I try to refrain from getting too normative on this blog. And when I do, I try to point out alternative viewpoints. But there are times when there just doesn't seem to be two sides to the story. Which brings me to ethanol subsidies and mandates, which seem like a really bad idea on almost all fronts.

It's nice to see my views have some bipartisan support.

I can see arguments in favor of subsidies for research and development for biofuels. But since long-run prospects presently seem limited, I gather these subsidies should be modest relative to, say, subsidies for R&D on battery technology and renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and ocean currents.

I can see how ethanol probably does make some sense as an un-subsidized gasoline additive. Even without further subsidies, I suspect ethanol would be significant fuel for awhile, albeit larger than it would have been had ethanol never been subsidized.

But I cannot see any good reason for the policy currently in place. Not unless oblique and inefficient transfers of wealth from taxpayers to relatively rich corn farmers, ADM, and Monsanto can be considered a pubic good.

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Sunday, November 28, 2010

Where are the $100 bills?

The basic story of depression economics is that mass unemployment, especially when combined with disinflation, is a symptom of disequilibrium.

In technical terms, it is said that an excess demand for money or safe assets is necessarily counterbalanced via Walras Law by excess supply of labor and production capacity, which we see in the forms of excess unemployment and recession.

In lay terms, this kind of disequilibrium means there is a lot of money lying on the ground--profit opportunities that are simply not being exploited. So, all we need to do to revive the economy is pick up those $100 bills.

Sounds easy. So where are they?

They probably lie in investment opportunities that are not being exploited for a complex set of reasons, perhaps fear being chief among them. With interest rates as low as they are, firms make nothing by sitting on cash, so $100 bills are lying where any profitable investment may be, no matter how small returns may be.

I see big profit opportunities in real estate, particularly in some parts of the country. When I travel I like to look up real estate prices on zillow.com and compare them to rental rates on craigslist to get a feel for the local price to rent ratio. While I haven't found a scientific way of doing this carefully, it is clear that these ratios are very attractive for buying in some cities.

The places that look best are low-to-moderate-income areas where home prices boomed and busted the most, like inland areas of California, Las Vegas, and some parts of Florida. In these places one can easily buy a home and rent it out for about 1/10 the purchase price. If, going forward, both rent and prices increase with inflation, that's a 10% real return, which is phenomenal at any time, let alone when the next best opportunity is a precarious stock market or zero interest in the bank. Places that don't look so good for investment include San Francisco, New York (especially Manhattan), and wealthier areas of DC.

I think this pattern fits what Paul Krugman has been saying about debt: as credit has tightened, savers need to spend more to make up for spending cutbacks by debtors; otherwise GDP declines. The savers generally tend to be wealthy, which can make it difficult for them to invest in lower income areas that are less familiar to them, but posses the investment opportunities. And with investment opportunities scattered among zillions of modestly priced homes that need rehabilitation, upkeep and management, it can be a tough business to get into. In contrast, locals in moderate-income areas could save a lot of money by buying rather than renting, but they can't because no one will lend to them.

It may sound crazy, but now is the time for subprime lending.

The obvious way for savers to invest in homes at an arms length is by lending to deeply indebted locals. To do this, one needs to step away from old credit models governed by FICO scores to find households that simply got burned in the crash but are likely worthy borrowers going forward. For example, if some institution were to agree to lend to families walking away from current, deeply underwater mortgage so they could buy another, much less expensive home at today's prices, both the new lender and the current underwater homeowner would gain immensely. I suspect that's a lot of people and a lot of free $100 bills.

Why isn't this happening already? I suspect it's because most of the current lending institutions fear walkaways more than they are tempted by lending opportunities, and they fear that trying to exploit the opportunities would cause more walkaways. So, for this to happen, it would take new lending institutions that are not currently holding a lot of underwater mortgages. It would also require careful analysis to develop reasonable new lending criteria.

If this did happen, I think we'd start seeing a lot more mortgage write downs, short sales, and fewer foreclosures. And with these things, higher home values in the most depressed areas, more consumer spending, more jobs, and broader economic recovery.

There must be other kinds of $100 bills lying around. I see lots of public goods, like education, where the potential returns are phenomenal. But here I'm wondering about $100 bills in private markets that simply aren't being picked up because the institutions that would normally help savers to exploit those opportunities are broken or don't exist.

In technical terms, it is said that an excess demand for money or safe assets is necessarily counterbalanced via Walras Law by excess supply of labor and production capacity, which we see in the forms of excess unemployment and recession.

In lay terms, this kind of disequilibrium means there is a lot of money lying on the ground--profit opportunities that are simply not being exploited. So, all we need to do to revive the economy is pick up those $100 bills.

Sounds easy. So where are they?

They probably lie in investment opportunities that are not being exploited for a complex set of reasons, perhaps fear being chief among them. With interest rates as low as they are, firms make nothing by sitting on cash, so $100 bills are lying where any profitable investment may be, no matter how small returns may be.

I see big profit opportunities in real estate, particularly in some parts of the country. When I travel I like to look up real estate prices on zillow.com and compare them to rental rates on craigslist to get a feel for the local price to rent ratio. While I haven't found a scientific way of doing this carefully, it is clear that these ratios are very attractive for buying in some cities.

The places that look best are low-to-moderate-income areas where home prices boomed and busted the most, like inland areas of California, Las Vegas, and some parts of Florida. In these places one can easily buy a home and rent it out for about 1/10 the purchase price. If, going forward, both rent and prices increase with inflation, that's a 10% real return, which is phenomenal at any time, let alone when the next best opportunity is a precarious stock market or zero interest in the bank. Places that don't look so good for investment include San Francisco, New York (especially Manhattan), and wealthier areas of DC.

I think this pattern fits what Paul Krugman has been saying about debt: as credit has tightened, savers need to spend more to make up for spending cutbacks by debtors; otherwise GDP declines. The savers generally tend to be wealthy, which can make it difficult for them to invest in lower income areas that are less familiar to them, but posses the investment opportunities. And with investment opportunities scattered among zillions of modestly priced homes that need rehabilitation, upkeep and management, it can be a tough business to get into. In contrast, locals in moderate-income areas could save a lot of money by buying rather than renting, but they can't because no one will lend to them.

It may sound crazy, but now is the time for subprime lending.

The obvious way for savers to invest in homes at an arms length is by lending to deeply indebted locals. To do this, one needs to step away from old credit models governed by FICO scores to find households that simply got burned in the crash but are likely worthy borrowers going forward. For example, if some institution were to agree to lend to families walking away from current, deeply underwater mortgage so they could buy another, much less expensive home at today's prices, both the new lender and the current underwater homeowner would gain immensely. I suspect that's a lot of people and a lot of free $100 bills.

Why isn't this happening already? I suspect it's because most of the current lending institutions fear walkaways more than they are tempted by lending opportunities, and they fear that trying to exploit the opportunities would cause more walkaways. So, for this to happen, it would take new lending institutions that are not currently holding a lot of underwater mortgages. It would also require careful analysis to develop reasonable new lending criteria.

If this did happen, I think we'd start seeing a lot more mortgage write downs, short sales, and fewer foreclosures. And with these things, higher home values in the most depressed areas, more consumer spending, more jobs, and broader economic recovery.

There must be other kinds of $100 bills lying around. I see lots of public goods, like education, where the potential returns are phenomenal. But here I'm wondering about $100 bills in private markets that simply aren't being picked up because the institutions that would normally help savers to exploit those opportunities are broken or don't exist.

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Adapting to a Changing Climate

I just saw this nice article in The Economist on adapting to climate change.

It's also nice that they cite my work with Wolfram Schlenker.

It would be so much easier to adapt to climate change if there weren't so much income inequality. This article does a nice job of clearly spelling out all of those challenges.

It's also nice that they cite my work with Wolfram Schlenker.

It would be so much easier to adapt to climate change if there weren't so much income inequality. This article does a nice job of clearly spelling out all of those challenges.

KIPP

I've been in DC for the holiday weekend and thinking about urban schools. So, I just read Work Hard Be Nice by Jay Mathews, in which he chronicles the remarkable work of David Levin and Mike Feinberg and their development of KIPP charter schools.

For anyone interested in improving schools and learning, you've got to read this book. It's inspiring.

A few thoughts:

(1) The youth and vigor of Teach for America teachers clearly helps. But it's also clear that Levin and Feinberg would have gotten nowhere without the mentorship of highly skilled and experienced master teachers that had strong connections to the communities where they honed their skills, especially Harriet Ball, but many others as well. It seems to me that continued efforts to find and learn from similar master teachers should be a big part of ongoing efforts in school reform.

(2) It seems a key reason white boys and girls with privileged backgrounds could succeed in teaching in poor, ethnic neighborhoods was because they went to extraordinary effort to reach out to the parents and community in a personal way.

(3) As fairly clearly chronicled in Chapter 46, more careful work needs to be done to measure the actual effectiveness of the KIPP schools in comparison to other schools. While it's clear these guys are onto something big, there are some troublesome selection issue surrounding some performance measures. Somehow some way they need to get some kids randomly assigned to KIPP and suitable controls so as to track actual progress. And someone needs to follow up with students that dropped out of KIPP and back into regular public schools or other charter schools. Furthermore, I wonder how much of KIPP's success can be traced to the selectivity of their teachers. If KIPP teachers taught somewhere else would they have be just as successful? How can we measure the success of KIPP as an institution, greater than the sum of its parts?

(4) If some charter schools like KIPP are this effective, why are we not seeing broader differences between charter schools and public schools? Is it just a matter of time? Or is KIPP truly unique?

For anyone interested in improving schools and learning, you've got to read this book. It's inspiring.

A few thoughts:

(1) The youth and vigor of Teach for America teachers clearly helps. But it's also clear that Levin and Feinberg would have gotten nowhere without the mentorship of highly skilled and experienced master teachers that had strong connections to the communities where they honed their skills, especially Harriet Ball, but many others as well. It seems to me that continued efforts to find and learn from similar master teachers should be a big part of ongoing efforts in school reform.

(2) It seems a key reason white boys and girls with privileged backgrounds could succeed in teaching in poor, ethnic neighborhoods was because they went to extraordinary effort to reach out to the parents and community in a personal way.

(3) As fairly clearly chronicled in Chapter 46, more careful work needs to be done to measure the actual effectiveness of the KIPP schools in comparison to other schools. While it's clear these guys are onto something big, there are some troublesome selection issue surrounding some performance measures. Somehow some way they need to get some kids randomly assigned to KIPP and suitable controls so as to track actual progress. And someone needs to follow up with students that dropped out of KIPP and back into regular public schools or other charter schools. Furthermore, I wonder how much of KIPP's success can be traced to the selectivity of their teachers. If KIPP teachers taught somewhere else would they have be just as successful? How can we measure the success of KIPP as an institution, greater than the sum of its parts?

(4) If some charter schools like KIPP are this effective, why are we not seeing broader differences between charter schools and public schools? Is it just a matter of time? Or is KIPP truly unique?

Friday, November 26, 2010

The Problem with Fenty and Rhee

Awhile back I suggested that Fenty lost his mayoral reelection bid mainly because schools had not performed nearly as well as had been billed in the popular press (and is still being billed--Michelle Rhee has been on Opera and even has a movie coming out).

The reality of the mayoral contest was not about those for and those against school reform. Rather, it was between those who only heard the rhetoric and believed it versus those who actually had kids in the schools and believed their lying eyes.

What Rachel Levy describes here fits much more closely with first-hand accounts I've heard:

It's a shame Rhee made such a mess of things and wasted so much money in the process.

I, for one, am a big fan of school reform and high-powered pay-for-performance incentives for teachers, even though I'm not fan of Rhee. While I'm no expert on education, it seems Rhee wasn't either; and worse, she didn't take the time to talk to those who were experts. Nor did she do her homework on the unique aspects of the District.

Going forward, the one specific thing I can constructively comment about is the IMPACT evaluation. It seems way too complex, haphazard, and easily corruptible. More importantly, it's untested. I'd prefer evaluations that placed far more weight on standardized tests, imperfect though they may be, since there are practical solutions to the most egregious problems, as I suggested here. Specifically:

1) Evaluate students based on performance on standardized tests in the subsequent grade or class.

2) Randomly assign students to teachers.

3) Use student performance in the previous class as a baseline, so that only "value added" measures of student performance are attributed to any given teacher.

More explanation following the link.

The reality of the mayoral contest was not about those for and those against school reform. Rather, it was between those who only heard the rhetoric and believed it versus those who actually had kids in the schools and believed their lying eyes.

What Rachel Levy describes here fits much more closely with first-hand accounts I've heard:

Here's what a lot of people are saying about Michelle Rhee as they sort out her legacy as chancellor of Washington D.C. public schools: Her policies were right on target and she moved city schools forward, but her big problem was simply that she didn’t play well with others. This assessment is wrong. Her reforms weren’t good policy, and criticism that her hard-charging style stifled her own well-intentioned reforms, such as is made here, misses the point.

Rhee's ideas about how to fix the ailing school system were largely misinformed, and it's no wonder: She knew little about instruction, curriculum, management, fiscal matters, and community relations. She was, to be sure, abrasive; she and Mayor Adrian Fenty, admitted as much here. But as education historian Diane Ravitch has said, "It’s difficult to win a war when you’re firing on your own troops.”

Rhee is the national face of the new brand of education reformer, so evaluation of her leadership is important not just for Washington D.C. but for the democratic institution of American public education.

Various reviews of her tenure have recently been written. This well-written and comprehensive report by Leigh Dingerson in Rethinking Schools, called "The Proving Grounds: School ’Rheeform’ in Washington, D.C" chronicles the history of D.C. public schools, Rhee’s belligerent approach to teachers, administrators, and parents, her connection to right-wing conservatives, the lack of attention given to curriculum and instruction, and the problems with her teacher-evaluation tool, IMPACT.

Not all of Rhee’s critics are liberal defenders of teachers unions; in this article in The American Spectator, Roger Kaplan makes several great points about problems with Rhee’s reign. Bill Turque, the fantastic education beat reporter for the Metro section of the Washington Post, published this succinct summary detailing the Rhee administration’s accomplishments and failures.

As a graduate of D.C. public schools and a former D.C. teacher, I offer my critique, point by point.

-0-

Rhee arrived in Washington D.C. in c. in 2007 with extraordinary power to do what she wanted. In fact, she only had her boss, Fenty, to answer to, and he never challenged her. Shortly after she started as chancellor, she met with the professionals and community leaders who had a long history of working to improve D.C. schools and promptly decided she didn’t have anything to learn from them. The die was cast.

Rhee never displayed an understanding of the city’s particular history--of political disenfranchisement, taxation without representation, and paternal federal control.

To the city’s black community, D.C. schools were a source of empowerment, autonomy, and even pride, for that community. People’s parents and extended families were educated and employed by D.C. schools. From Dingerson:

"The vast public sector employment created by the federal government helped establish a significant black middle class that supported its public schools. Many African American parents and grandparents remember their schools as neighborhood institutions and gateways to success."

Rhee paid no respect to members of the community whose elders had helped to build and fill the school system she was charged with leading. And that helped turn sentiment against her and Fenty.

-0-

A common refrain echoed by Fenty and his supporters is, "I know there were mistakes, but look at how Rhee has gotten people excited about urban public education."

Michelle Rhee did get a lot of people to pay attention to public education. Who? Many of them are unelected billionaires and conservative ideologues without any education expertise who have donated vast amounts of money to programs that have no basis in research. Some seek to privatize the public school system.

Rhee also drew some people into the profession of teaching, Who? Freshly minted graduates from highly selective colleges, teaching amateurs, most of whom don’t want to become professional teachers and who know very little about inner-city communities.

-0-

Rhee has been credited with improvements to the physical conditions of school facilities, but since June 2007, all capital planning, construction, renovation, and major repairs of D.C.P.S. school buildings have been the responsibility of the Office of Public Education Facilities Modernization, which is an agency separate from D.C. schools.

Facilities maintenance was moved from D.C. schools to the facilities modernization office in 2008. One of the reasons the office has been able to make so many improvements to public school facilities is that Fenty and the D.C. Council increased the schools’ capital budget to amounts unheard of prior to the takeover of the school system by the mayor in 2007.

-0-

Rhee and Fenty and their supporters claim -- and some critics even agree -- that under her leadership, test scores went up. But here, too, things aren’t what they seem.

First of all, standardized tests should only be used as one of many teaching tools, so test scores should certainly not be the only standard by which we measure student achievement or teacher effectiveness. Standardized tests may tell you something about the students who are taking the test, but virtually nothing about who is teaching the students taking the test. What’s more, an emphasis on standardized tests is problematic because standardized test-based content makes for lousy curricula.

As Kaplan puts it, "The substantive issue is whether it serves a useful educational purpose to turn schools into fill-the-bubble-test cram boxes instead of teaching content-rich courses."

...and...

"No one who has looked seriously at the way achievements in math and reading are assessed under the No Child Left Behind rules believes you can judge a district on the basis of scarcely a couple of years. The D.C. schools implemented reforms aimed at improving scores, anyway, in 2006, so at most Miss Rhee should claim credit for staying with them, notwithstanding her stated plan to break with business as usual."

Furthermore, according to Dingerson (and she has the data and analysis to back this up thanks to seven-year D.C math teacher and 2010 finalist for D.C. Teacher of the Year, Chris Bergfalk):

"There have been dramatic drops in standardized assessment scores, and, on closer analysis, the highly touted increases in D.C. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores are a reflection of the changing demographics of the schools, not the result of any real improvement in the quality of education provided to D.C.’s poorest and neediest students."

Finally, in this timeline of events that was developed from a series of Washington Post articles and a July 2009 D.C. schools press release, former D.C. math teacher Guy Brandenburg shows that there were questions raised about possible cheating on the D.C. Comprehensive Assessment System tests. Though asked to investigate by Deborah A. Gist, then the state superintendent of education for the District of Columbia, the Rhee administration failed to do so.

-0-

Rhee emphasized teachers over the practice of teaching. There was no focus on what or how teachers were teaching. Wrote Dingerson:

"It is worth noting that, as a so-called ’education reformer,’ Rhee has not focused on content or pedagogy. There have been no initiatives to improve teacher induction or strengthen instructional practice. The focus has remained on management and staffing, and the tone has been judgmental rather than supportive."

And Kaplan wrote:

"The core of the matter is not this or that lapse of judgment or a clumsy manner with people. She is said to be abrasive, texts even while in the midst of formal meetings. Well, you can put that down to an American get-to-the-point spirit. However, Miss Rhee never bothered to explain just what all this reform and professional development and search for ’excellent’ teachers is supposed to mean. She did not explain it to the parents. Or to anybody.”

Rhee displayed questionable knowledge of teaching practices in this stunningly inappropriate account told during a Welcome to Teachers address ( I highly recommend listening to this) of taping shut the mouths of her inner-city Baltimore students such that she caused them to bleed.

Rhee was having a classroom management crisis in her classroom and chose to respond in an unprofessional and crude way. Similarly chose narrow and crude solutions to the crisis in D.C. schools.

Although Rhee’s teacher evaluation system called IMPACT has been touted by some as "ground-breaking," it’s a flawed instrument. Valerie Strauss, a long-time education journalist at The Washington Post, discusses the flaws of IMPACT in this post on this blog.

"IMPACT is actually a collection of 20 different evaluation systems for teachers in different capacities and other school personnel. In its first iteration, teachers were to be evaluated five times a year by principals and master teachers who went into the classroom unannounced for 30 minutes and scored the teacher on 22 different teaching elements. They were, for example, supposed to show that they could tailor instruction to at least three ’learning styles,’ demonstrate that they were instilling student belief in success through "affirmation chants, poems and cheers," and a lot more. It was so nutty to think that any teacher would show all 22 elements in 30 minutes that officials modified it. Now the number is a still unrealistic 10 or so. Some teachers, fearing that their professional careers were being based on an unfair system, got someone in the front office to alert them to when the principal or master teacher was to show up, according to interviews with a number of teachers who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Then they would send difficult kids out of the classroom, and, in some cases, pull out a specially prepared lesson plan tailored to meet IMPACT requirements. Meanwhile, some teachers never got five evaluations, apparently because a number of master teachers hired to do the jobs quit, according to sources in the school system."

Many teachers deemed "ineffective" by IMPACT were actually solid, experienced teachers, while others who were deemed "effective" were some of the weakest teachers in their schools.

-0-

The ultimate questions to ask about Rhee are not about whether she was liked or disliked, nice or mean.

They are, instead: Did she have sound and informed ideas about curriculum, fiscal and personnel management, education, and the craft of teaching? Were her policies and reforms effective? Did they improve the quality of public education in the District of Columbia? Did she adequately serving the communities and families she was hired to serve?

The answer to those questions is "no."

Rhee’s successor, Interim Chancellor Kaya Henderson was Rhee’s right hand woman. Henderson is similarly inexperienced (a few years of teaching in Teach for America before going into administration) and holds carbon-copy ideas about education to her former boss.

Rhee supporters are pleased, saying that she will continue the reforms but is more likely than Rhee to be collaborative. But collaboration and consensus would require that Henderson compromise on the reform narrow, ideological, and inflexible platform.

Is Henderson prepared to give up her ideology or will she continue along the same path as Rhee, but just be kinder along the way?

We’ll be watching.

It's a shame Rhee made such a mess of things and wasted so much money in the process.

I, for one, am a big fan of school reform and high-powered pay-for-performance incentives for teachers, even though I'm not fan of Rhee. While I'm no expert on education, it seems Rhee wasn't either; and worse, she didn't take the time to talk to those who were experts. Nor did she do her homework on the unique aspects of the District.

Going forward, the one specific thing I can constructively comment about is the IMPACT evaluation. It seems way too complex, haphazard, and easily corruptible. More importantly, it's untested. I'd prefer evaluations that placed far more weight on standardized tests, imperfect though they may be, since there are practical solutions to the most egregious problems, as I suggested here. Specifically:

1) Evaluate students based on performance on standardized tests in the subsequent grade or class.

2) Randomly assign students to teachers.

3) Use student performance in the previous class as a baseline, so that only "value added" measures of student performance are attributed to any given teacher.

More explanation following the link.

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Leonardt on Cultivating Chinese Consumption

This is a nice article by Leonardt.

But somehow it all seems too long and complicated for the reality of the situation.

The main obstacle for China, and a big one for the U.S. and the rest of the world, is explained in a single paragraph.

That would be good for China. And everyone else.

But somehow it all seems too long and complicated for the reality of the situation.

The main obstacle for China, and a big one for the U.S. and the rest of the world, is explained in a single paragraph.

...By buying large amounts of United States Treasury bonds (and, to a lesser extent, Japanese and European bonds), China has kept its currency artificially low. The renminbi has roughly the same value today as it did in 1990, relative to a basket of other currencies, which is remarkable considering how much faster China’s economy has grown than the world economy. The low renminbi holds down the price of Chinese-made goods in other countries, increasing exports. But it also means that foreign-made products are more expensive within China than they would otherwise be. In effect, China’s government is deliberately reducing the buying power of its own consumers to subsidize its exporters.Lower prices and they will spend.

That would be good for China. And everyone else.

ideaHarvest, another agricultural economics blog

Barrett Kirwan, another agricultural economist and good friend and colleague, has started a blog called ideaHarvest

It's now added to the blogroll.

It's cool to see other assistant professors jump into this.

But despite what some might say, this is still risky business for untenured blokes like us.

It's now added to the blogroll.

It's cool to see other assistant professors jump into this.

But despite what some might say, this is still risky business for untenured blokes like us.

Monday, November 22, 2010

Additivity and Payments for Ecosystem Services, Take Two

Awhile back I wrote a couple vague posts about PES and additivity (also, here). I am going to try to clarify my thinking a little. All of this comes in response to a great workshop on payments for ecosystem services, sometimes called payments for environmental services, that was held in Chapel Hill a couple weeks ago. The workshop was hosted by the Property and Environment Research Center, a Libertarian think tank based in Bozeman, MT. PERC is headed by Terry Anderson who has long espoused "free market environmentalism." His broad thesis is that, with well-defined property rights, private markets can solve environmental problems more efficiently and effectively than government regulation.(**)

While PERC has what some might consider fringe Libertarian underpinnings, for this workshop they corralled a broad group of interesting participants with varied (or non-) ideological leanings. It was also relatively small, with lots of time set aside for discussion. As James Salzman said at the meeting, PES is an interesting concept that can bring together people with very different ideological leanings.

My role was a small one: I just served as a discussant for one of the papers. I used my five minutes to present my basic thinking on the so-called problem of making payments for ecosystem services "additive," which really underlies the paper I discussed, and several others. My simple diagrammatic analysis is below, followed by a brief description.

In my view, attempts to make PES additional--that is, pay only for ecosystem services that would not have been provided otherwise--are really attempts at price discrimination. Now, the term "price discrimination" has derisive overtones that it really shouldn't. We see price discrimination everywhere and there are some really positive aspects to it. Consider how much plane ticket prices vary across passengers on a typical flight. Price discrimination often allows people to enjoy a good or service that otherwise wouldn't, especially in monopolistically competitive markets. But price discrimination is the term we're stuck with, because that's what's in all the textbooks.

The challenge with price discrimination, in all contexts, is that it's basically impossible to do perfectly. In the context of PES, perfect price discrimination would have all payments for provision of ecosystem services just equal landowners' opportunity cost for participating, not a penny more.

Now, since you cannot discriminate perfectly, there are going to be inefficiencies. The trick is to figure out how to minimize those inefficiencies, which takes things to the beautifully intricate world of contract theory and mechanism design. Paul Ferraro has a couple nice papers summarizing this theory in the context of PES.

To make all of this more concrete, let's take a real world example, the Conservation Reserve Program, which is arguably the world's largest PES program. CRP pays farmers annual rental payments to establish conservation practices on land formerly planted with crops. Last time I checked, annual payments totaled around $1.8 billion to retire some 34 million acres (about the size of North Carolina).

How does CRP price discriminate? Several ways. First, farmers cannot enroll land in CRP unless it has been cropped for three of the previous five years (or has already been enrolled in CRP). In effect, owners of uncropped land have zero opportunity cost for providing much of the environmental services associated with that land, so CRP excludes uncropped land since it costs those landowners nothing to provide environmental services, even though there is positive marginal social value to the services provided.

Second, while CRP uses a competitive auction-like environment for enrolling land, landowners opportunity costs vary widely across participants, so the government price discriminates by putting a county and soil-specific maximums on the on rental rates that farmers can request. Getting these maximums right can be tricky, as I've noted previously. But the essential idea here is price discrimination.

Third, the competitive nature of the CRP bidding mechanism encourages landowners to make offers that are somewhat closer to their opportunity costs. However, these incentives are limited, since landowners will still tend to make offers that tend toward the expected equilibrium price, not their opportunity costs for participating. I'm in the midst of putting the final touches on a long overdue paper that considers new procurement auction mechanisms that might price discriminate more effectively than standard auctions.

The broader point is that addititivity, or lackthereof, really has no direct bearing on the efficiency of PES programs, but rather the distribution of rents that derive from them. The more price discriminating the PES program, the more "buyers" will gain and the less sellers (typically landowners) gain. What's really interesting, however, is that from the buyers' point of view, price discrimination is really necessary. Otherwise, they may find themselves paying largely for environmental services that would have been provided anyway. And while social surplus may grow, the implicit transfer from buyers to sellers is larger than the total increase in surplus.

While I think this illustration of the problem does a lot to clarify some difficult tensions, it certainly doesn't provide any clear answers. It's always hard to figure out how to split a pie. And, in this case, there are almost certainly going to be tradeoffs between the size of the pie and how it is split.(##) But this is not going to be the usual inequity verses efficiency tradeoff one usually envisions. For example, some poorer countries with lots of rain forest could gain the most from a relatively more competitive (and less additive) market for carbon offsets.

Clearly, the largest problem involved with developing a true market for ecosystem services is corralling the broad, diverse and typically non-excludable interests that make up the "buyers" or consumers of ecosystem services. The large transactions costs associated with corralling these interests is the obvious challenge to Coasian solutions that do not involve government. In my view, this standard challenge is exacerbated further by the difficult tensions between efficiency and rent distribution. Because, if buyers could corral their broad and diverse interests and establish new trade for ecosystem services, they may see that such efforts would ultimately be self-defeating.

(**) This idea follows a classic paper by Coase. Where PERC may be more fringe than mainstream economists concerns where "property rights" ultimately come from. Many economists (myself included) think that government often needs to play a larger role in defining and protecting property rights. Terry Andersen and PERC seem to have a relatively narrow view of property rights, one in which the law and government might be involved with enforcing private contracts, but very little beyond that. But where individual economists draw the box around the government role in defining property rights seems to me like mushy territory.

(##) Economists like to fantasize about lump sum transfers as a way to have the largest possible pie and then split it, but in reality that almost never happens.

While PERC has what some might consider fringe Libertarian underpinnings, for this workshop they corralled a broad group of interesting participants with varied (or non-) ideological leanings. It was also relatively small, with lots of time set aside for discussion. As James Salzman said at the meeting, PES is an interesting concept that can bring together people with very different ideological leanings.

My role was a small one: I just served as a discussant for one of the papers. I used my five minutes to present my basic thinking on the so-called problem of making payments for ecosystem services "additive," which really underlies the paper I discussed, and several others. My simple diagrammatic analysis is below, followed by a brief description.

SLIDES HERE:

In my view, attempts to make PES additional--that is, pay only for ecosystem services that would not have been provided otherwise--are really attempts at price discrimination. Now, the term "price discrimination" has derisive overtones that it really shouldn't. We see price discrimination everywhere and there are some really positive aspects to it. Consider how much plane ticket prices vary across passengers on a typical flight. Price discrimination often allows people to enjoy a good or service that otherwise wouldn't, especially in monopolistically competitive markets. But price discrimination is the term we're stuck with, because that's what's in all the textbooks.

The challenge with price discrimination, in all contexts, is that it's basically impossible to do perfectly. In the context of PES, perfect price discrimination would have all payments for provision of ecosystem services just equal landowners' opportunity cost for participating, not a penny more.

Now, since you cannot discriminate perfectly, there are going to be inefficiencies. The trick is to figure out how to minimize those inefficiencies, which takes things to the beautifully intricate world of contract theory and mechanism design. Paul Ferraro has a couple nice papers summarizing this theory in the context of PES.

To make all of this more concrete, let's take a real world example, the Conservation Reserve Program, which is arguably the world's largest PES program. CRP pays farmers annual rental payments to establish conservation practices on land formerly planted with crops. Last time I checked, annual payments totaled around $1.8 billion to retire some 34 million acres (about the size of North Carolina).

How does CRP price discriminate? Several ways. First, farmers cannot enroll land in CRP unless it has been cropped for three of the previous five years (or has already been enrolled in CRP). In effect, owners of uncropped land have zero opportunity cost for providing much of the environmental services associated with that land, so CRP excludes uncropped land since it costs those landowners nothing to provide environmental services, even though there is positive marginal social value to the services provided.

Second, while CRP uses a competitive auction-like environment for enrolling land, landowners opportunity costs vary widely across participants, so the government price discriminates by putting a county and soil-specific maximums on the on rental rates that farmers can request. Getting these maximums right can be tricky, as I've noted previously. But the essential idea here is price discrimination.

Third, the competitive nature of the CRP bidding mechanism encourages landowners to make offers that are somewhat closer to their opportunity costs. However, these incentives are limited, since landowners will still tend to make offers that tend toward the expected equilibrium price, not their opportunity costs for participating. I'm in the midst of putting the final touches on a long overdue paper that considers new procurement auction mechanisms that might price discriminate more effectively than standard auctions.

The broader point is that addititivity, or lackthereof, really has no direct bearing on the efficiency of PES programs, but rather the distribution of rents that derive from them. The more price discriminating the PES program, the more "buyers" will gain and the less sellers (typically landowners) gain. What's really interesting, however, is that from the buyers' point of view, price discrimination is really necessary. Otherwise, they may find themselves paying largely for environmental services that would have been provided anyway. And while social surplus may grow, the implicit transfer from buyers to sellers is larger than the total increase in surplus.

While I think this illustration of the problem does a lot to clarify some difficult tensions, it certainly doesn't provide any clear answers. It's always hard to figure out how to split a pie. And, in this case, there are almost certainly going to be tradeoffs between the size of the pie and how it is split.(##) But this is not going to be the usual inequity verses efficiency tradeoff one usually envisions. For example, some poorer countries with lots of rain forest could gain the most from a relatively more competitive (and less additive) market for carbon offsets.

Clearly, the largest problem involved with developing a true market for ecosystem services is corralling the broad, diverse and typically non-excludable interests that make up the "buyers" or consumers of ecosystem services. The large transactions costs associated with corralling these interests is the obvious challenge to Coasian solutions that do not involve government. In my view, this standard challenge is exacerbated further by the difficult tensions between efficiency and rent distribution. Because, if buyers could corral their broad and diverse interests and establish new trade for ecosystem services, they may see that such efforts would ultimately be self-defeating.

(**) This idea follows a classic paper by Coase. Where PERC may be more fringe than mainstream economists concerns where "property rights" ultimately come from. Many economists (myself included) think that government often needs to play a larger role in defining and protecting property rights. Terry Andersen and PERC seem to have a relatively narrow view of property rights, one in which the law and government might be involved with enforcing private contracts, but very little beyond that. But where individual economists draw the box around the government role in defining property rights seems to me like mushy territory.

(##) Economists like to fantasize about lump sum transfers as a way to have the largest possible pie and then split it, but in reality that almost never happens.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Eggertsson and Krugman

I don't know how many economists have been reading the new paper by Eggertsson and Krugman. I just gave it a once over. I didn't check the math that wasn't obvious but I could see how the equations fit together, and the intuition made sense.

For me, anyway, this model adds a whole lot of clarity to the current situation, many past recessions, and macroeconomics in general. I feel it is destined to be a classic.

The backward bending AD curve is really interesting.

One thing they didn't mention: The idea of a threshold level of debt that changes in "the Minsky moment" melds very nicely not only with standard models of asymmetric information (a la Stiglitz and Weiss) but also with the well documented empirical link between risk premiums and business cycles. When risk, or at least perceived risk, goes up, threshold debt levels naturally decline in asymmetric information models.

The model needs more dynamics. It would also be nice if the model included both risky and safe assets. But it seems unlikely that these will change anything substantive.

For me, this makes the link between micro and macro in way that actually makes sense.

Update: By "makes sense" I mean that the model uses a mechanism that draws a more plausible link between the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers, the financial collapse, and the ensuing recession. Awhile back I speculated that a better model would draw more explicit link between micro asymmetric information models (like Stiglitz and Weiss, which shows how credit rationing occurs) and aggregate demand shocks.

To me anyway, this makes way more sense than real productivity shocks or stochastic laziness as the principal driver of business cycles. If one were to try and generalize this model by Eggertsson and Krugman, I can imagine there being real shocks in perceived uncertainty that then feeds back into macroeconomy through deleveraging cycles. So, the source of recessions need not be actual productivity shocks, just some increased uncertainty about the future, which may or may not have anything to do with fundamental productivity. Even political uncertainty would do. The real economic effect comes later through the develeraging cycles.

Update: Nick Rowe has a very nice review of the article.

For me, anyway, this model adds a whole lot of clarity to the current situation, many past recessions, and macroeconomics in general. I feel it is destined to be a classic.

The backward bending AD curve is really interesting.

One thing they didn't mention: The idea of a threshold level of debt that changes in "the Minsky moment" melds very nicely not only with standard models of asymmetric information (a la Stiglitz and Weiss) but also with the well documented empirical link between risk premiums and business cycles. When risk, or at least perceived risk, goes up, threshold debt levels naturally decline in asymmetric information models.

The model needs more dynamics. It would also be nice if the model included both risky and safe assets. But it seems unlikely that these will change anything substantive.

For me, this makes the link between micro and macro in way that actually makes sense.

Update: By "makes sense" I mean that the model uses a mechanism that draws a more plausible link between the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers, the financial collapse, and the ensuing recession. Awhile back I speculated that a better model would draw more explicit link between micro asymmetric information models (like Stiglitz and Weiss, which shows how credit rationing occurs) and aggregate demand shocks.

To me anyway, this makes way more sense than real productivity shocks or stochastic laziness as the principal driver of business cycles. If one were to try and generalize this model by Eggertsson and Krugman, I can imagine there being real shocks in perceived uncertainty that then feeds back into macroeconomy through deleveraging cycles. So, the source of recessions need not be actual productivity shocks, just some increased uncertainty about the future, which may or may not have anything to do with fundamental productivity. Even political uncertainty would do. The real economic effect comes later through the develeraging cycles.

Update: Nick Rowe has a very nice review of the article.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

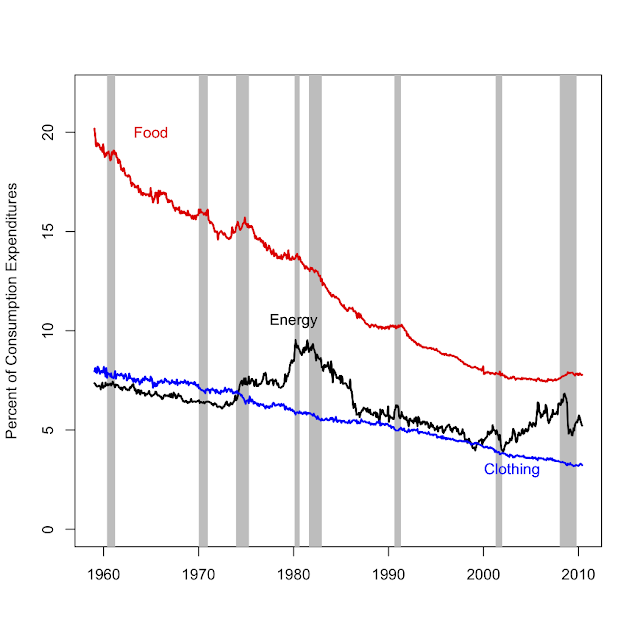

Energy, food and clothing expenditures as share of total expenditures

I haven't posted a graph in awhile, so here is one I just made for a presentation I will give today.

The plot shows the percent of household consumption expenditures on food, clothing and footwear, and energy (NIPA accounts, downloaded from EconStats: http://www.econstats.com/nipa/ ).

The grey bands are recessions.

There's not too much to say about this that isn't obvious. Volatile energy prices explain the fluctuations in energy consumption shares, and these are often associated with recessions. Food and clothing shares have shown a steady trend down, as production efficiency has increased and prices have fallen [relative to income]. Demand is relatively inelastic which means the consumption share has declined with [relative] price, even though per-capita quantities have increased (the obseity problem, larger closets, etc.) The smoothness of food and clothing expenditures also attest to inelastic demand and perhaps the monopolistically competitive nature of retail businesses that sell these products. That is, retailers probably absorb much of the fluctuations in costs. Finally, notice how the food share increases a bit during recessions. That's mainly because total consumption expenditures (the denominator) goes down and food expenditures hardly change.

So, where do consumers cut back when energy prices and expenditure shares spike? That would be durable goods, like cars and appliances (not shown).

Update: Jim MacDonald (comment below) is right. It's prices relative to income that have fallen, but this is much more about income growth than falling prices.

Also, I'm speculating on the fluctuations part. I'd guess there is near full pass through of costs to price in the long run but not in the short run, just based on my intuition of monopolistically competitive markets. Empirically, I cannot really draw that conclusion from the graph because costs are mostly labor anyway, and labor costs tend to be smooth anyway.

The plot shows the percent of household consumption expenditures on food, clothing and footwear, and energy (NIPA accounts, downloaded from EconStats: http://www.econstats.com/nipa/ ).

The grey bands are recessions.

There's not too much to say about this that isn't obvious. Volatile energy prices explain the fluctuations in energy consumption shares, and these are often associated with recessions. Food and clothing shares have shown a steady trend down, as production efficiency has increased and prices have fallen [relative to income]. Demand is relatively inelastic which means the consumption share has declined with [relative] price, even though per-capita quantities have increased (the obseity problem, larger closets, etc.) The smoothness of food and clothing expenditures also attest to inelastic demand and perhaps the monopolistically competitive nature of retail businesses that sell these products. That is, retailers probably absorb much of the fluctuations in costs. Finally, notice how the food share increases a bit during recessions. That's mainly because total consumption expenditures (the denominator) goes down and food expenditures hardly change.

So, where do consumers cut back when energy prices and expenditure shares spike? That would be durable goods, like cars and appliances (not shown).

Update: Jim MacDonald (comment below) is right. It's prices relative to income that have fallen, but this is much more about income growth than falling prices.

Also, I'm speculating on the fluctuations part. I'd guess there is near full pass through of costs to price in the long run but not in the short run, just based on my intuition of monopolistically competitive markets. Empirically, I cannot really draw that conclusion from the graph because costs are mostly labor anyway, and labor costs tend to be smooth anyway.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

If China were to let its currency float, commodity prices would soar

But this would be a good thing.

Krugman says China's currency is clearly undervalued. Clearly, he's right. And this is hurting China, hurting the US, and hurting the whole world's economy. China could solve their inflation problems without curbing growth by simply letting their currency float. And their proposed price controls could make things a lot worse.

Now, if China were to abandon these destructive policies, I think it's also clear that commodity prices would soar, at least as measured in dollars. (Prices would fall in Renminbi, and perhaps other currencies.) This would likely elicit howls from some who might fear that rising oil prices would stifle domestic recovery.

But I think those fears would be misplaced. Because while oil and other commodity prices would rise, so would foreign and domestic demand for goods produced in the U.S. This would stimulate our economy and push us back toward full employment and capacity utilization. That is, commodity prices would rise due to a demand shock, which is quite unlike the supply shocks prevalent in our history.

The phenomenon would be much like some of commodity price increases we've seen recently with QE2 and a falling dollar.

Anyway, I'm just trying to emphasize that not all commodity price shocks are the same, and I think we currently have little to worry about--in terms of impacts on inflation or broader economic activity--from commodity price increases stemming from a weakening dollar.

Krugman says China's currency is clearly undervalued. Clearly, he's right. And this is hurting China, hurting the US, and hurting the whole world's economy. China could solve their inflation problems without curbing growth by simply letting their currency float. And their proposed price controls could make things a lot worse.

Now, if China were to abandon these destructive policies, I think it's also clear that commodity prices would soar, at least as measured in dollars. (Prices would fall in Renminbi, and perhaps other currencies.) This would likely elicit howls from some who might fear that rising oil prices would stifle domestic recovery.

But I think those fears would be misplaced. Because while oil and other commodity prices would rise, so would foreign and domestic demand for goods produced in the U.S. This would stimulate our economy and push us back toward full employment and capacity utilization. That is, commodity prices would rise due to a demand shock, which is quite unlike the supply shocks prevalent in our history.

The phenomenon would be much like some of commodity price increases we've seen recently with QE2 and a falling dollar.

Anyway, I'm just trying to emphasize that not all commodity price shocks are the same, and I think we currently have little to worry about--in terms of impacts on inflation or broader economic activity--from commodity price increases stemming from a weakening dollar.

Monday, November 15, 2010

Another take on QE2 and commodity prices

Thin posting these days because I've been way too busy with travel and other things, and really don't have time for blogging. At some point I hope to write something about a great meeting on PES (that's Payments for Ecosystem Services) in Chapel Hill last week and a trip to Illinois where I gave a seminar and had some great discussions Scott Irwin.

For now, here's a brief follow up to a post a couple weeks ago where I critiqued Jim Hamilton's post on the effect of negative real interest rates on commodity prices. That argument didn't convince me. But in a more recent post he now says that decline in value of the dollar seems to be driving broad increases in the prices of commodities. On this point I agree. A weaker dollar is likely driving up commodity prices, and the decline in the dollar probably has something to do with QE2.

But I guess I don't see this as especially ominous. Commodity prices are a very small share of retail prices in this country and all other developed nations. Only oil prices have an appreciable influence on anything, and even that is far less than it once was. It will take a heck-of-a-lot more dollar weakness for commodity price increases to show up in retail price increases---ie., actual inflation. Moreover, if other countries--particularly European--were were to engage in their own QE programs, I don't think we'd even see commodity price increases.

A brief side note: One of Jim Hamilton's most famous lines of research (which actually inspired my own dissertation work) is about the link between oil prices and the macroeconomy. I think it's important to note that not all oil price shocks are alike (or, more generally, commodity price shocks in general). The price shocks prevalent in Jim's work, and through much of history, have to do with supply shocks or anticipated supply shocks (eg., speculative storage in light of unrest in the middle east). But the spike in 2008, and currency-related effects we're seeing now, and shocks we're most likely to see in the future, are demand shocks, not supply shocks. And this difference, I think, has very different implications for the macroeconomy.

I'm just an armchair macro guy. But right now I'm with the Krugman-Delong front[1, 2, 3, 4]. I just don't see how inflation could possibly be a major concern given most of what we consume is (a) rent or (b) mostly comprised of wages to labor. Neither rent nor wages are going up unless the economy recovers fast. No one thinks that's happening. And even in the off chance the economy were to suddenly return to full employment and thus give rise to real inflation fears, the Fed would reverse QE2 in a nanosecond, thereby deflating those inflationary fears.

I understand some people are genuinely fearful of inflation. But on an intellectual level, I just don't understand why

For now, here's a brief follow up to a post a couple weeks ago where I critiqued Jim Hamilton's post on the effect of negative real interest rates on commodity prices. That argument didn't convince me. But in a more recent post he now says that decline in value of the dollar seems to be driving broad increases in the prices of commodities. On this point I agree. A weaker dollar is likely driving up commodity prices, and the decline in the dollar probably has something to do with QE2.

But I guess I don't see this as especially ominous. Commodity prices are a very small share of retail prices in this country and all other developed nations. Only oil prices have an appreciable influence on anything, and even that is far less than it once was. It will take a heck-of-a-lot more dollar weakness for commodity price increases to show up in retail price increases---ie., actual inflation. Moreover, if other countries--particularly European--were were to engage in their own QE programs, I don't think we'd even see commodity price increases.

A brief side note: One of Jim Hamilton's most famous lines of research (which actually inspired my own dissertation work) is about the link between oil prices and the macroeconomy. I think it's important to note that not all oil price shocks are alike (or, more generally, commodity price shocks in general). The price shocks prevalent in Jim's work, and through much of history, have to do with supply shocks or anticipated supply shocks (eg., speculative storage in light of unrest in the middle east). But the spike in 2008, and currency-related effects we're seeing now, and shocks we're most likely to see in the future, are demand shocks, not supply shocks. And this difference, I think, has very different implications for the macroeconomy.

I'm just an armchair macro guy. But right now I'm with the Krugman-Delong front[1, 2, 3, 4]. I just don't see how inflation could possibly be a major concern given most of what we consume is (a) rent or (b) mostly comprised of wages to labor. Neither rent nor wages are going up unless the economy recovers fast. No one thinks that's happening. And even in the off chance the economy were to suddenly return to full employment and thus give rise to real inflation fears, the Fed would reverse QE2 in a nanosecond, thereby deflating those inflationary fears.

I understand some people are genuinely fearful of inflation. But on an intellectual level, I just don't understand why

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

I thought I understood the idea of inflation targeting....

...until I read this utterly confounding post by Paul Krugman.

Whether you love him or hate him, one must admit this is unusual for PK. Usually he is exceptionally clear and logical. I suspect there probably is some deeper logic here than meets the (or at least my) eye, and I suspect we'll be hearing a lot more from Krugman and others on inflation targeting.

There is also the possibility that my skull is thicker than usual this evening.

In any case, kudos to him for finally writing more about the topic. I was kinda wishing he and others would have done more of this, oh back in February of 2009.

In the meantime, I really like Jim Hamilton's perspective on the issue. The basic idea is to always have a long-run inflation target in mind, say 2%. Then, have medium-run targets for inflation that take into account cumulative off-target inflation in the past. So, following a few quarters of disinflation, the Fed should target a somewhat higher inflation target going forward to make up for below-target inflation in the past. The more disinflation we have, the more the Fed should target "catch up" inflation in the future. This seems like a naturally stabilizing policy that is also very conducive to long run stability of expectations. I also think it is deeply true to Fiedman's monetarism--the kind of thing that might elicit support of economists across a broad spectrum. After all, Bernanke does have to carry along an unusually divisive Federal Open Market Committee. I also think it would work a lot better than a vague QE2 policy would.

Update: I also like Karl Smith's line on inflation targeting: permanently change the target to 4%. Even a permanent change to 3% may do the trick. Besides the many reasons Karl gives, one biggie is that this reduces the chance that we'll hit the zero lower bound in future recessions. (I think he alludes to this when he says it will "serve as a buffer against future economic crises...") There is also good bit of reasoning and evidence that a modest amount of inflation reduces the amount of real wage rigidity in the economy, which effectively reduces the incidence of and depth of recessions. I think this is a good reason for a higher target inflation rate even if we weren't stuck in a liquidity trap. If the Fed were to say as much it could be a big shock to help push things along. Even though there is no indication at all that they plan to do such a thing, after another year or two of stagnation, they just might. After all, Janet Yellen has done some of the work suggesting a higher inflation rate is probably better for the economy anyhow.

Whether you love him or hate him, one must admit this is unusual for PK. Usually he is exceptionally clear and logical. I suspect there probably is some deeper logic here than meets the (or at least my) eye, and I suspect we'll be hearing a lot more from Krugman and others on inflation targeting.

There is also the possibility that my skull is thicker than usual this evening.

In any case, kudos to him for finally writing more about the topic. I was kinda wishing he and others would have done more of this, oh back in February of 2009.

In the meantime, I really like Jim Hamilton's perspective on the issue. The basic idea is to always have a long-run inflation target in mind, say 2%. Then, have medium-run targets for inflation that take into account cumulative off-target inflation in the past. So, following a few quarters of disinflation, the Fed should target a somewhat higher inflation target going forward to make up for below-target inflation in the past. The more disinflation we have, the more the Fed should target "catch up" inflation in the future. This seems like a naturally stabilizing policy that is also very conducive to long run stability of expectations. I also think it is deeply true to Fiedman's monetarism--the kind of thing that might elicit support of economists across a broad spectrum. After all, Bernanke does have to carry along an unusually divisive Federal Open Market Committee. I also think it would work a lot better than a vague QE2 policy would.

Update: I also like Karl Smith's line on inflation targeting: permanently change the target to 4%. Even a permanent change to 3% may do the trick. Besides the many reasons Karl gives, one biggie is that this reduces the chance that we'll hit the zero lower bound in future recessions. (I think he alludes to this when he says it will "serve as a buffer against future economic crises...") There is also good bit of reasoning and evidence that a modest amount of inflation reduces the amount of real wage rigidity in the economy, which effectively reduces the incidence of and depth of recessions. I think this is a good reason for a higher target inflation rate even if we weren't stuck in a liquidity trap. If the Fed were to say as much it could be a big shock to help push things along. Even though there is no indication at all that they plan to do such a thing, after another year or two of stagnation, they just might. After all, Janet Yellen has done some of the work suggesting a higher inflation rate is probably better for the economy anyhow.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

VOTE, even though it's irrational

Voting may be the biggest prisoner's dilemma ever.

That is, it's smart for one and dumb for all to NOT vote.

Thankfully, many of us do it anyway. If we didn't, democracy wouldn't work.

Some, including at least one of my colleagues, isn't sure whether democracy does work. I personally shudder thinking about the alternative.

The good news is that, despite it being irrational to do so, turnout expert Dr. Michael McDonald is predicting a turnout of 90 million people (hat tip to electoral-vote.com). Good weather may push things even higher.

So. Join the irrational masses and vote already!

That is, it's smart for one and dumb for all to NOT vote.

Thankfully, many of us do it anyway. If we didn't, democracy wouldn't work.

Some, including at least one of my colleagues, isn't sure whether democracy does work. I personally shudder thinking about the alternative.

The good news is that, despite it being irrational to do so, turnout expert Dr. Michael McDonald is predicting a turnout of 90 million people (hat tip to electoral-vote.com). Good weather may push things even higher.

So. Join the irrational masses and vote already!

QE2 and Commodity Prices

Over at Econbrowser (one of my favorite blogs) Jim Hamilton is worried about the effects of QE2 (or negative real interest rates) on commodity prices.

He writes:

The top panel is a proxy for real interest rates: the 6-month t-bill rate minus realized inflation over the subsequent six months. The bottom graph is a percentage change in the producer price index for a 12 month period.

There does appear to be a correlation, one that is stronger during some periods as compared to others (particularly the 70s and 80s, something I'll come back to). Jim Hamilton's implicit assumption is that causation goes from the top panel to the bottom panel. But is it possible that causation goes the other way, from producer price changes to consumer price changes, and thus reduction in the real rate of return?

Well, yes.

One clue is the tremendous volatility of real interest rates. True real interest rates are not that variable. Consider, for example, rates of return on inflation indexed treasury bills. Those rates don't exist for as long a time series as the top panel above, but for the time period that does exist, they are nowhere near as variable as Jim's series. The problem is that short term inflation measures are noisy, often driven by fluctuations in food and energy prices, and these fluctuations are not anticipated in advance. Only expected changes in inflation should get priced in the real rate.

Second, much of volatility of in the producer price index--whatever the fundamental source--gets passed along to the consumer price index. So, say there's an embargo of oil from Iran and oil prices spike. We'll eventually see that in retail prices and the CPI. The price spike in turn causes the real interest rate to decline. So, there's good reason to think causation goes from the bottom graph to the top graph, rather than vice versa. That is, almost surely, what's going on in the 70s and 80s, which is where the link is strongest. I'd venture to guess that's the main source of correlation throughout.

So, in a nutshell, I'm not worried about the effect of QE2, or generally low or negative interest rates, on commodity prices. If commodity prices go up, I think that will mainly be a symptom of demand growth, which would be a good thing--a sign of recovery--for aggregate economies. Alternatively, prices could go up from real supply shocks and/or trade restrictions, which would obviously be bad things. But whatever may happen to prices, I think QE2 will be a very small deal.

He writes:

What does a negative real rate signify? If you consider a simple one-good economy in which the output is costlessly storable, a negative real rate could never happen-- people would simply hoard the good rather than buy such miserable assets. You're better off storing a can of tuna for a year than messing with T-bills at the moment. But there's only so much tuna you can use, and many expenditures you might want to save for can't really be stored in your closet for the next year. It's perfectly plausible from the point of view of more realistic economic models that we could see negative real interest rates, at least for a while.

Even so, within those models, there's an incentive to buy and hold those goods that are storable. And in terms of the historical experience, episodes of negative real interest rates have usually been associated with rapidly rising commodity prices.

There are two issues here, theory and evidence. First let's reconsider the theory.

Storage is tied not only to interest rates, but also (and more importantly, I believe) to anticipated future changes in prices, as well as physical storage costs. If people start to hoard commodities then current prices will go up. This happens because storing commodities means not consuming them, and as we consume less, the marginal value of consumption goes up. That can of tuna on the shelf starts looking real tasty the hungrier one gets! At the same time, storing commodities means consuming more in the future, which means the future price--the future marginal value of consumption--goes down. All the more reason to consume that can of tuna today if you're hungry and the large quantity you expect to eat tomorrow will make you sick.

Now, at the margin, interest rates certainly do affect the decision to store. The question is how much. The answer, I think, is very little. With commodities, that demand curve is very steep. The marginal value decreases sharply with consumption, so it is a big part of the calculation. If interest rates are the only thing driving growth in inventories, this will cause the expected price change between the present and the future to go down. Also, as hoarding increases, the marginal costs of storage likely increase. So, for small interest rate changes, the relative tradeoff is small, even if interest rates go negative.

My point here is that it's hard for me to see large-scale hoarding even in an environment with negative real interest rates. Hoarding can only happen if markets irrationally believe that price increases will be sustained indefinitely--i.e., a speculative bubble. Hopefully markets will be wary of such things after recent experience in housing and stock market prices.

Besides, when has a speculative bubble occurred with commodities? I know price spikes have occurred when some have tried to corner certain markets, but I think that's different. We've also had price spikes when inventories were depleted, there was real worry of impending supply shocks, or trade policies interfered with international commodity trading. But these are all very different stories as well.

Jim doesn't hint at a bubble. Instead, he's assuming the demand curve is flat. In reality, it's really very steep.

Second, let's consider the evidence. Professor Hamilton presents two graphs, one with a proxy for real interest rates, the second a plot of real wholesale price changes. I lifted those graphs from Econbrowser and pasted them below:

Jim doesn't hint at a bubble. Instead, he's assuming the demand curve is flat. In reality, it's really very steep.

Second, let's consider the evidence. Professor Hamilton presents two graphs, one with a proxy for real interest rates, the second a plot of real wholesale price changes. I lifted those graphs from Econbrowser and pasted them below:

Top panel: S6-month T-bill rate (secondary market from FRED) minus CPI inflation rate (annual rate) over subsequent six months, 1959:M1-2010:M3. Bottom panel: annual percentage change in producer price index for all commodities for 12 months ending at indicated date.

The top panel is a proxy for real interest rates: the 6-month t-bill rate minus realized inflation over the subsequent six months. The bottom graph is a percentage change in the producer price index for a 12 month period.

There does appear to be a correlation, one that is stronger during some periods as compared to others (particularly the 70s and 80s, something I'll come back to). Jim Hamilton's implicit assumption is that causation goes from the top panel to the bottom panel. But is it possible that causation goes the other way, from producer price changes to consumer price changes, and thus reduction in the real rate of return?

Well, yes.

One clue is the tremendous volatility of real interest rates. True real interest rates are not that variable. Consider, for example, rates of return on inflation indexed treasury bills. Those rates don't exist for as long a time series as the top panel above, but for the time period that does exist, they are nowhere near as variable as Jim's series. The problem is that short term inflation measures are noisy, often driven by fluctuations in food and energy prices, and these fluctuations are not anticipated in advance. Only expected changes in inflation should get priced in the real rate.

Second, much of volatility of in the producer price index--whatever the fundamental source--gets passed along to the consumer price index. So, say there's an embargo of oil from Iran and oil prices spike. We'll eventually see that in retail prices and the CPI. The price spike in turn causes the real interest rate to decline. So, there's good reason to think causation goes from the bottom graph to the top graph, rather than vice versa. That is, almost surely, what's going on in the 70s and 80s, which is where the link is strongest. I'd venture to guess that's the main source of correlation throughout.

So, in a nutshell, I'm not worried about the effect of QE2, or generally low or negative interest rates, on commodity prices. If commodity prices go up, I think that will mainly be a symptom of demand growth, which would be a good thing--a sign of recovery--for aggregate economies. Alternatively, prices could go up from real supply shocks and/or trade restrictions, which would obviously be bad things. But whatever may happen to prices, I think QE2 will be a very small deal.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...

-

It's been a long haul, but my coauthor Wolfram Schlenker and I have finally published our article with the title of this blog post in th...