn't a whole lot that can be done that would improve things. Indeed, most anything one tries to do is likely to make matters worse and possibly make prices even more volatile. Put another way, the rise in price and volatility is a symptom of the market trying to deal with the adverse situation.

Second, suppose price volatility has come about from a major exporter suddenly and unexpectedly placed quota on the volume of its exports. This would cause world prices to rise, inventories to decline, and volatility to increase, much like a stint of bad weather shocks. Obviously this would be bad from the vantage point of total economic welfare: the world would be willing to pay more for a unit of the commodity than producers in the exporting country would be willing to sell it. There are mutual benefits from more trade and so we have a clear market imperfection. The best policy response would be to convince the exporting country to drop its quota.

Yes, I realize the real world is more complicated. And there might be some reasonable "second best" policy options for a real-world problem like an export quota that a country just won't drop.

I'm not saying I've got the answers to these more complex situations. All I'm saying is that one cannot begin to deal with the situation without first identifying the source of the problem. Because the prices themselves don't tell us what that problem is.

In principle, I don't see the question of price volatility as fundamentally different from a question about price levels. Sellers obviously like higher prices and buyers obviously like lower prices. But there is nothing about prices themselves that tell us whether the price is right. Instead, economists ask questions about how the market is functioning. Are there any externalities or other kinds of market imperfections that would cause the price level to be different from what would be if there were no imperfections?

Perhaps less abstractly, we might simply ask questions about what makes prices what they are, and whether some artificial force is keeping prices from their natural equilibrium.

The same goes for price volatility. When someone asks whether price volatility is good or bad--or worse, assumes it's bad and prescribes a policy to control it--my knee-jerk response is that it's the wrong question. We first need to ask why prices are volatile; and, especially, are there some big market imperfections that are causing prices to be more volatile that they would be if markets were functioning well. We simply cannot know whether prices volatility is good or bad without knowing what's causing the volatility.

Furthermore, even if some kind of imperfection is causing prices to be too volatile, we can't think cogently about reasonable policy options without knowing something about the fundamental cause. So, asking questions about whether price volatility is good or bad really misses the point.

Here are two quick examples:

First, suppose price volatility is coming about because we've had an unusual stint of bad weather, drawing down inventories. When inventories are low, just a little bit of news can cause prices to change a lot, since we don't have much of a buffer. In this situation there really isn't a whole lot that can be done that would improve things. Indeed, most anything one tries to do is likely to make matters worse and possibly make prices even more volatile. Put another way, the rise in price and volatility is a symptom of the market trying to deal with the adverse situation.

Second, suppose price volatility has come about from a major exporter suddenly and unexpectedly placed quota on the volume of its exports. This would cause world prices to rise, inventories to decline, and volatility to increase, much like a stint of bad weather shocks. Obviously this would be bad from the vantage point of total economic welfare: the world would be willing to pay more for a unit of the commodity than producers in the exporting country would be willing to sell it. There are mutual benefits from more trade and so we have a clear market imperfection. The best policy response would be to convince the exporting country to drop its quota.

Yes, I realize the real world is more complicated. And there might be some reasonable "second best" policy options for a real-world problem like an export quota that a country just won't drop.

I'm not saying I've got the answers to these more complex situations. All I'm saying is that one cannot begin to deal with the situation without first identifying the source of the problem. Because the prices themselves don't tell us what that problem is.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Why the Deficit Should Be Bigger

Today the government can borrow money, amortized over 10 years, at just 2.6%.

What would you do if you could borrow a lot money at 2.6% amortized over 10 years? Would you use it to finance a college education? Would you buy a home or larger home? Buy a house and rent it out for, 2-3 times your monthly interest payment? Start a business? Most of us, I think, could find some investment that would pay more than the 2.6% borrowing cost.

But here's the thing: Because the government represents all of us, its expenditures on education, infrastructure and research ultimately benefit all of us, it can (and has) obtained returns far greater than we can earn as individuals. And that doesn't even count Keynesian multiplier effects, which amplify the benefits tremendously.

This should be a no-brainer even if, despite all the evidence, you're an anti-Keynesian. If you're an anti-Keynesian and think that hyperinflation is just around the corner, then this is a truly stupendous deal, since in real terms that nominal 2.6% rate is actually some big negative number. It's almost free money. What's the problem?

If you have actually followed the arguments, know the history, and have seen at the data (1937, the Great Depression, Japan and all that) and realize expansionary fiscal policy really is expansionary when an economy is as depressed as ours, then there is the added bonus of a significant multiplier on top of the added long-run growth.

So deficits should be bigger. Now, in the middle of a deeply depressed economy, is not the time to pay down deficits. That time will come, when interest rates are higher, we don't have so much excess capacity and so much unemployment. At such a time increased government spending would in fact displace private investment and drive interest rates up. But that time is not today and won't be in the next two or three years, at least.

I'm saddened and frustrated by the massive and needless suffering taking place. And worse, by the evening news and our fear-driven leaders who can't even get the basic econ 101 right, and thereby strive to deepen and widen the sea of needless misery.

Update: I realize all this has been said before, perhaps more eloquently, by many others. Just adding another small voice in the wilderness....

What would you do if you could borrow a lot money at 2.6% amortized over 10 years? Would you use it to finance a college education? Would you buy a home or larger home? Buy a house and rent it out for, 2-3 times your monthly interest payment? Start a business? Most of us, I think, could find some investment that would pay more than the 2.6% borrowing cost.

But here's the thing: Because the government represents all of us, its expenditures on education, infrastructure and research ultimately benefit all of us, it can (and has) obtained returns far greater than we can earn as individuals. And that doesn't even count Keynesian multiplier effects, which amplify the benefits tremendously.

This should be a no-brainer even if, despite all the evidence, you're an anti-Keynesian. If you're an anti-Keynesian and think that hyperinflation is just around the corner, then this is a truly stupendous deal, since in real terms that nominal 2.6% rate is actually some big negative number. It's almost free money. What's the problem?

If you have actually followed the arguments, know the history, and have seen at the data (1937, the Great Depression, Japan and all that) and realize expansionary fiscal policy really is expansionary when an economy is as depressed as ours, then there is the added bonus of a significant multiplier on top of the added long-run growth.

So deficits should be bigger. Now, in the middle of a deeply depressed economy, is not the time to pay down deficits. That time will come, when interest rates are higher, we don't have so much excess capacity and so much unemployment. At such a time increased government spending would in fact displace private investment and drive interest rates up. But that time is not today and won't be in the next two or three years, at least.

I'm saddened and frustrated by the massive and needless suffering taking place. And worse, by the evening news and our fear-driven leaders who can't even get the basic econ 101 right, and thereby strive to deepen and widen the sea of needless misery.

Update: I realize all this has been said before, perhaps more eloquently, by many others. Just adding another small voice in the wilderness....

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

It's been a long haul, but my coauthor Wolfram Schlenker and I have finally published our article with the title of this blog post in th...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...