Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Sugar, obeseity and a possible regression discontinuity design

Here is a random research idea that may be crazy. But maybe not. Either way, I really haven't the time to investigate it seriously. Maybe someone else does have the time.

The idea is inspired by two recent things: (1) Tuesday's seminar by David Just of Cornell University, who does research on the intersection of psychology and economics and is currently doing some interesting work on framing and package sizes; and (2) an intriguing article by Gary Taubes who investigates whether sugar is toxic. Taubes is mainly following arguments made by Robert Lustig, a Professor of Pediactrics at UCSF who has an influential YouTube video "Sugar: The Bitter Truth" (nearly 900,000 views--yikes!). That's a 90 minute tribe explaining Lustig's argument for why sugar is *the* culprit in the obesity crisis.

Lustig is pretty strident. Shrill? Regardless, I find his arguments compelling. This is not a quack idea.

Anyway. The theory still needs smoking gun evidence and that is going to be difficult to construct. And we all know there are extraordinary financial interests that will work hard to keep a tight lid on this if does turn out to be true. Corn, ADM, all manner of food processors, etc. It will be hard to obtain funding to do the experimental trials necessary to prove whether or not sugar is in fact toxic.

Are there any natural experiments worth exploiting?

Maybe.

By most accounts, the largest source of sugar is from sugary drinks, particularly soft drinks. Consumption has steadily increased and, at least in the aggregate data, seems to roughly match the obesity crisis. A lot of the growth in consumption must have come about from growth in the sizes of cup and bottle sizes. Years ago a "Coke" came in an 8oz. glass bottle. Later it was 10 oz. And then a 12 oz. can. Doesn't that seem quaint in this era of Double Big Gulp? Speaking of Big Gulps: the first super-sized soft drink at 7-11 convenience stores was in 1980, not long before obesity in the U.S. started its steep rise. But all of this is just anecdotal evidence.... Lots of other things have changed since the 80s.

What might be interesting, if the data can be obtained, is to exploit discrete changes in drink sizes that have taken place over time, and see if these discrete changes are associated with unusually large increases in the incidence of weight gain and diabetes. To do this well would require very large databases of weight, BMI, and/or incidence of diabetes, coupled with detailed data on drink package sizes over time. It would be especially helpful new larger drink sizes were introduced in different places at different times, or if one could exploit demographic or other kinds of variations. The nice thing about changes in drink sizes is that they are discrete and oftentimes large. This could be helpful because the largest possible confounding variable may be changes in consumption of meat or fat. I imagine changes in consumption of fat and meat were relatively smooth by comparison. Unlike food, a few food chain and soft drink companies (e.g. Coke and Pepsi) dominate the market, and sizes and size changes seem relatively uniform, and sometimes large.

The biggest challenge would be to amass the data for such an exercise. But if enough of the right data could be found, such an analysis might provide some powerful evidence, one way or the other.

The idea is inspired by two recent things: (1) Tuesday's seminar by David Just of Cornell University, who does research on the intersection of psychology and economics and is currently doing some interesting work on framing and package sizes; and (2) an intriguing article by Gary Taubes who investigates whether sugar is toxic. Taubes is mainly following arguments made by Robert Lustig, a Professor of Pediactrics at UCSF who has an influential YouTube video "Sugar: The Bitter Truth" (nearly 900,000 views--yikes!). That's a 90 minute tribe explaining Lustig's argument for why sugar is *the* culprit in the obesity crisis.

Lustig is pretty strident. Shrill? Regardless, I find his arguments compelling. This is not a quack idea.

Anyway. The theory still needs smoking gun evidence and that is going to be difficult to construct. And we all know there are extraordinary financial interests that will work hard to keep a tight lid on this if does turn out to be true. Corn, ADM, all manner of food processors, etc. It will be hard to obtain funding to do the experimental trials necessary to prove whether or not sugar is in fact toxic.

Are there any natural experiments worth exploiting?

Maybe.

By most accounts, the largest source of sugar is from sugary drinks, particularly soft drinks. Consumption has steadily increased and, at least in the aggregate data, seems to roughly match the obesity crisis. A lot of the growth in consumption must have come about from growth in the sizes of cup and bottle sizes. Years ago a "Coke" came in an 8oz. glass bottle. Later it was 10 oz. And then a 12 oz. can. Doesn't that seem quaint in this era of Double Big Gulp? Speaking of Big Gulps: the first super-sized soft drink at 7-11 convenience stores was in 1980, not long before obesity in the U.S. started its steep rise. But all of this is just anecdotal evidence.... Lots of other things have changed since the 80s.

What might be interesting, if the data can be obtained, is to exploit discrete changes in drink sizes that have taken place over time, and see if these discrete changes are associated with unusually large increases in the incidence of weight gain and diabetes. To do this well would require very large databases of weight, BMI, and/or incidence of diabetes, coupled with detailed data on drink package sizes over time. It would be especially helpful new larger drink sizes were introduced in different places at different times, or if one could exploit demographic or other kinds of variations. The nice thing about changes in drink sizes is that they are discrete and oftentimes large. This could be helpful because the largest possible confounding variable may be changes in consumption of meat or fat. I imagine changes in consumption of fat and meat were relatively smooth by comparison. Unlike food, a few food chain and soft drink companies (e.g. Coke and Pepsi) dominate the market, and sizes and size changes seem relatively uniform, and sometimes large.

The biggest challenge would be to amass the data for such an exercise. But if enough of the right data could be found, such an analysis might provide some powerful evidence, one way or the other.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

What crop supply response looks like

The other day I asked where the new cropland was going to come from.

Today we have William Neuman reporting:

But if farmers overuse the land today at the expense of future productivity, they may live to regret it. Prices could be high next year too. And the year after that. A little extra care today could yield even greater profits tomorrow.

Today we have William Neuman reporting:

When prices for corn and soybeans surged last fall, Bill Hammitt, a farmer in the fertile hill country of western Iowa, began to see the bulldozers come out, clearing steep hillsides of trees and pastureland to make way for more acres of the state’s staple crops. Now, as spring planting begins, with the chance of drenching rains, Mr. Hammitt worries that such steep ground is at high risk for soil erosion — a farmland scourge that feels as distant to most Americans as tales of the Dust Bowl and Woody Guthrie ballads. ...

...Now, research by scientists at Iowa State University provides evidence that erosion in some parts of the state is occurring at levels far beyond government estimates. It is being exacerbated, they say, by severe storms, which have occurred more often in recent years, possibly because of broader climate shifts...The article is a little short on quantitative facts. But it's pretty clear that incentives are strong to clear land to try to take advantage of high prices. And since marginal land tends to be more erodible, there will be more erosion.

But if farmers overuse the land today at the expense of future productivity, they may live to regret it. Prices could be high next year too. And the year after that. A little extra care today could yield even greater profits tomorrow.

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Shouldn't we be taxing gas more heavily?

I was lucky to be able to attend part of the NBER workshop on Environmental and Energy Economics at Stanford last week.

My favorite was a talk by Michael Anderson of UC Berkeley. He spoke about a paper joint with Max Auffhammer, also of UC Berkeley:

"Vehicle Weight, Highway Safety, and Energy Policy"

Sorry, no link. The issue is one that's been talked about many times: an arms race in vehicle weight and safety. The essential problem is that the heavier my vehicle, the safer it is for me and the more dangerous it is for you. Now, if we could all commit to smaller lighter cars, we'd pay less for our cars, have better gas mileage, and beno little less safe [please excuse my exaggeration], since when it comes to car-on-car collisions, it's mainly relative size that matters.

This sets up a classic prisoner's dilemma in which it's smart for one and dumb for all to buy bigger, heavier vehicles.

That basic tension is pretty well known, I think. What Anderson and Auffhammer did was measure, with apparent extraordinary accuracy, the size of the external cost of extra vehicle weight. That is, they estimated how much more likely someone is to die in a car accident if the opposing vehicle weighs a little more. I'm going from memory here, but I recall the number was something like a 50% increase in the odds of fatality for a 1000 lb. increase in vehicle weight. They estimated this using a huge database of actual vehicle-on-vehicle collisions and the estimate seemed amazingly robust. (Still, I need to read the paper...)

Using EPAs measure for the value of a statistical life (something like $5.8 million/life) and information on vehicle mileage, there were able to convert that weight externality into a near-equivalent gasoline tax. That tax didn't exactly match an appropriate tax on weight, but it turned out to be extremely close.

The take home number: $1/gallon.

That's a huge number. Before this study the conventional wisdom among transportation economists was that the largest driving-related externality was congestion, at something like $0.55/gallon. Pollution externalities, including CO2, come in at about $0.33/gallon. These are rough numbers from my recollection.

Can we start taxing gas more heavily already? It's not as if we don't need the revenue.

My favorite was a talk by Michael Anderson of UC Berkeley. He spoke about a paper joint with Max Auffhammer, also of UC Berkeley:

"Vehicle Weight, Highway Safety, and Energy Policy"

Sorry, no link. The issue is one that's been talked about many times: an arms race in vehicle weight and safety. The essential problem is that the heavier my vehicle, the safer it is for me and the more dangerous it is for you. Now, if we could all commit to smaller lighter cars, we'd pay less for our cars, have better gas mileage, and be

This sets up a classic prisoner's dilemma in which it's smart for one and dumb for all to buy bigger, heavier vehicles.

That basic tension is pretty well known, I think. What Anderson and Auffhammer did was measure, with apparent extraordinary accuracy, the size of the external cost of extra vehicle weight. That is, they estimated how much more likely someone is to die in a car accident if the opposing vehicle weighs a little more. I'm going from memory here, but I recall the number was something like a 50% increase in the odds of fatality for a 1000 lb. increase in vehicle weight. They estimated this using a huge database of actual vehicle-on-vehicle collisions and the estimate seemed amazingly robust. (Still, I need to read the paper...)

Using EPAs measure for the value of a statistical life (something like $5.8 million/life) and information on vehicle mileage, there were able to convert that weight externality into a near-equivalent gasoline tax. That tax didn't exactly match an appropriate tax on weight, but it turned out to be extremely close.

The take home number: $1/gallon.

That's a huge number. Before this study the conventional wisdom among transportation economists was that the largest driving-related externality was congestion, at something like $0.55/gallon. Pollution externalities, including CO2, come in at about $0.33/gallon. These are rough numbers from my recollection.

Can we start taxing gas more heavily already? It's not as if we don't need the revenue.

Monday, April 11, 2011

What if subprime and CDOs never happened?

I was watching the Inside Job for the other sleepless night (great movie by the way, both substantively and artistically), and I had a thought about the whole bubble and financial crisis that had not really occurred to me before. It's also a point that I think has been generally overlooked in commentary thus far.

First, some context:

Inside Job does a fine job spelling out the history of deregulation, development of CDOs and growth of the AAA bond market. They also do a really nice job explaining how CDOs worked and ultimately failed and the blatant corruption of the bond rating agencies. These features account for how financial markets were able to innovate new securities in an effort satisfy a nearly unquenchable thirst for low risk assets.

The movie basically blames Greenspan for low interest rates. But if Greenspan was at fault, it was only in that he didn't use the Fed's portfolio to help quench the world's thirst for safe assets. Consider, however, the size of AAA bond market and how much it grew between 2000 and 2008. I don't have the specific numbers in front of me, but it was in the tens of trillions of dollars. The Fed's balance sheet at the time was only about 800 billion. Yeah, maybe the Fed should have tried to increase rates a bit by selling some of its portfolio. But even the Fed was small relative to the demand forces at play.

It's that demand side that gets too little billing in the movie Inside Job. That demand side is the focus of an excellent radio story from This American Life that was broadcast on NPR. (You can listen here--note this was first broadcast before Lehman Brothers collapse and the ensuing crisis). The giant pool of money derived mainly from booming China and oil producing countries, aided partly by China's currency manipulation, which continues to this day.

Okay, that's the background. Now here's my thought of the moment:

What if there wasn't any funny business on the part of the banks and wall street? What if CDOs were regulated all along and we never had a boom in subprime lending and liar-loan mortgages with unverified income? Well, the basic economics tells us that the supply of AAA bonds would have been a lot less than it was. Which, in turn, means that the price of the AAA bonds would have been bid up even more than they were. Which, in turn, means that higher-risk bonds would also have been bid up to a higher price. Which means that interest rates would have fallen to a lower level--probably a significant lower level--than they had already fallen. And with interest rates falling even lower people with suitable credit would have wanted to buy even bigger houses. And people with suitable credit would have been even more tempted to take out even larger home equity lines of credit. And home prices would have kept going up. And so "the bubble," such as it was, almost certainly would have happened anyway.

The best example of this is Canada, where banking didn't get out of control but home prices still boomed. But unlike the US and much of the rest of the world, prices there haven't fallen much either. To the extent that they have fallen, it's probably due to the near collapse of the world economy, not Canadian problems.

Anyway. While all the shenanigans exposed in Inside Job boils my blood as much as the next guy or gal, I think the economic forces at play were even larger than the movie suggests.

Update: I changed the title to something more appropriate.

First, some context:

Inside Job does a fine job spelling out the history of deregulation, development of CDOs and growth of the AAA bond market. They also do a really nice job explaining how CDOs worked and ultimately failed and the blatant corruption of the bond rating agencies. These features account for how financial markets were able to innovate new securities in an effort satisfy a nearly unquenchable thirst for low risk assets.

The movie basically blames Greenspan for low interest rates. But if Greenspan was at fault, it was only in that he didn't use the Fed's portfolio to help quench the world's thirst for safe assets. Consider, however, the size of AAA bond market and how much it grew between 2000 and 2008. I don't have the specific numbers in front of me, but it was in the tens of trillions of dollars. The Fed's balance sheet at the time was only about 800 billion. Yeah, maybe the Fed should have tried to increase rates a bit by selling some of its portfolio. But even the Fed was small relative to the demand forces at play.

It's that demand side that gets too little billing in the movie Inside Job. That demand side is the focus of an excellent radio story from This American Life that was broadcast on NPR. (You can listen here--note this was first broadcast before Lehman Brothers collapse and the ensuing crisis). The giant pool of money derived mainly from booming China and oil producing countries, aided partly by China's currency manipulation, which continues to this day.

Okay, that's the background. Now here's my thought of the moment:

What if there wasn't any funny business on the part of the banks and wall street? What if CDOs were regulated all along and we never had a boom in subprime lending and liar-loan mortgages with unverified income? Well, the basic economics tells us that the supply of AAA bonds would have been a lot less than it was. Which, in turn, means that the price of the AAA bonds would have been bid up even more than they were. Which, in turn, means that higher-risk bonds would also have been bid up to a higher price. Which means that interest rates would have fallen to a lower level--probably a significant lower level--than they had already fallen. And with interest rates falling even lower people with suitable credit would have wanted to buy even bigger houses. And people with suitable credit would have been even more tempted to take out even larger home equity lines of credit. And home prices would have kept going up. And so "the bubble," such as it was, almost certainly would have happened anyway.

The best example of this is Canada, where banking didn't get out of control but home prices still boomed. But unlike the US and much of the rest of the world, prices there haven't fallen much either. To the extent that they have fallen, it's probably due to the near collapse of the world economy, not Canadian problems.

Anyway. While all the shenanigans exposed in Inside Job boils my blood as much as the next guy or gal, I think the economic forces at play were even larger than the movie suggests.

Update: I changed the title to something more appropriate.

Friday, April 1, 2011

Where's the land?

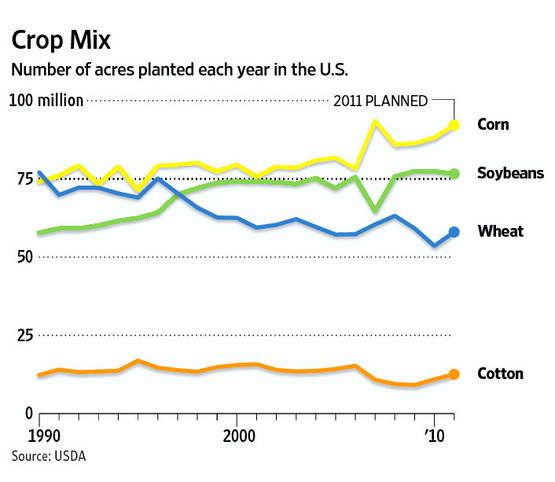

Corn, wheat and cotton plantings are anticipated to go up, and soybeans down just a smidgen. That's not too surprising given how high prices are.

But where's the land coming from? According to USDA, the net increase for these (the four largest cash crops besides hay) will be about 10 million acres. That's nearly one third the size of North Carolina. Notice in the graph that increases for one crop are typically offset by losses in another. Most hay land isn't going to be suitable for these crops.

Two wild guesses:

1) Prospective plantings are a little too optimistic

2) The Conservation Reserve Program is going to have a hard time enrolling much land in its signups this year.

But I don't think these two things can account for 10 million acres.

But where's the land coming from? According to USDA, the net increase for these (the four largest cash crops besides hay) will be about 10 million acres. That's nearly one third the size of North Carolina. Notice in the graph that increases for one crop are typically offset by losses in another. Most hay land isn't going to be suitable for these crops.

Two wild guesses:

1) Prospective plantings are a little too optimistic

2) The Conservation Reserve Program is going to have a hard time enrolling much land in its signups this year.

But I don't think these two things can account for 10 million acres.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

It's been a long haul, but my coauthor Wolfram Schlenker and I have finally published our article with the title of this blog post in th...

-

This morning's slides. I believe slides with audio of the presentation will eventually be posted here . Open publication - Free pub...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...