The infamous quote from Milton Friedman was: "We're all Keynesians now."

Some, including Friedman, claimed that quote was taken out of context. I can't find the precise quote right now, but he prefaced that statement with something along the lines of "in a sense.." and appended that comment with something along the lines "and in another sense none of us are Keynesians now."

What Friedman meant at that point in time, and I believe he thought up until the day he died, was that the vast majority of economists were Keynesians in the positive sense. That is, the Keynesian model of macroeconomic business cycles was essentially correct. But Friedman disagreed with Keynes' normative solution to the problem of severe recessions and depressions: that fiscal stimulus should be used to rescue the economy from recessions and depressions when interest rates hit the zero lower bound. Instead, Friedman argued that appropriate management of the money supply (i.e, Fed policy) would correct the problem of severe recessions and thereby render fiscal stimulus unnecessary.

And I think most economists agreed with Friedman on both points.

Until now. (Err.., almost two years ago.)

The current severe recession pokes hard at this old debate because the Fed did all the things Friedman said the Fed should do, but despite these efforts, the economy is still in a liquidity trap--stuck at the zero lower bound of short-term interest rates with high, persistent unemployment and anemic growth.

I had hoped that this situation might give rise to renewed and thoughtful intellectual debate about (a) what more could and should the Fed do in a situation like this one; and (b) what kinds of fiscal stimulus would make the most sense if it had to be done.

Sadly, we haven't had much of this kind of debate. Instead, I think the slap in the face that current events have given to economic thinking since Friedman's infamous quote seems to have caused a knee-jerk descent into denialism. One hand of that denialism has been to reject Keynesianism altogether, even the positive part that was more-or-less settled(**). The other hand of that denialism has been to assume there is nothing or very little the Fed can do if stuck at the zero lower bound. This wouldn't be so bad if the implications of this denialism were left in the ivory towers of academia. Sadly, it hasn't; it's infected both fiscal and monetary policy in ways that almost surely have and will continue to make our economic situation a lot worse than it needs to be.

Now it's true that blame on the denailism front goes to both sides of political spectrum. But it's also true that one side deserves a heck-of-a-lot more blame than the other. I think I'll leave it at that.

A critical issue here is, I think, that many who reject Keynesianism (in the positive sense) either (a) don't understand the essence of the model and/or (b) think of Keynesianism in purely normative terms (i.e., fiscal stimulus) and not in positive terms. Keynesianism is strange and in many ways counterintuitive, especially to students subject to standard undergraduate and graduate training. Yes, most 1st-year undergraduate textbooks have the standard Keynesian model. But I gather most students in most classes don't understand what they're reading, if they're reading. This stuff is too weird and most people are too impatient to figure it out. And most graduate students are neck deep in the mathematics of real business cycle theory and Neo-Keynesianism that they don't see the forest through the trees.

Anyway.

One issue that confuses a lot of people about Keynesianism (and Friedmanism) is one that stumped me really badly but I was too shy and perhaps lazy to ask a professor to explain it to me. I was always puzzled by the idea that the Fed lowered interest rates to increase the money supply, but that an increase in the money supply increased inflation (and thus interest rates). Now, all this is true and completely consistent with both Keynesian theory and with the facts. But it deeply confuses a lot of people, including one very accomplished economist who is President of one of the Federal Reserve banks.

Along these lines, I really like these two wonkish posts by Krugman [1, 2]. I think this kind of analysis is pretty much textbook and very few could substatively disagree. But I've never seen this particular issue laid out so clearly.

This kind of stuff is important because a lot of the people who reject Keynesianism just don't get the *positive* aspects of Keynesianism. Rather, it seems, they have a belief system that objects deeply to the normative Keynesian perscription (fiscal stimulus). It makes it hard to have an effective debate, or find serious solutions to real and challenging problems, when one half is thinking of Keynesianism in the fully positive sense and the other half is thinking of Keynesiansim in the fully normative sense, and there are few even acknowledging that fact that everyone is talking past each other.

My one complaint about Krugman here is that he should have been using his exceptional communication skills at pushing more action by the Fed a long time ago. After all, he's way more likely to influence the views of economists than those of congress and the President.

It seems the only person out there channeling Milton Friedman is Scott Sumner, and that's really too bad.

(**) Since Lucas's critique of Keynes there has been active research considering the fundamental sources of price stickiness, but none of these change the essential Keynesian story. There's also the Austrians (a relatively small fringe group), who channel Hayek, but are model phobic and tell stories that, save for their logical inconsistencies, seem fundamentally Keynesian in nature. Krugman [1, 2, 3] calls Austrians "self-hating Keynesians." I think he's right.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Bad Eggs

Given the theme of this blog, I feel obligated to write something about the big salmonella egg recall. I guess I've been slow to comment because in some ways it seems like an old story and I really don't have any special insights.

Given the theme of this blog, I feel obligated to write something about the big salmonella egg recall. I guess I've been slow to comment because in some ways it seems like an old story and I really don't have any special insights.Every now and then some kind of infectious disease gets into our food system wreaks

So, what should we do? Well, I think there are a lot potential solutions to the problem. I also think those solutions will probably happen more-or-less automatically. First, folks in the egg business are not going to be happy about the turmoil caused one or two bad corporate eggs. Producers may welcome and profit from better enforcement of regulations and steeper punishments for those who violate regulations. Second, there is a powerful movement against confined livestock operations happening in both Europe and here. This movement has way more legs than I ever thought it would and could lead to substantial changes in chicken and other livestock businesses. While all this could make some kinds of food more expensive, and this could hurt some lower-income families, I rather expect we'll see more of what we've already been seeing: more specialization and heterogeneity in the quality of food. Third, the Obama administration has already boosted funding for FDA, which tends to be more of an enforcement agency than USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service. Historically, more funding was going to USDA than FDA and FDA just didn't have the resources to enforce regulations (a form of starving the beast?) Fourth, I think technological solutions to the problem of

It's a shame we need to have a crisis before our system responds adequately to risks like these. But when a crisis does happen, I think our system does respond quickly. And I think even mass-produced eggs from confined operations can be safe and inexpensive. The institutions just need some refinement so that products are more traceable and bad actors can be held accountable

My old employer, USDA ERS, has a lot of good information on these issues.

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Blagojevich probability problems

Lunch break (for math/probability/statistics wonks):

So 11 of 12 jurors thought Blagojevich was guilty of selling a seat in the U.S. Senate. Assuming those jurors were a representative sample of the kind of jurors we might expect from a retrial, what are the odds he would be convicted if he were retried?

I see two ways of answering this question, one is pretty easy and the other, which has a Bayesian flair to it, is more difficult. The two answers are probably pretty similar, but I haven't done the harder and probably more appropriate one yet.

I'll post my answers later in the day. In the meantime, if you're up for a fun distraction you can tell me your answer in the comments.

Update: So the easy answer is obtained by assuming the probability of a "guilty" verdict juror is the frequentist estimate of 11/12, since in our sample of 12 jurors, one voted "not guilty." Then the probability of getting twelve "guilty" verdict jurors is (11/12)^12 = 0.352, or a 35.2% chance of conviction. Now that assumes a lot (I'll say more about assumptions at the end). But for now let's note that a frequentist would actually object to this answer because he/she would say that the true probability is unknowable, and thus would only say that the true probability of conviction on a retrial is between (9/12)^12 and (12/12)^12, or 3.2% and 100% with 95% confidence, which is not a very inspiring prediction.

So the only reasonable way to come with an actual probability of conviction on a retrial is to be a Bayesian. That means plugging in a "prior belief" for the odds of a randomly selected "guilty" voting juror before the first trial took place. Such a belief is subjective, which is philosophically problematic. But can't we come up with a reasonable, albeit subjective, prior? Or consider a range?

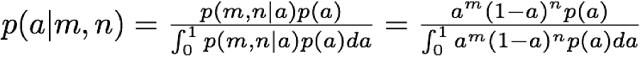

First, let's put down the key equation, which can be derived by combining the probability distribution of the binomial with Bayes rule, and is also given here on Wikipedia.

The notation here: p(a | m, n) is the distribution of the probability an individual juror will vote "guilty" given we have observed m of n jurors vote "guilty" in the first trial. So, m=11 and n=12. If we know p(a | 11, 12), we can calculate the probability of a guilty verdict on retrial as:

All we need now is p(a), the prior belief of a "guilty" voting juror, plug it into the Bayes relationship to find p(a|11,12), then solve the integral.

One commonly used prior is to assume a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. If you're not used to Bayesian analysis, this may seem strange, as we're assigning a probability distribution to a probability. That prior seems like a bad one here, because the prosecutors wouldn't have wasted their time on the initial trial if they weren't at least reasonably confident of a conviction. And if the prior belief of a guilty juror were uniform on (0,1), then the odds of conviction on the first trial would have been:

Which seems too small. So, how about we assume a prior distribution p(a) that would put the prior probability of conviction at 0.5. Yes, this is a wild assumption, but seems like a good starting point. Now with this one restriction we'll need a simple distribution with one parameter. A simple one is a polynomial distribution of the form p(a) = (z+1)a^z. If we select z such that

then it must be that z=11. So, plug all this in and it gives us a posterior probability of conviction equal to:

Or 43.8% chance of conviction on a retrial.

Now, if there weren't enough assumptions already, here are a few more. All of this assumes the retrial will be more or less like the initial trial, with a similar draw of jurors and the same presentation of evidence and defense.

But absent all of that, this geekish doodling suggests odds of conviction on the retrial look pretty similar, and perhaps slightly less, than they were perceived to be initially, at least if the initial belief of conviction was greater than 35% or so.

Wasn't that fun?

So 11 of 12 jurors thought Blagojevich was guilty of selling a seat in the U.S. Senate. Assuming those jurors were a representative sample of the kind of jurors we might expect from a retrial, what are the odds he would be convicted if he were retried?

I see two ways of answering this question, one is pretty easy and the other, which has a Bayesian flair to it, is more difficult. The two answers are probably pretty similar, but I haven't done the harder and probably more appropriate one yet.

I'll post my answers later in the day. In the meantime, if you're up for a fun distraction you can tell me your answer in the comments.

Update: So the easy answer is obtained by assuming the probability of a "guilty" verdict juror is the frequentist estimate of 11/12, since in our sample of 12 jurors, one voted "not guilty." Then the probability of getting twelve "guilty" verdict jurors is (11/12)^12 = 0.352, or a 35.2% chance of conviction. Now that assumes a lot (I'll say more about assumptions at the end). But for now let's note that a frequentist would actually object to this answer because he/she would say that the true probability is unknowable, and thus would only say that the true probability of conviction on a retrial is between (9/12)^12 and (12/12)^12, or 3.2% and 100% with 95% confidence, which is not a very inspiring prediction.

So the only reasonable way to come with an actual probability of conviction on a retrial is to be a Bayesian. That means plugging in a "prior belief" for the odds of a randomly selected "guilty" voting juror before the first trial took place. Such a belief is subjective, which is philosophically problematic. But can't we come up with a reasonable, albeit subjective, prior? Or consider a range?

First, let's put down the key equation, which can be derived by combining the probability distribution of the binomial with Bayes rule, and is also given here on Wikipedia.

The notation here: p(a | m, n) is the distribution of the probability an individual juror will vote "guilty" given we have observed m of n jurors vote "guilty" in the first trial. So, m=11 and n=12. If we know p(a | 11, 12), we can calculate the probability of a guilty verdict on retrial as:

All we need now is p(a), the prior belief of a "guilty" voting juror, plug it into the Bayes relationship to find p(a|11,12), then solve the integral.

One commonly used prior is to assume a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. If you're not used to Bayesian analysis, this may seem strange, as we're assigning a probability distribution to a probability. That prior seems like a bad one here, because the prosecutors wouldn't have wasted their time on the initial trial if they weren't at least reasonably confident of a conviction. And if the prior belief of a guilty juror were uniform on (0,1), then the odds of conviction on the first trial would have been:

Which seems too small. So, how about we assume a prior distribution p(a) that would put the prior probability of conviction at 0.5. Yes, this is a wild assumption, but seems like a good starting point. Now with this one restriction we'll need a simple distribution with one parameter. A simple one is a polynomial distribution of the form p(a) = (z+1)a^z. If we select z such that

then it must be that z=11. So, plug all this in and it gives us a posterior probability of conviction equal to:

Or 43.8% chance of conviction on a retrial.

Now, if there weren't enough assumptions already, here are a few more. All of this assumes the retrial will be more or less like the initial trial, with a similar draw of jurors and the same presentation of evidence and defense.

But absent all of that, this geekish doodling suggests odds of conviction on the retrial look pretty similar, and perhaps slightly less, than they were perceived to be initially, at least if the initial belief of conviction was greater than 35% or so.

Wasn't that fun?

Monday, August 16, 2010

Sunday, August 15, 2010

There is no such thing as free lunch (or parking)

Exquisite Tyler Cowen in the New York Times today, about how we pay much too little for parking. Parking isn't really free, but when we pay nothing for the marginal use of a parking space, it causes us to use land, cars, and generally structure our whole lives in grossly inefficient ways.

His article was inspired by a book by Donald Shoup.

So, this reads like an advocacy piece for higher parking fees and, perhaps implicitly, market pricing of everything. Okay, I might be able to get behind that.

But the more interesting question is, why is parking so often free?

First, I'd like to point out that when parking costs get really expensive the price does go up. I know some prime parking spots in DC can cost $50,000, and $25,000 is commonplace. Some parking spaces in Manhattan cost more than houses do in other parts of the country.

So, the free parking we're talking about is also the parking that generally tends to be less costly to provide. Yes, I also imagine that parking is implicitly subsidized via regulations and building codes. But the problem with presenting the story in this way is that it paints the free parking space as a kind of conspiracy concocted by those evil government interventionists.

I expect it's a lot more complicated. When parking is inexpensive, and almost everyone would be willing to pay the price anyway, the transactions costs of paying can get to be pretty high. It just isn't worth it to set up a mechanism for charging each person each time.

Now, if you're in a generally low-cost environment like this, and the collective interests decide it's not worthwhile to charge for parking and instead fold the costs in somewhere else, it tends to raise new issues that can be a pain to deal with. For example, a new condominium complex or new office building may open up and decide it might shirk its responsibility for parking provision. After all, it can simply free-ride on the "free" street parking or that provided by other buildings nearby. Thus, it's not surprising that regulations crop up that force new developments to provide parking.

The most egregious free parking situations are probably those in areas that have experienced rapid development. LA, where Shoup lives, developed in a inexpensive parking environment where free parking may have been the most efficient organizational arrangement. Then rapid population growth and congestion followed, and the opportunity costs of parking spaces went way up, making free parking a real problem. It can take a long while for the institutions to catch up with the new high-cost parking environment.

With any organizational structure there are costs and benefits. I rather like the idea of charging more for parking more often. But before we can seriously, honestly, deal with these problems we need to understand and be clear about the source of these crazy regulations. In the beginning they probably weren't so crazy. I'm just saying that some plain acknowledgment of that history, rather than a steady drum beat of free market ideology, might be more effective at pushing policy in the right direction.

His article was inspired by a book by Donald Shoup.

So, this reads like an advocacy piece for higher parking fees and, perhaps implicitly, market pricing of everything. Okay, I might be able to get behind that.

But the more interesting question is, why is parking so often free?

First, I'd like to point out that when parking costs get really expensive the price does go up. I know some prime parking spots in DC can cost $50,000, and $25,000 is commonplace. Some parking spaces in Manhattan cost more than houses do in other parts of the country.

So, the free parking we're talking about is also the parking that generally tends to be less costly to provide. Yes, I also imagine that parking is implicitly subsidized via regulations and building codes. But the problem with presenting the story in this way is that it paints the free parking space as a kind of conspiracy concocted by those evil government interventionists.

I expect it's a lot more complicated. When parking is inexpensive, and almost everyone would be willing to pay the price anyway, the transactions costs of paying can get to be pretty high. It just isn't worth it to set up a mechanism for charging each person each time.

Now, if you're in a generally low-cost environment like this, and the collective interests decide it's not worthwhile to charge for parking and instead fold the costs in somewhere else, it tends to raise new issues that can be a pain to deal with. For example, a new condominium complex or new office building may open up and decide it might shirk its responsibility for parking provision. After all, it can simply free-ride on the "free" street parking or that provided by other buildings nearby. Thus, it's not surprising that regulations crop up that force new developments to provide parking.

The most egregious free parking situations are probably those in areas that have experienced rapid development. LA, where Shoup lives, developed in a inexpensive parking environment where free parking may have been the most efficient organizational arrangement. Then rapid population growth and congestion followed, and the opportunity costs of parking spaces went way up, making free parking a real problem. It can take a long while for the institutions to catch up with the new high-cost parking environment.

With any organizational structure there are costs and benefits. I rather like the idea of charging more for parking more often. But before we can seriously, honestly, deal with these problems we need to understand and be clear about the source of these crazy regulations. In the beginning they probably weren't so crazy. I'm just saying that some plain acknowledgment of that history, rather than a steady drum beat of free market ideology, might be more effective at pushing policy in the right direction.

Friday, August 13, 2010

Arnold Zellner, a classic Bayesian

It took me an embarrassingly long time to fully understand the difference between Bayesian and frequentist views of probability. I don't think I fully appreciated the Bayesian perspective until I got to listen to Arnold Zellner, who spent his emeritus years at my alma mater, UC Berkeley ARE, when I was in graduate school there.

I only interacted with him personally a couple of times, and then only very briefly, but was often privy to his comments and questions during seminars. I found it interesting how he combined passionately strong views with an amazingly kind and gentle demeanor.

From Andrew Gelman's blog:

I only interacted with him personally a couple of times, and then only very briefly, but was often privy to his comments and questions during seminars. I found it interesting how he combined passionately strong views with an amazingly kind and gentle demeanor.

From Andrew Gelman's blog:

Steve Ziliak reports:

I [Ziliak] am sorry to share this sad news about Arnold Zellner (AEA Distinguished Fellow, 2002, ASA President, 1991, ISBA co-founding president, all around genius and sweet fellow), who died yesterday morning (August 11, 2010). He was a truly great statistician and to me and to many others a generous and wonderful friend, colleague, and hero. I will miss him. His cancer was spreading everywhere though you wouldn't know it as his energy level was Arnold's typical: abnormally high. But then he had a stroke just a few days after an unsuccessful surgery "to help with breathing" the doctor said, and the combination of events weakened him terribly. He was vibrant through June and much of July, and maintained an 8 hour work day at the office. He never lost his sense of humor nor his joy of life. He died at home in hospice care and fortunately he did not suffer long.From the official announcement from the University of Chicago:

Arnold began his academic career in 1955 at the University of Washington, Seattle, then moved to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 1966 he joined the faculty of Chicago Booth and remained on our faculty until his retirement in 1996.

Arnold pioneered the field of Bayesian econometrics and was highly regarded by colleagues in his field. He founded the International Society of Bayesian Analysis, served in numerous leadership roles of the American Statistical Association, and received several honorary degrees. His teaching also was recognized by the McKinsey Award for Excellence in Teaching. He remained active after his retirement, continuing to do research, publish papers, and serve as a mentor to students.

Arnold was a distinguished researcher, award-winning teacher, and wonderful colleague. His friendly greeting and gracious manner will be missed. We are fortunate to have had someone as remarkable both professionally and personally as Arnold be a member of our community for so many years. His legacy reminds us what makes this institution such a special place.Zellner was an old-school Bayesian, focusing on statistical models rather than philosophy. He also straddled the fields of statistics and econometrics, which makes me think of some similarities and differences between these sister disciplines.

To a statistician such as myself, econometrics seems to have two different, nearly opposing, personalities. On one side, econometrics is the study of physics-like laws--supply and demand, utility theory, simultaneous equation models, all sorts of attempts to capture economic behavior with mathematical laws. More recently, some of this focus has moved to agent-based modeling, but it's still the same basic idea to me: serious mathematical modeling. The data are there to understand the fundamental underlying economic processes.

But there's another side to economics, a side that I think has become much more prominent, and that's the anti-modeling approach, the distribution-free methods that try to assume as little as possible (replacing distributional assumptions by second-order stationarity, etc.) to be able to make forecasting or causal claims as robustly as possible.

To the extent that economics is a model-centered field, I think it's naturally Bayesian, and Zellner's methods fit in well. To the extent that economists are interested in robust, non-model-based population inference, I think Bayesian methods are also important--nonparametric methods get complicated quickly, and Bayesian inference is a good way to structure that complexity.

Unfortunately, Bayesian methods have a bad name in some quarters of econometrics because they are associated with subjectivity, which goes against both mainstream threads in econometrics. Whether you're doing physics-influenced modeling or statistics-influenced nonparametrics, you want your inferences to be objective as possible. So both kinds of econometricans can agree to disdain Bayes.

What Zellner showed in his work was how Bayesian methods could be objective, and statistically efficient, and solve problems in econometrics. This was, and is, important.

P.S. I only met Zellner a few times and did not know him personally. My only Zellner story comes from the famous conference at Ohio State University in 1991 on Bayesian Computation via Stochastic Simulation. At one point near the end of the meeting, Zellner stood up and said: Hearing all this important work makes me (Zellner) realize we need to start a crash research program on these methods. And you know what they say about crash research programs. It's like trying to create a baby by getting nine women pregnant and waiting one month. (pause) It might not work, but you'll have a hell of a time trying. (followed by complete stunned silence)

The other thing I remember about Zellner was his statistics seminar at the business school, which I attended a few times during my semester visiting the University of Chigago. No matter who the speaker was, Zeller was always interrupting, asking questions, giving his own views. Not in that aggressive econ-seminar style that we all know and hate; rather Zeller always gave the impression of being a participant in his seminar, one among many who just had the privilege of being able to speak whenever he had a thought--which was often. He was lucky to have the chance to express his statistical thoughts in many venues, and we as a field were lucky to be there to hear him.

Inflation targeing, it's way past due

I can't believe I was naive enough to write this 15 months ago:

So, while I vigorously applaud Krugman's column today, I also think it is long past due. Inflation targeting may have been Krugman's idea in the first place, but as a cure for our current malaise, he has written very little about it until recently. Instead he wrote mostly about fiscal policy, and most of what he said about monetary policy was that it simply couldn't work at the zero lower bound. There were subtle caveats here and there, but these were way too nuanced for all but the most informed readers.

Now if Ben did his helicopter business 18 months ago maybe things wouldn't be so dismal today. As it stands, I rather expect another six to 12 months of frittering around before policy gets serious, and another six to 12 months before it starts hitting the economy. For those who have already been unemployed for six months or more, that's an awful lot of unnecessary misery.

But then that whole idea kind of fell off the table pretty quickly. I've lamented this a few times in the past.Finally we have direct talk of inflation targeting

While I'm no macroeconomist, I've read a lot of good macroeconomists, and this has made me question why explicit inflation targeting backed by unconventional monetary policy was not on the table like six months ago.

Better late than never. Here are excerpts from the story at Bloomberg.

What the U.S. economy may need is a dose of good old-fashioned inflation. So say economists including Gregory Mankiw, former White House adviser, and Kenneth Rogoff, who was chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. They argue that a looser rein on inflation would make it easier for debt-strapped consumers and governments to meet their obligations. It might also help the economy by encouraging Americans to spend now rather than later when prices go up.I predict: rational expectations macro will die a slow death and we will have a revival of monetarist vs. Keynesian debate. This debate has been bubbling beneath the surface but it hasn't been in sharp focus. I think that is about to change. The center of the debate will concern the optimal balance of fiscal policy and inflation targeting backed by unconventional monetary policy when faced with a liquidity trap.

“I’m advocating 6 percent inflation for at least a couple of years,” says Rogoff, 56, who’s now a professor at Harvard University. “It would ameliorate the debt bomb and help us work through the deleveraging process.” ...

....Even after all the Fed has done to stimulate the economy, some economists argue that it needs to do more and deliberately aim for much faster inflation that would also lift wages.

With unemployment at a 25-year high of 8.9 percent.... Wages and salaries rose 0.3 percent in the first quarter, the least on record...

In advocating that the Fed commit itself to generating some inflation, Mankiw, 51, likens such a step to the U.S. decision to abandon the gold standard in 1933, which freed policy makers to fight the Depression

Update: Up until now the debate has seemed unfocused and scattered because some sides seem wedded to vanquished ideas. There are the Libertarian types who seem split between the Andrew Mellon liquidationists who believe government should do nothing except watch the bankruptcies unfold (and maybe go back to the gold standard) and the Friedman monetarists, who seem to believe monetary policy and perhaps small regulatory changes are all that's needed, but often slip into saying fiscal stimulus is counterproductive. Then there are new Keynesians who seem to think there should be both fiscal and monetary stimulus, but don't write much about monetary policy, and have been mum about inflation targeting. Nevertheless, I think the Keynesians strongly support new, unconventional monetary policy and inflation targeting.

Even if we ignore the liquidationists, too much of the debate is about silly ideas, like fiscal stimulus being counterproductive. I think you can be against fiscal stimulus without saying it is counterproductive. The argument would be that more vigorous monetary policy coupled with an explicit inflation target might be enough, and thereby make fiscal stimulus unnecessary. This may be a tough sell, but the Fed policy, while vigorous, has fallen far short of the kind of inflation targeting proposed by Rogoff. Then the Keynesians would have to retort with more nuanced arguments about the optimal balance of fiscal and monetary policy. Instead, the left spends all their time pointing and shrilling at the crazy claims made from the right.

If leading thinkers on both sides, from Mankiw-Romer types on the right to Krugman-Delong types on the left, all think inflation targeting is a good idea, then they should be saying so loud and clear.

So, while I vigorously applaud Krugman's column today, I also think it is long past due. Inflation targeting may have been Krugman's idea in the first place, but as a cure for our current malaise, he has written very little about it until recently. Instead he wrote mostly about fiscal policy, and most of what he said about monetary policy was that it simply couldn't work at the zero lower bound. There were subtle caveats here and there, but these were way too nuanced for all but the most informed readers.

Now if Ben did his helicopter business 18 months ago maybe things wouldn't be so dismal today. As it stands, I rather expect another six to 12 months of frittering around before policy gets serious, and another six to 12 months before it starts hitting the economy. For those who have already been unemployed for six months or more, that's an awful lot of unnecessary misery.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Is there excess volatility in commodity prices?

I've had a number of relatively technical posts, a couple recently, about behavior of commodity prices. It's because I'm generally wondering if there is excess volatility in commodity prices, much like Robert Shiller and others have long pointed out about the behavior of stock prices and housing prices.

As astute readers may have noticed, I really don't have a strong opinion on this yet. At this point I don't see any smoking-gun evidence that commodity prices display anything but rational market behavior. But the amount of volatility we do see suggests that both supply and demand are very inelastic, and/or policies and trade restrictions facilitate what are, in effect, very inelastic supply and demand.

There is one exception. While I haven't studied it as closely, gold prices are looking an awful lot like a bubble to me.

As astute readers may have noticed, I really don't have a strong opinion on this yet. At this point I don't see any smoking-gun evidence that commodity prices display anything but rational market behavior. But the amount of volatility we do see suggests that both supply and demand are very inelastic, and/or policies and trade restrictions facilitate what are, in effect, very inelastic supply and demand.

There is one exception. While I haven't studied it as closely, gold prices are looking an awful lot like a bubble to me.

Extreme heat is still bad for corn and soybeans

Bloomberg:

Update: Current temperatures. They are still rising fast. If this keeps up for a few more days I'd say yields will get hammered.

Corn futures rose the most in almost two weeks and soybeans gained on speculation that the recent Midwest heat wave will mean smaller production than the record crops predicted today by the government.

August has gotten off to the second-warmest start since 1960, T-Storm Weather LLC said today in a report. Another forecaster, Commodity Weather Group LLC, said about 25 percent of the U.S. soybean-growing area won’t get enough rain for proper plant development over the next two weeks, and that the dryness could harm a third of the Midwest should rain miss sections of Illinois this weekend, as expected.

“The crops are going downhill rapidly in parts of the Midwest and South,” said Mark Schultz, the chief analyst for Northstar Commodity Investment Co. in Minneapolis. “Our farmers are already preparing for corn yields that may fall 5 percent to as much as 10 percent from earlier field samples.”

Update: Current temperatures. They are still rising fast. If this keeps up for a few more days I'd say yields will get hammered.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Yes, we're looking more like Japan every day

Deflation here we come. I'm glad I moved to long-term treasuries:

At today's close:

U.S. Treasuries:

3-Year: 0.79

5-Year: 1.45

7-Year: 2.13

10-Year: 2.76

30-Year: 4.01

I think the only way to stop this slide is extremely aggressive monetary and/or fiscal policy. I don't think that's going to happen.

So, how low will rates go?

My armchair guess is that 10-year treasuries will fall below 2.0 percent before this is over. But I really don't know.

At today's close:

U.S. Treasuries:

3-Year: 0.79

5-Year: 1.45

7-Year: 2.13

10-Year: 2.76

30-Year: 4.01

I think the only way to stop this slide is extremely aggressive monetary and/or fiscal policy. I don't think that's going to happen.

So, how low will rates go?

My armchair guess is that 10-year treasuries will fall below 2.0 percent before this is over. But I really don't know.

Commodity price variability and supply/demand responsiveness (wonkish)

The other day I wrote about how a classic puzzle in the academic literature on commodity prices has apparently been solved in a nice paper by Cafiero et al. The puzzle concerned an apparent excess autocorrelation in commodity prices and the solution was rather technical. It turned out that approximation errors in the statistical calibration of that model, not the theory itself, led to the puzzle. A better calibration by Cafiero and coauthors led to a model with much more inelastic demand that also fit the price data well.

But on a deeper level I think some puzzles remain. The model traditionally used in the commodity price/storage literature is one with a steep consumption demand curve and a vertical, perfectly inelastic supply curve that shifts horizontally with the weather. Production shocks are buffered by a competitive storage market that buys and stores commodities when prices are low and sells when prices are high.

For explaining price behavior, it is somewhat arbitrary whether it is demand, supply or both that respond to price. The point is that both supply and demand must respond in a very inelastic manner else prices would not be so variable and not so autocorrelated. Or at least that's my strong hunch.

This brings me to a totally separate literature on commodity supply response. At least for agricultural commodities this literature is quite substantial and most supply elasticity estimates center around one, which means production doubles if prices double, all else the same. If you look more closely at the literature, it's clear that supply elasticities bounce all over the place and in the most careful studies supply is far less elastic. So maybe we shouldn't take that literature too seriously. (Sometimes I wonder if the elasticities center around one because that seems like a safe, referee-pleasing number. Anyway...)

But what I haven't seen anyone articulate very clearly is a huge apparent disconnect between what the commodity price/storage literature has to say and what the supply literature has to say. If the only way to get commodity prices to fluctuate as much as they do and to be as autocorrelated as they are is to have *both* supply and demand be very inelastic, then most of the supply response literature must be very wrong. Or, if it's not wrong, and supply is even somewhat responsive to price, then the price puzzles of too much volatility and too much autocorrelation creep back into the picture. Alternatively, one might make some strange assumptions about the costs of storage. But those assumptions would be so strange, I believe, that they would be broadly deemed implausible.

My own number crunching with Wolfram Schlenker suggests supply is in fact quite inelastic, but still about twice as responsive as demand. Taken together, I still find the elasticities large enough that I have a hard time seeing how and why prices could be so volatile and autocorrelated in a well-functioning competitive market with storage. But I haven't done a full-blown analysis to check.

The recent activity in wheat prices, and the crazy behavior of rice in 2008, has me thinking that uncertainty about policy--like export bans--is an important part of the picture. These could build in a market expectation of a more inelastic supply and demand responses than we might otherwise expect.

Update: An important piece of the underlying intuition here is that the physical size of the shocks--physical quantity of stuff that actually pushes prices up or down--tends to be very small relative to the size the related price spikes. Take Russian wheat shortage, for example--it's really not that big of a shock relative to the world wheat market. With storage buffering these tiny shocks, we just shouldn't be getting that much in the way of price movements. But we are. And I still don't think we in academia have a very clear explanation for why this is the case.

But on a deeper level I think some puzzles remain. The model traditionally used in the commodity price/storage literature is one with a steep consumption demand curve and a vertical, perfectly inelastic supply curve that shifts horizontally with the weather. Production shocks are buffered by a competitive storage market that buys and stores commodities when prices are low and sells when prices are high.

For explaining price behavior, it is somewhat arbitrary whether it is demand, supply or both that respond to price. The point is that both supply and demand must respond in a very inelastic manner else prices would not be so variable and not so autocorrelated. Or at least that's my strong hunch.

This brings me to a totally separate literature on commodity supply response. At least for agricultural commodities this literature is quite substantial and most supply elasticity estimates center around one, which means production doubles if prices double, all else the same. If you look more closely at the literature, it's clear that supply elasticities bounce all over the place and in the most careful studies supply is far less elastic. So maybe we shouldn't take that literature too seriously. (Sometimes I wonder if the elasticities center around one because that seems like a safe, referee-pleasing number. Anyway...)

But what I haven't seen anyone articulate very clearly is a huge apparent disconnect between what the commodity price/storage literature has to say and what the supply literature has to say. If the only way to get commodity prices to fluctuate as much as they do and to be as autocorrelated as they are is to have *both* supply and demand be very inelastic, then most of the supply response literature must be very wrong. Or, if it's not wrong, and supply is even somewhat responsive to price, then the price puzzles of too much volatility and too much autocorrelation creep back into the picture. Alternatively, one might make some strange assumptions about the costs of storage. But those assumptions would be so strange, I believe, that they would be broadly deemed implausible.

My own number crunching with Wolfram Schlenker suggests supply is in fact quite inelastic, but still about twice as responsive as demand. Taken together, I still find the elasticities large enough that I have a hard time seeing how and why prices could be so volatile and autocorrelated in a well-functioning competitive market with storage. But I haven't done a full-blown analysis to check.

The recent activity in wheat prices, and the crazy behavior of rice in 2008, has me thinking that uncertainty about policy--like export bans--is an important part of the picture. These could build in a market expectation of a more inelastic supply and demand responses than we might otherwise expect.

Update: An important piece of the underlying intuition here is that the physical size of the shocks--physical quantity of stuff that actually pushes prices up or down--tends to be very small relative to the size the related price spikes. Take Russian wheat shortage, for example--it's really not that big of a shock relative to the world wheat market. With storage buffering these tiny shocks, we just shouldn't be getting that much in the way of price movements. But we are. And I still don't think we in academia have a very clear explanation for why this is the case.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Battle of the Paul's

That's Paul Ryan Paul vs. Paul Krugman

(Oops. Very sorry. Maybe my jet lag made me dyslexic. If it's any consolation, a lot of people call me Robert instead of Michael).

Krugman says Paul Ryan'sPaul's math doesn't add up. Math (and facts) don't usually matter in political debates, and I suspect that is true here as well. But on factual grounds I'd say the second guy with the given name Paul has utterly eviscerated the other.

The budget situation isn't complicated. It's mainly about medicare and taxes. In the long run we have to cut one, increase the other, or some balance of these two. Obama's health care bill has possibly made some modest gains on the Medicare side of things. We'll see. The rest is chump change.

Now Libertarians and most Republicans most of the time are for much larger cuts in Medicare, or even dismantling Medicare altogether. This is one way to cut spending for real. But since it isn't politically popular to say that, they often disguise these positions.

The problem is, we just can't have honest policy debates when blatant lies are called "intellectually audacious" and receive glowing, uncritical coverage by the Washington Post.

Just sayin'.

(Oops. Very sorry. Maybe my jet lag made me dyslexic. If it's any consolation, a lot of people call me Robert instead of Michael).

Krugman says Paul Ryan's

The budget situation isn't complicated. It's mainly about medicare and taxes. In the long run we have to cut one, increase the other, or some balance of these two. Obama's health care bill has possibly made some modest gains on the Medicare side of things. We'll see. The rest is chump change.

Now Libertarians and most Republicans most of the time are for much larger cuts in Medicare, or even dismantling Medicare altogether. This is one way to cut spending for real. But since it isn't politically popular to say that, they often disguise these positions.

The problem is, we just can't have honest policy debates when blatant lies are called "intellectually audacious" and receive glowing, uncritical coverage by the Washington Post.

Just sayin'.

Post doctoral position looking into the effects of climate change on food price variability

Do you have a PhD in economics or a related field, love to crunch numbers, and have an interest in how climate change will affect world agricultural markets? Come work with David Lobell, myself and Wolfram Schlenker!

What we're working on is nicely illustrated by the current situation with wheat prices (see the last post). We're hoping to hire someone quickly, probably well ahead of the formal job market.

You can find the job posting here. It will go up on JOE relatively soon.

Let us know ASAP if you're interested.

What we're working on is nicely illustrated by the current situation with wheat prices (see the last post). We're hoping to hire someone quickly, probably well ahead of the formal job market.

You can find the job posting here. It will go up on JOE relatively soon.

Let us know ASAP if you're interested.

Was the wheat price spike caused by the weather or the export ban?

The weather has been terrible in Russia this year: too hot and too little precipitation. This has led to widely reported increases in wheat prices as well as higher prices for corn, soybeans, rice and other food staples. A couple days ago wheat prices went up more than six percent in one day as Russia announced it would stop exports in an attempt to keep domestic wheat prices from getting too high. This of course led to higher price for the rest of the world and possibly export bans in other countries.

This, I think, illustrates some of the worry about climate change and agricultural production. These kinds of policy responses, and indeed much of agricultural policy in general, tends to come along in response to extreme events. Some and perhaps most of these knee-jerk policies, like export bans, tend to make the problem worse.

Now we can all emphatically argue that countries shouldn't ban exports in response to a crisis. But the reality is that these kinds of responses will happen just as they always have happened. So if climate changes brings about these kinds of episodes more frequently, or generally causes greater uncertainty as agricultural production shifts to new regions, we can probably expect more price spikes and more hunger in the poorest food-importing countries. Greater variability in production and uncertainty about policy responses will also cause speculators to rationally store more grains. While greater storage will help to buffer the greater uncertainty, by holding inventories at greater levels greater uncertainty can also cause prices to be higher on average, even if average total production is unaffected by climate change.

It is just these issues I'm starting work on with David Lobell and Wolfram Schlenker.

This, I think, illustrates some of the worry about climate change and agricultural production. These kinds of policy responses, and indeed much of agricultural policy in general, tends to come along in response to extreme events. Some and perhaps most of these knee-jerk policies, like export bans, tend to make the problem worse.

Now we can all emphatically argue that countries shouldn't ban exports in response to a crisis. But the reality is that these kinds of responses will happen just as they always have happened. So if climate changes brings about these kinds of episodes more frequently, or generally causes greater uncertainty as agricultural production shifts to new regions, we can probably expect more price spikes and more hunger in the poorest food-importing countries. Greater variability in production and uncertainty about policy responses will also cause speculators to rationally store more grains. While greater storage will help to buffer the greater uncertainty, by holding inventories at greater levels greater uncertainty can also cause prices to be higher on average, even if average total production is unaffected by climate change.

It is just these issues I'm starting work on with David Lobell and Wolfram Schlenker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...