At the ASSA meetings next month I'm going to present some new research wherein we (Wolfram Schlenker, Jon Eyer and myself), incorporate vapor pressure deficit (VPD) into earlier regressions linking crop yields to weather. Vapor pressure deficit, a close cousin to relative humidity, has a linear relationship with evaporation, and is a key input in many crop models. For this meeting we're only presenting evidence on Illinois, which has been our testing ground for fine-scale data development.

If you haven't been following, I've written a lot about the strong and robust association between extreme heat and crop yields. This puzzles some crop scientists who focus on soil moisture and precipitation as the key impediments to higher yields. But in comparison to any precipitation or soil moisture variable we've constructed, extreme heat, measured as degree days above 29C, is a far better predictor of yield. And the underlying relationship is similar across widely varying climates and whether identified over the cross section (comparing average yields with average climates over locations) or the time series (comparing yields over time in a fixed location with different weather outcomes). Such a robust and pervasive pattern in observational data is extremely rare.

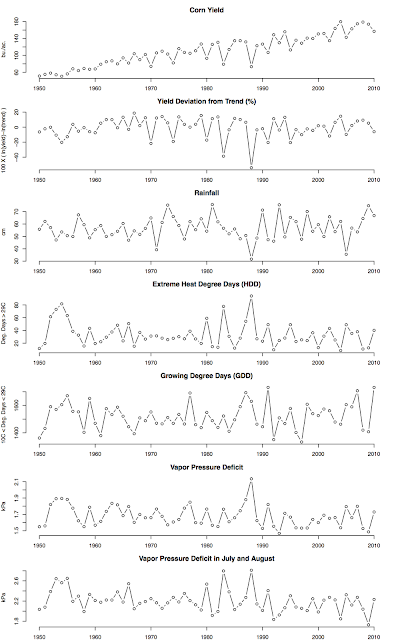

Most of the hard work is in constructing fine-scale measures VPD and degree day measures, including our measure of extreme heat. Since these measures are nonlinear in temperature, accurate measurement requires daily measures of minimums and maximums on a fine geographic scale that is matched with the locations where crops are grown. This involves tedious cleaning of weather station data and a combination of statistical techniques and a climate model to interpolate weather outcomes between weather stations. Once we estimate VDP, precipitation and temperature measures on a fine scale, we then aggregate, weighting each fine-scale grid by the crop area. State-level plots over time are shown below (click for a larger view).

There are two interesting things about the VPD measure we construct. First, average VPD for July and August is closely associated with our best-fitting extreme heat measure, at least in Illinois. Second, adding VPD for the season and VPD for July and August to our standard regression greatly improves prediction. Using just five variables, these two plus growing degree days (degree days between 10C and 29C), extreme heat degree days (degree days above 29C) and precipitation, we can explain over 70 percent of the variance of Illinois yields, excluding the upward trend. That's better than USDA's August and September forecasts, which are based on field-level samples and farmer interviews. The model can explain almost half the difference between the August forecast and the final yield for Illinois. Here's a picture of the fit:

When we simulate these variables for future climates the outlook isn't much different from our earlier predictions: really bad. But there is somewhat greater uncertainty around projected impacts, drawing mainly from interaction effects with precipitation after we account for VPD. And since VPD, like extreme heat, is sensitive to the distribution of temperatures, things may not turn out as bad if warming occurs mostly in cooler months, or if lows increase more than maximums do. Of course, if maximums increase more than minimums do, things could be a lot worse. My sense from the climate scientists is that there is a lot more uncertainty about these more subtle features of climate change.

Also, these statistical models cannot realistically account CO2 effects, because CO2 has increased slowly over time and so cannot be separated from technological change. At this point, CO2 effects for corn (a so-called C4 crop) are expected to be modest, but may aid heat tolerance.

I mainly see this work as another small step toward bridging deterministic crop models and statistical models. A better ability to predict yields with weather should also aid estimation of economic phenomenon, since year-to-year weather variation is nice exogenous variable that can serve as an instrument in supply and demand estimation. There may also be crop insurance applications.

Friday, December 30, 2011

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

The Problem with ECB Lending

The other day Floyd Norris deftly explained the delicate situation with the Euro and the debt crises facing Italy, Spain, and other European nations, and how the ECB is now, finally, taking concrete steps to deal with the problem. But I'm worried that what the ECB is doing won't be enough. I haven't seen much about this, perhaps because I've been looking in the wrong places, so I thought I'd throw this out there.

The situation is fragile and markets are volatile mainly because the outcome is expectations dependent. If financial markets believe countries like Italy and France will surely honor their debts, interest rates will fall and the debt burden will be manageable. But if financial markets believe these countries will not honor their debts, interest rates will rise to a point that their debts will become impossible to pay back, thereby forcing default. In other words, expectations, good or bad, will be self-fulfilling. Global markets are volatile because it's not clear where this expectations game will land.

It's very much like an impending traditional bank run: If depositors are confident no other depositor will withdraw their funds, no one will withdraw; but if depositors believe a critical number of depositors will withdraw, it will collapse the bank, and everyone should rush to withdraw as soon as possible.

So, how do we deal with bank runs? In the US bank runs of the traditional variety hardly ever occur, mainly because deposits are guaranteed by the government (FDIC). Banks can also deal with short-run liquidity problems by borrowing from the Fed at the discount rate. Both mechanisms are probably helpful, but the FDIC guarantee is the critical feature. The discount window does not guarantee deposits or bank survival in the event everyone withdraws, so it doesn't solve the expectations problem.

And this brings me to the problem with the ECB's lending program.

One clear solution would be to have the ECB print Euros and buy bonds from these frgile countries. If purchases were vigorous, this would be almost like FDIC insurance and push expectations and the ultimate outcome to the positive side. But the ECB refuses to do this, claiming it is beyond their mandate. And because Germany and other countries strenuously object to ECB bond purchases, it's a political non-starter, at least for now.

Instead, the ECB is lending liberally to European banks at low interest rates, much like banks in the US using the Fed's discount window. The idea is that banks will then buy their own country's bonds, pushing rates down, much as if the ECB were buying the bonds directly.

I fear the problem with this approach is that it doesn't necessarily solve the expectations problem. The banks may borrow cheaply from the ECB, but unless all the banks believe all the other banks will also buy domestic bonds, it's not in their interest to buy them either. Indeed, they may find it safer to buy German bunds, or maybe even US treasuries. Or maybe they'll do like our banks and just hold the cash as reserves.

It's a bit like trying to stop a bank run by printing money and giving it to depositors, hoping that, having cash in hand, they'll be less interested in withdrawing their deposits from the bank. But people weren't tempted to withdraw funds because they needed the cash; they were tempted to withdraw because they were worried others would withdraw, thereby causing the bank to collapse.

Similarly, I fear the ECB's latest efforts, though significant and a step in the right direction, will not be enough.

The situation is fragile and markets are volatile mainly because the outcome is expectations dependent. If financial markets believe countries like Italy and France will surely honor their debts, interest rates will fall and the debt burden will be manageable. But if financial markets believe these countries will not honor their debts, interest rates will rise to a point that their debts will become impossible to pay back, thereby forcing default. In other words, expectations, good or bad, will be self-fulfilling. Global markets are volatile because it's not clear where this expectations game will land.

It's very much like an impending traditional bank run: If depositors are confident no other depositor will withdraw their funds, no one will withdraw; but if depositors believe a critical number of depositors will withdraw, it will collapse the bank, and everyone should rush to withdraw as soon as possible.

So, how do we deal with bank runs? In the US bank runs of the traditional variety hardly ever occur, mainly because deposits are guaranteed by the government (FDIC). Banks can also deal with short-run liquidity problems by borrowing from the Fed at the discount rate. Both mechanisms are probably helpful, but the FDIC guarantee is the critical feature. The discount window does not guarantee deposits or bank survival in the event everyone withdraws, so it doesn't solve the expectations problem.

And this brings me to the problem with the ECB's lending program.

One clear solution would be to have the ECB print Euros and buy bonds from these frgile countries. If purchases were vigorous, this would be almost like FDIC insurance and push expectations and the ultimate outcome to the positive side. But the ECB refuses to do this, claiming it is beyond their mandate. And because Germany and other countries strenuously object to ECB bond purchases, it's a political non-starter, at least for now.

Instead, the ECB is lending liberally to European banks at low interest rates, much like banks in the US using the Fed's discount window. The idea is that banks will then buy their own country's bonds, pushing rates down, much as if the ECB were buying the bonds directly.

I fear the problem with this approach is that it doesn't necessarily solve the expectations problem. The banks may borrow cheaply from the ECB, but unless all the banks believe all the other banks will also buy domestic bonds, it's not in their interest to buy them either. Indeed, they may find it safer to buy German bunds, or maybe even US treasuries. Or maybe they'll do like our banks and just hold the cash as reserves.

It's a bit like trying to stop a bank run by printing money and giving it to depositors, hoping that, having cash in hand, they'll be less interested in withdrawing their deposits from the bank. But people weren't tempted to withdraw funds because they needed the cash; they were tempted to withdraw because they were worried others would withdraw, thereby causing the bank to collapse.

Similarly, I fear the ECB's latest efforts, though significant and a step in the right direction, will not be enough.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Health Care and Tiebout Sorting: Someone Please Look at Massachusetts

Very thin posting these days because, well because I've been trying to get real papers out and preparing for the upcoming ASSA meetings in Chicago. I'll try to post something about at least one of my presentations there in the next few days.

Anyway, amid debate about Obamacare, Romneycare, and how Newt has felt about Romneycare both past and present, I think it would be interesting if someone were to take a closer look at how Romney's health care bill in Massachusetts has affected migration to and from the state, as well as real estate prices, wages and unemployment. This would seem to be a perfect application of modern empirical sorting models. The change in the law in Massachusetts would seem be a reasonably viable, if imperfect, natural experiment for the Northeastern corridor.

It's not my area and there's no chance I'll get to anything like this in the next decade. But if no one is doing this right now, someone should, preferably before the general election gets underway next year.

Anyway, amid debate about Obamacare, Romneycare, and how Newt has felt about Romneycare both past and present, I think it would be interesting if someone were to take a closer look at how Romney's health care bill in Massachusetts has affected migration to and from the state, as well as real estate prices, wages and unemployment. This would seem to be a perfect application of modern empirical sorting models. The change in the law in Massachusetts would seem be a reasonably viable, if imperfect, natural experiment for the Northeastern corridor.

It's not my area and there's no chance I'll get to anything like this in the next decade. But if no one is doing this right now, someone should, preferably before the general election gets underway next year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

It's been a long haul, but my coauthor Wolfram Schlenker and I have finally published our article with the title of this blog post in th...

-

This morning's slides. I believe slides with audio of the presentation will eventually be posted here . Open publication - Free pub...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...