At the ASSA meetings next month I'm going to present some new research wherein we (Wolfram Schlenker, Jon Eyer and myself), incorporate vapor pressure deficit (VPD) into earlier regressions linking crop yields to weather. Vapor pressure deficit, a close cousin to relative humidity, has a linear relationship with evaporation, and is a key input in many crop models. For this meeting we're only presenting evidence on Illinois, which has been our testing ground for fine-scale data development.

If you haven't been following, I've written a lot about the strong and robust association between extreme heat and crop yields. This puzzles some crop scientists who focus on soil moisture and precipitation as the key impediments to higher yields. But in comparison to any precipitation or soil moisture variable we've constructed, extreme heat, measured as degree days above 29C, is a far better predictor of yield. And the underlying relationship is similar across widely varying climates and whether identified over the cross section (comparing average yields with average climates over locations) or the time series (comparing yields over time in a fixed location with different weather outcomes). Such a robust and pervasive pattern in observational data is extremely rare.

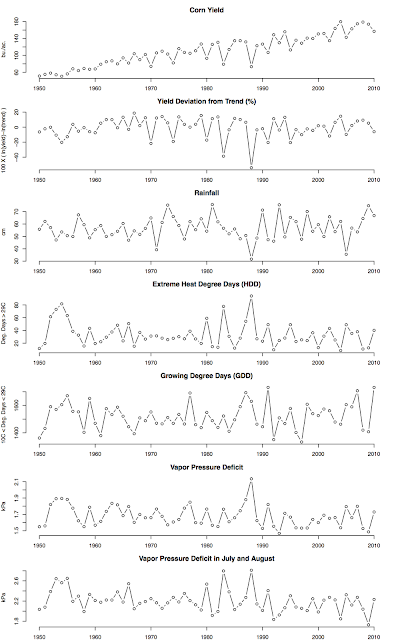

Most of the hard work is in constructing fine-scale measures VPD and degree day measures, including our measure of extreme heat. Since these measures are nonlinear in temperature, accurate measurement requires daily measures of minimums and maximums on a fine geographic scale that is matched with the locations where crops are grown. This involves tedious cleaning of weather station data and a combination of statistical techniques and a climate model to interpolate weather outcomes between weather stations. Once we estimate VDP, precipitation and temperature measures on a fine scale, we then aggregate, weighting each fine-scale grid by the crop area. State-level plots over time are shown below (click for a larger view).

There are two interesting things about the VPD measure we construct. First, average VPD for July and August is closely associated with our best-fitting extreme heat measure, at least in Illinois. Second, adding VPD for the season and VPD for July and August to our standard regression greatly improves prediction. Using just five variables, these two plus growing degree days (degree days between 10C and 29C), extreme heat degree days (degree days above 29C) and precipitation, we can explain over 70 percent of the variance of Illinois yields, excluding the upward trend. That's better than USDA's August and September forecasts, which are based on field-level samples and farmer interviews. The model can explain almost half the difference between the August forecast and the final yield for Illinois. Here's a picture of the fit:

When we simulate these variables for future climates the outlook isn't much different from our earlier predictions: really bad. But there is somewhat greater uncertainty around projected impacts, drawing mainly from interaction effects with precipitation after we account for VPD. And since VPD, like extreme heat, is sensitive to the distribution of temperatures, things may not turn out as bad if warming occurs mostly in cooler months, or if lows increase more than maximums do. Of course, if maximums increase more than minimums do, things could be a lot worse. My sense from the climate scientists is that there is a lot more uncertainty about these more subtle features of climate change.

Also, these statistical models cannot realistically account CO2 effects, because CO2 has increased slowly over time and so cannot be separated from technological change. At this point, CO2 effects for corn (a so-called C4 crop) are expected to be modest, but may aid heat tolerance.

I mainly see this work as another small step toward bridging deterministic crop models and statistical models. A better ability to predict yields with weather should also aid estimation of economic phenomenon, since year-to-year weather variation is nice exogenous variable that can serve as an instrument in supply and demand estimation. There may also be crop insurance applications.

Friday, December 30, 2011

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

The Problem with ECB Lending

The other day Floyd Norris deftly explained the delicate situation with the Euro and the debt crises facing Italy, Spain, and other European nations, and how the ECB is now, finally, taking concrete steps to deal with the problem. But I'm worried that what the ECB is doing won't be enough. I haven't seen much about this, perhaps because I've been looking in the wrong places, so I thought I'd throw this out there.

The situation is fragile and markets are volatile mainly because the outcome is expectations dependent. If financial markets believe countries like Italy and France will surely honor their debts, interest rates will fall and the debt burden will be manageable. But if financial markets believe these countries will not honor their debts, interest rates will rise to a point that their debts will become impossible to pay back, thereby forcing default. In other words, expectations, good or bad, will be self-fulfilling. Global markets are volatile because it's not clear where this expectations game will land.

It's very much like an impending traditional bank run: If depositors are confident no other depositor will withdraw their funds, no one will withdraw; but if depositors believe a critical number of depositors will withdraw, it will collapse the bank, and everyone should rush to withdraw as soon as possible.

So, how do we deal with bank runs? In the US bank runs of the traditional variety hardly ever occur, mainly because deposits are guaranteed by the government (FDIC). Banks can also deal with short-run liquidity problems by borrowing from the Fed at the discount rate. Both mechanisms are probably helpful, but the FDIC guarantee is the critical feature. The discount window does not guarantee deposits or bank survival in the event everyone withdraws, so it doesn't solve the expectations problem.

And this brings me to the problem with the ECB's lending program.

One clear solution would be to have the ECB print Euros and buy bonds from these frgile countries. If purchases were vigorous, this would be almost like FDIC insurance and push expectations and the ultimate outcome to the positive side. But the ECB refuses to do this, claiming it is beyond their mandate. And because Germany and other countries strenuously object to ECB bond purchases, it's a political non-starter, at least for now.

Instead, the ECB is lending liberally to European banks at low interest rates, much like banks in the US using the Fed's discount window. The idea is that banks will then buy their own country's bonds, pushing rates down, much as if the ECB were buying the bonds directly.

I fear the problem with this approach is that it doesn't necessarily solve the expectations problem. The banks may borrow cheaply from the ECB, but unless all the banks believe all the other banks will also buy domestic bonds, it's not in their interest to buy them either. Indeed, they may find it safer to buy German bunds, or maybe even US treasuries. Or maybe they'll do like our banks and just hold the cash as reserves.

It's a bit like trying to stop a bank run by printing money and giving it to depositors, hoping that, having cash in hand, they'll be less interested in withdrawing their deposits from the bank. But people weren't tempted to withdraw funds because they needed the cash; they were tempted to withdraw because they were worried others would withdraw, thereby causing the bank to collapse.

Similarly, I fear the ECB's latest efforts, though significant and a step in the right direction, will not be enough.

The situation is fragile and markets are volatile mainly because the outcome is expectations dependent. If financial markets believe countries like Italy and France will surely honor their debts, interest rates will fall and the debt burden will be manageable. But if financial markets believe these countries will not honor their debts, interest rates will rise to a point that their debts will become impossible to pay back, thereby forcing default. In other words, expectations, good or bad, will be self-fulfilling. Global markets are volatile because it's not clear where this expectations game will land.

It's very much like an impending traditional bank run: If depositors are confident no other depositor will withdraw their funds, no one will withdraw; but if depositors believe a critical number of depositors will withdraw, it will collapse the bank, and everyone should rush to withdraw as soon as possible.

So, how do we deal with bank runs? In the US bank runs of the traditional variety hardly ever occur, mainly because deposits are guaranteed by the government (FDIC). Banks can also deal with short-run liquidity problems by borrowing from the Fed at the discount rate. Both mechanisms are probably helpful, but the FDIC guarantee is the critical feature. The discount window does not guarantee deposits or bank survival in the event everyone withdraws, so it doesn't solve the expectations problem.

And this brings me to the problem with the ECB's lending program.

One clear solution would be to have the ECB print Euros and buy bonds from these frgile countries. If purchases were vigorous, this would be almost like FDIC insurance and push expectations and the ultimate outcome to the positive side. But the ECB refuses to do this, claiming it is beyond their mandate. And because Germany and other countries strenuously object to ECB bond purchases, it's a political non-starter, at least for now.

Instead, the ECB is lending liberally to European banks at low interest rates, much like banks in the US using the Fed's discount window. The idea is that banks will then buy their own country's bonds, pushing rates down, much as if the ECB were buying the bonds directly.

I fear the problem with this approach is that it doesn't necessarily solve the expectations problem. The banks may borrow cheaply from the ECB, but unless all the banks believe all the other banks will also buy domestic bonds, it's not in their interest to buy them either. Indeed, they may find it safer to buy German bunds, or maybe even US treasuries. Or maybe they'll do like our banks and just hold the cash as reserves.

It's a bit like trying to stop a bank run by printing money and giving it to depositors, hoping that, having cash in hand, they'll be less interested in withdrawing their deposits from the bank. But people weren't tempted to withdraw funds because they needed the cash; they were tempted to withdraw because they were worried others would withdraw, thereby causing the bank to collapse.

Similarly, I fear the ECB's latest efforts, though significant and a step in the right direction, will not be enough.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Health Care and Tiebout Sorting: Someone Please Look at Massachusetts

Very thin posting these days because, well because I've been trying to get real papers out and preparing for the upcoming ASSA meetings in Chicago. I'll try to post something about at least one of my presentations there in the next few days.

Anyway, amid debate about Obamacare, Romneycare, and how Newt has felt about Romneycare both past and present, I think it would be interesting if someone were to take a closer look at how Romney's health care bill in Massachusetts has affected migration to and from the state, as well as real estate prices, wages and unemployment. This would seem to be a perfect application of modern empirical sorting models. The change in the law in Massachusetts would seem be a reasonably viable, if imperfect, natural experiment for the Northeastern corridor.

It's not my area and there's no chance I'll get to anything like this in the next decade. But if no one is doing this right now, someone should, preferably before the general election gets underway next year.

Anyway, amid debate about Obamacare, Romneycare, and how Newt has felt about Romneycare both past and present, I think it would be interesting if someone were to take a closer look at how Romney's health care bill in Massachusetts has affected migration to and from the state, as well as real estate prices, wages and unemployment. This would seem to be a perfect application of modern empirical sorting models. The change in the law in Massachusetts would seem be a reasonably viable, if imperfect, natural experiment for the Northeastern corridor.

It's not my area and there's no chance I'll get to anything like this in the next decade. But if no one is doing this right now, someone should, preferably before the general election gets underway next year.

Monday, November 21, 2011

On Futures Markets Convergence to Spot Prices

This is a bit wonkish. It also contains a lot of preliminary thinking on my part, so caveat emptor. If I'm wrong about any of this, I'll owe up to it sooner or later, and hopefully sooner.

Futures markets are super useful things. They allow a farmer to lock in a selling price for his grain before incurring all his production expenses, thereby limiting his risk. And they allow an ethanol plant manager to lock in her buying price for grain before scheduling a delivery of fuel, thereby limiting the ethanol plant's risk. Thus, futures markets are generally wonderful things, allowing people to coordinate and plan production and consumption a little better over time, and thereby improving the efficiency of markets.

In recent years there has been a big inflow of money from Wall Street into commodity futures. Basically, there is a ton of money out there looking for someplace to hide in the crazy, fearful world of international financial markets. Commodities have been a pretty good bet of late, so agriculture and other areas are receiving more than their share of the giant pool of money. As that influx occurred there has been some peculiar behavior in some futures markets, particularly in grains. Futures markets, which trade on gains to be delivered at some future date, have not been converging to spot prices--the price one has to pay for grain at a particular moment in time.

To economists, this is a strange phenomenon. Non-convergence looks like an arbitrage opportunity--like money lying on the table that no one is picking up. If the futures price is above the spot price just before before delivery, then sellers should sell on the futures market and buyers should buy on the spot market, driving the prices toward each other. If the futures price is below the spot price, the opposite should occur. So spot prices and futures prices should always converge on the delivery date of the futures contract.

But they haven't always.

A very nice new paper by Philip Garcia, Scott Irwin and Aaron Smith seeks to explain why futures prices have not been converging to spot prices, especially of late, and especially in grain markets. (NB: Scott Irwin recently sent me a copy--I haven't been paying much attention to this until now.)

I'm just starting to get my head wrapped around this paper. While I think they nail the jist of things, it seems to me they may be making the situation a bit more complicated than it needs to be.

There are a few key issues here.

First, there isn't a futures market for every day and minute of the year. Futures contracts are usually only written for certain months of the year (in grains, usually 4 to 6 of the 12 months of the year). And formal trading usually stops a few days to a couple weeks before [the last day] delivery is promised.

Second, in grain markets, a futures delivery isn't for grain, but for a ticket that the buyer can redeem for grain from a certified and registered "regular" trader, usually a big conglomerate like Cargill or ADM, that has the proven facility to store grain and honor deliveries. The buyer isn't required to take delivery, but if s/he doesn't, then s/he must pay a storage fee to the regular. So buying a future isn't really buying grain for delivery; it's buying an option to take delivery for some grain. [The fact that there is flexibility in the timing of delivery is key.]

Now suppose you're bullish on grains--you think prices are going to be going up over time. There are two ways you can bet on this premonition: (1) you can buy grain and store it; (2) you can buy futures. If you're Cargill you might choose option (1), since you have a comparative advantage in storage facilities. If you're a Wall Street trader you'll choose option (2)--you've got no direct use for grain or any place to feasibly store it.

Okay, so suppose you're a Wall Street trader and you've bought grain on the future's market. But spot prices turn out less than the price of your futures contract on delivery. Still, you're fairly bullish on commodity prices going forward: you think prices will go up eventually. You've got two options: (A) take delivery and immediately sell your grain at the spot price, absorb your loss, and buy another futures contract for the next delivery date; (B) keep your futures contract and pay a storage fee to the regular associated with your ticket. For (B), you basically let the regular store your grain for you.

In this situation it's not so surprising (to me, anyway) that option (B) might make a lot of sense to outside investors. Perhaps the outside investor thinks prices could spike soon, well before the next delivery date. Perhaps the futures price for the next contract is considerably higher than the current spot price.

If enough outside investors feel this way, and taken together are more inclined to store grain than regulars like Cargill or ADM, we can have futures prices that don't converge to spot prices--the prices at which Cargill and ADM are willing to sell grain at the moment. After all, outside investors are looking to grains to spread their risk to something less aligned to their predominant position--stocks, bonds, etc. They are going to be much less concerned about risk in agricultural markets than major agricultural players, and thus more comfortable taking long positions (ie., buying futures/storing grains).

The more I think about this the more it seems strange to me that futures markets converge as closely as they do to spot markets. Convergence, it seems, requires that only the regulars (Cargill, ADM, etc.) are indifferent to selling short and storing or buying long. When they're not the marginal traders, we can have non-convergence.

None of this implies markets are irrational or imperfect, except that there isn't a separate futures contract for every moment. (But I do not mean to suggest that markets can be irrational and/or imperfect in other situations...)

The punchline is that, by raising the storage fee associated with not taking delivery on the futures contract, outside investors will be less inclined to let regulars do their storing for them. They will instead absorb their losses and reinvest in the next futures contract. Regulars will once again be the marginal traders in both futures and spot market, and we'll have convergence of futures prices to spot prices.

It's not perfectly clear to me that higher storage fees are in broader social interest. But they might be. And the regulars certainly won't mind.

Futures markets are super useful things. They allow a farmer to lock in a selling price for his grain before incurring all his production expenses, thereby limiting his risk. And they allow an ethanol plant manager to lock in her buying price for grain before scheduling a delivery of fuel, thereby limiting the ethanol plant's risk. Thus, futures markets are generally wonderful things, allowing people to coordinate and plan production and consumption a little better over time, and thereby improving the efficiency of markets.

In recent years there has been a big inflow of money from Wall Street into commodity futures. Basically, there is a ton of money out there looking for someplace to hide in the crazy, fearful world of international financial markets. Commodities have been a pretty good bet of late, so agriculture and other areas are receiving more than their share of the giant pool of money. As that influx occurred there has been some peculiar behavior in some futures markets, particularly in grains. Futures markets, which trade on gains to be delivered at some future date, have not been converging to spot prices--the price one has to pay for grain at a particular moment in time.

To economists, this is a strange phenomenon. Non-convergence looks like an arbitrage opportunity--like money lying on the table that no one is picking up. If the futures price is above the spot price just before before delivery, then sellers should sell on the futures market and buyers should buy on the spot market, driving the prices toward each other. If the futures price is below the spot price, the opposite should occur. So spot prices and futures prices should always converge on the delivery date of the futures contract.

But they haven't always.

A very nice new paper by Philip Garcia, Scott Irwin and Aaron Smith seeks to explain why futures prices have not been converging to spot prices, especially of late, and especially in grain markets. (NB: Scott Irwin recently sent me a copy--I haven't been paying much attention to this until now.)

I'm just starting to get my head wrapped around this paper. While I think they nail the jist of things, it seems to me they may be making the situation a bit more complicated than it needs to be.

There are a few key issues here.

First, there isn't a futures market for every day and minute of the year. Futures contracts are usually only written for certain months of the year (in grains, usually 4 to 6 of the 12 months of the year). And formal trading usually stops a few days to a couple weeks before [the last day] delivery is promised.

Second, in grain markets, a futures delivery isn't for grain, but for a ticket that the buyer can redeem for grain from a certified and registered "regular" trader, usually a big conglomerate like Cargill or ADM, that has the proven facility to store grain and honor deliveries. The buyer isn't required to take delivery, but if s/he doesn't, then s/he must pay a storage fee to the regular. So buying a future isn't really buying grain for delivery; it's buying an option to take delivery for some grain. [The fact that there is flexibility in the timing of delivery is key.]

Now suppose you're bullish on grains--you think prices are going to be going up over time. There are two ways you can bet on this premonition: (1) you can buy grain and store it; (2) you can buy futures. If you're Cargill you might choose option (1), since you have a comparative advantage in storage facilities. If you're a Wall Street trader you'll choose option (2)--you've got no direct use for grain or any place to feasibly store it.

Okay, so suppose you're a Wall Street trader and you've bought grain on the future's market. But spot prices turn out less than the price of your futures contract on delivery. Still, you're fairly bullish on commodity prices going forward: you think prices will go up eventually. You've got two options: (A) take delivery and immediately sell your grain at the spot price, absorb your loss, and buy another futures contract for the next delivery date; (B) keep your futures contract and pay a storage fee to the regular associated with your ticket. For (B), you basically let the regular store your grain for you.

In this situation it's not so surprising (to me, anyway) that option (B) might make a lot of sense to outside investors. Perhaps the outside investor thinks prices could spike soon, well before the next delivery date. Perhaps the futures price for the next contract is considerably higher than the current spot price.

If enough outside investors feel this way, and taken together are more inclined to store grain than regulars like Cargill or ADM, we can have futures prices that don't converge to spot prices--the prices at which Cargill and ADM are willing to sell grain at the moment. After all, outside investors are looking to grains to spread their risk to something less aligned to their predominant position--stocks, bonds, etc. They are going to be much less concerned about risk in agricultural markets than major agricultural players, and thus more comfortable taking long positions (ie., buying futures/storing grains).

The more I think about this the more it seems strange to me that futures markets converge as closely as they do to spot markets. Convergence, it seems, requires that only the regulars (Cargill, ADM, etc.) are indifferent to selling short and storing or buying long. When they're not the marginal traders, we can have non-convergence.

None of this implies markets are irrational or imperfect, except that there isn't a separate futures contract for every moment. (But I do not mean to suggest that markets can be irrational and/or imperfect in other situations...)

The punchline is that, by raising the storage fee associated with not taking delivery on the futures contract, outside investors will be less inclined to let regulars do their storing for them. They will instead absorb their losses and reinvest in the next futures contract. Regulars will once again be the marginal traders in both futures and spot market, and we'll have convergence of futures prices to spot prices.

It's not perfectly clear to me that higher storage fees are in broader social interest. But they might be. And the regulars certainly won't mind.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Evidence-Based Macroeconomics, Firemen and Fires

The firemen came and put out the fire. They kept the fire from spreading further, but not before a number of homes burnt down. Now the townspeople are standing around the smoldering ruins, looking up at the firemen, and a scandalous rumor emerges: that the firemen started the fire.

Via Paul Krugman, here is a really wonderful talk by Chistina Romer on the effects of fiscal stimulus.

Her challenge is to convince people that the Obama administration's big stimulus was actually stimulative, even though, despite the stimulus, the economy is still in ruins. The challenge is that stimulus is like firemen: we only use it when disaster occurs.

It makes some important and powerful points about why people should believe fiscal stimulus is in fact stimulative. But perhaps even more than that, it's wonderful in its clarity about (a) how important empirical answers are, (b) how difficult it is to obtain empirical answers to big economic questions, and (c) that good empirical economics is often less about technique and about "shoe leather," as the former statistician David Freedman liked to say.

Also, it's just a fine example of good presentation: beautiful in its clarity of thought and persuasiveness.

Via Paul Krugman, here is a really wonderful talk by Chistina Romer on the effects of fiscal stimulus.

Her challenge is to convince people that the Obama administration's big stimulus was actually stimulative, even though, despite the stimulus, the economy is still in ruins. The challenge is that stimulus is like firemen: we only use it when disaster occurs.

It makes some important and powerful points about why people should believe fiscal stimulus is in fact stimulative. But perhaps even more than that, it's wonderful in its clarity about (a) how important empirical answers are, (b) how difficult it is to obtain empirical answers to big economic questions, and (c) that good empirical economics is often less about technique and about "shoe leather," as the former statistician David Freedman liked to say.

Also, it's just a fine example of good presentation: beautiful in its clarity of thought and persuasiveness.

Friday, November 18, 2011

Report on Farmland Values

Via Kay MacDonald, I just saw this report by the Kansas City Fed on farmland values. Some impressive gains!

They really should show a plot of value per acre, adjusted for inflation. The cumulative sum of those plotted changes would be staggering.

The Fed obviously has different farmland value data than the USDA. I'd be real interested to know the details of how values are calculated. Since there are so few land transactions I'd worry a little about parcels being comparable over time. It's probably a small issue, though.

Markets obviously expect to see commodity prices staying high for some time to come.

I'd also guess there's a lot of cash out there looking for a place to earn more than 0.1% in a money market account.

They really should show a plot of value per acre, adjusted for inflation. The cumulative sum of those plotted changes would be staggering.

The Fed obviously has different farmland value data than the USDA. I'd be real interested to know the details of how values are calculated. Since there are so few land transactions I'd worry a little about parcels being comparable over time. It's probably a small issue, though.

Markets obviously expect to see commodity prices staying high for some time to come.

I'd also guess there's a lot of cash out there looking for a place to earn more than 0.1% in a money market account.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Watch out for the ACRE program

With high commodity prices and booming farm profits, agricultural subsidies of the traditional kind have been trending down in recent years. Of course, this doesn't count the huge subsidy implicit in the ethanol mandate and subsidy paid to blenders.

But I'm wondering whether the ACRE program could be a big issue going forward. Its intent was to provide insurance against a broad decline in revenue per acre (price multiplied by yield). It achieves this by giving farmers a payment based on state-level revenues falling below 90% of a five-year average. This old Q&A by Bruce Babcock and Chad Hart explains some of the finer details.

The ACRE program, established in 2008, has had relatively modest participation so far. The low participation rates likely follow from the fact that the five-year historical average price is really low relative to what farmers now expect going forward. As time goes on, and recent higher prices get folded into the 5-year baseline guarantee, we should expect to see participation rates increase.

And then, if prices then start to decline, we could have a huge problem on our hands, with huge excess production and subsidy payments. In an environment with declining prices, the ACRE program could be hugely distortionary, which could provoke action by the WTO.

I don't presently have a strong expectation that prices will decline much going forward. But it's definitely possible. Prices are very sensitive to quantities. So a little good weather and more-than-expected production expansion in the rest of the world could bring prices down fast in another year or two, just after a lot more farmers roll into the ACRE program, motivated by this year's and (in all likelihood) next year's prices.

Here's a paper by Barry Goodwin and Vince Smith that warns about these impending dangers.

But I'm wondering whether the ACRE program could be a big issue going forward. Its intent was to provide insurance against a broad decline in revenue per acre (price multiplied by yield). It achieves this by giving farmers a payment based on state-level revenues falling below 90% of a five-year average. This old Q&A by Bruce Babcock and Chad Hart explains some of the finer details.

The ACRE program, established in 2008, has had relatively modest participation so far. The low participation rates likely follow from the fact that the five-year historical average price is really low relative to what farmers now expect going forward. As time goes on, and recent higher prices get folded into the 5-year baseline guarantee, we should expect to see participation rates increase.

And then, if prices then start to decline, we could have a huge problem on our hands, with huge excess production and subsidy payments. In an environment with declining prices, the ACRE program could be hugely distortionary, which could provoke action by the WTO.

I don't presently have a strong expectation that prices will decline much going forward. But it's definitely possible. Prices are very sensitive to quantities. So a little good weather and more-than-expected production expansion in the rest of the world could bring prices down fast in another year or two, just after a lot more farmers roll into the ACRE program, motivated by this year's and (in all likelihood) next year's prices.

Here's a paper by Barry Goodwin and Vince Smith that warns about these impending dangers.

Monday, November 14, 2011

Oil Inventories and Prices Since January 2007

Here's a plot of US oil inventories (less the Strategic Petroleum Reserve) and WTI spot oil price since January 2007. I was motivated to do this because a commenter suggested I was misleading people about what was going on with inventories around the time prices spiked in 2008. I recall following this at the time and didn't think I was misleading anyone. But then it's always good to go back and check the data, since I do promise not to mislead.

So here it is. Inventories were stable to declining when oil prices spiked. When the financial crisis hit in October 2008, growth prospects fell through the floor immediately, and then inventories started to grow. This looks like textbook commodity prices to my eyes. No telltale sign of a bubble anywhere.

If it were a bubble we'd need inventories building somewhere. That might have been in other countries or withheld supplies by producers with excess capacity. But I haven't seen any evidence of that either. And if speculators were driving things, wouldn't we expect to see that in inventories in the good ol' USA? After all, deliveries to Cushing are the most actively traded futures contracts in the world.

The data can be downloaded from the Energy Information Administration (http://www.eia.gov/).

Update: Same data, better plot.

So here it is. Inventories were stable to declining when oil prices spiked. When the financial crisis hit in October 2008, growth prospects fell through the floor immediately, and then inventories started to grow. This looks like textbook commodity prices to my eyes. No telltale sign of a bubble anywhere.

If it were a bubble we'd need inventories building somewhere. That might have been in other countries or withheld supplies by producers with excess capacity. But I haven't seen any evidence of that either. And if speculators were driving things, wouldn't we expect to see that in inventories in the good ol' USA? After all, deliveries to Cushing are the most actively traded futures contracts in the world.

The data can be downloaded from the Energy Information Administration (http://www.eia.gov/).

Update: Same data, better plot.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

It's been a long haul, but my coauthor Wolfram Schlenker and I have finally published our article with the title of this blog post in th...

-

This morning's slides. I believe slides with audio of the presentation will eventually be posted here . Open publication - Free pub...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...