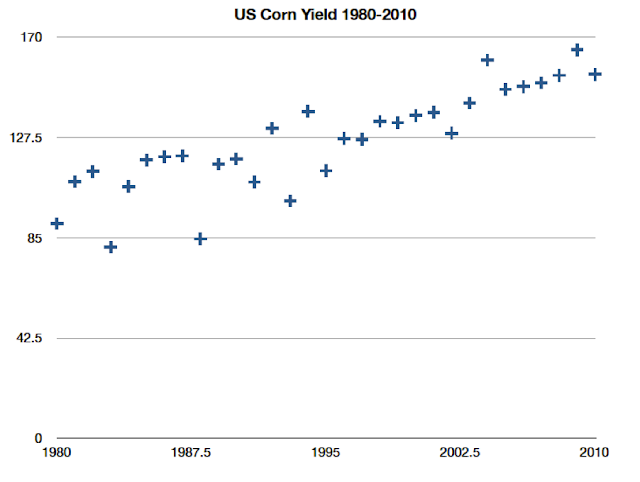

This is a super simple plot of yields from the world's most successful crop: US corn.

Yields have been trending up in steady linear fashion for a long time. The last five years are a continuation of that trend.

But consider: Prices were at an all time low, in real terms around 2005-2006, trading at less than $2 bushel, and they have been above $4/bushel most of the time since late 2007. That's a solid doubling or more of prices for a sustained period of time.

Now, if yields respond a lot to prices, shouldn't we see some kind of acceleration in the trend? After all, prices were pretty much falling through most of the period from 1980 to 2005, and since then have increased substantially.

Like I said the other day, I sure don't "see" a big price effect on yields. Do you?

There's a lot more data where this came from at www.nass.usda.gov

Note that I usually don't believe "statistical significance" that cannot be seen with a compelling graphical presentation of the data.

Oh, and fertilizer was pretty cheap last year, too.

Update: Sorry, I've been out of commission for awhile and not checking the ol' blog. I concur with James Giese's points about fertilizer use and the trend in yields. I've played around with these data a lot, most of it unpublished. That experience tells me that one cannot reject the null hypothesis that yields are a trend from breeding and genetic improvement plus random weather variations.

The "right" amount of fertilizer is key, and too much can sometimes be a bad thing, not just for the water, but also for yields.

One side point: From an economic perspective, it is often optimal for farmers to"over" apply fertilizer vis-a-vis the agronomic maximum. This is basically a gamble that the weather will turn out in such a way to make use of that extra fertilizer, even though it often won't. From the vantage point of farmers' profits, the economic downside of applying too much agronomically is small compared to the extra profits if the weather is such that the extra fertilizer is actually needed by the plant. This is an important point made by Babcock and others way back in the 80s I think. This has nothing to do with "risk aversion" as sometimes described in the literature, but rather the option value associated with the possible high marginal productivity of fertilizer. Now, given all the literature on "too much" fertilizer use, we should be pretty skeptical about a big fertilizer-induced yield response to price.

The anonymous commenter--who suggests that land expansion may be driving down average yield when prices go up--may have a point. This is something we are exploring. I'll just say for now that this kind of effect, though long hypothesized, is very hard to see in the data. While there is a clear acreage response to price, it is a small one. And especially for corn, that acreage margin isn't necessarily bad land. It's mainly diversions from soybeans and cotton--pretty high value stuff. So it's hard to see how this influences the aggregate yield very much.

Finally: A graduate student has been trying to replicate Houck and Gallagher. So far not so good: He can't even get the same sign. We're missing some of the early data, but using the more current data that are available, the same regressions say yields decline with price. I think there are some tough statistical issues here that Houck, Gallagher, and the broader field have thus far neglected. Nevertheless, I've seen enough to be extremely skeptical of earlier findings.

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Scarcity and Strategic Trade of Rare Earth Minerals

China has a near monopoly on rare earth minerals used in all kinds of manufacturing. These kinds of commodities must have extremely inelastic demand. Thus, it's not surprising to see China, which possesses about 95% of know extractable deposits, curtailing exports.

Curtailing exports will raise prices on the amounts they do export, and also raise the international market value of goods produced in China using rare minerals. While some may interpret the action as a slight against free market fundamentalism, a much easier and more compelling explanation is that China is simply asserting its market power for nationalistic gain. To me, anyway, this looks like a textbook example of strategic trade.

Curtailing exports will raise prices on the amounts they do export, and also raise the international market value of goods produced in China using rare minerals. While some may interpret the action as a slight against free market fundamentalism, a much easier and more compelling explanation is that China is simply asserting its market power for nationalistic gain. To me, anyway, this looks like a textbook example of strategic trade.

Tuesday, December 28, 2010

How much do crop yields respond to commodity prices?

There's an old paper by Houck and Gallagher that examines how corn yields respond to price changes. They found corn yields went up 21 to 76 percent with a 100 percent increase in price, presumably a response to increase fertilizer use. In econ speak this is called an "elasticity" between 0.26 and 0.76. The total supply response would be this elasticity plus the land area response.

The middle estimates in that old paper are being used by some to justify relatively benign effects from ethanol policy on food commodity prices.

Some recent updates to that old work are finding numbers at the lower end of that range, but also find large acreage response elasticities. Those arguing for a big yield response acknowledge that the land response is small, around 0.1. But there are lots of folks saying that the overall, yield plus land area, supply response to price is between 0.5 and 1.

These results contrast sharply with my own work with Wolfram Schlenker. After accounting for endogeneity bias (which makes elasticities too small) we find the yield-plus-land elasticity to be around 0.1. It's also hard to reconcile a large supply response to some basic facts about commodity prices and production.

Consider:

(i) It's a truly global agricultural commodity market;

(ii) global production of agricultural commodities is very smooth (weather shocks mostly average out);

(iii) consumption is smoother than production due to storage ;

(iv) prices vary a LOT and are highly autocorrelated (a price shock sticks around for a long time), which is due mainly to (iii);

(v) prices change sharply, and persistently, in response small, transitory production shocks (e.g., bad weather or USDA forecast updates).

These facts tell me that both supply and demand must be very inelastic. If supply response were as elastic as 0.5, we just wouldn't get big, persistent price shocks in response to small weather surprises. This is because production shocks could be so easily smoothed with inventories and greater or lesser production in future time periods. Indeed, commodity price behavior by itself implies a total economic response (that's the supply elasticity plus demand elasticity) on the order of 0.2 or possibly much less (this can be traced to the famous work by Deaton and Laroque, or to more recent work by Cafiero et. al, that I've mentioned before on this blog).

Also, if you just look at yields, you will find they look like random noise (weather) around a linear trend. There's no autocorrelation there while there's a ton of autocorrelation in prices. I certainly can't "see" a big price response (although there may be a small one).

So, I'm super skeptical. I need to do more crunching to figure out how these folks are getting such crazy numbers. But there's something fishy here. These elasticities just don't add up to the stylized facts we all know well.

Cynical me is thinking about those economists who believe that all elasticities lie between 0.5 and 2, and so hunt around for a specification that gives them the answer they expect. Also, the real number is probably so small that it can't be estimated with statistical significance, which makes it difficult to publish. So, all we see in print are the big "statistically significant" numbers from badly specified models.

Update : There is also the problem with finding the mechanism for a large yield response to price. We have experimental data on yields in relation to fertilizer applications and yield simulation models put together by crop scientists. Both show a highly non-linear link between fertilizer and yield. That is, yields go up sharply with higher application rates up to a threshold, above which fertilizer has little or no marginal influence. The steepness of the yield/fertilizer link below the threshold suggests farmers will generally apply at near-threshold levels over a broad range of output prices (the threshold depends a bit on the weather, and weather effects output price, so statistics here can be tricky). Anyway, the point is that if farmers apply fertilizer at near yield-maximizing rates even when prices are pretty low, so it's hard to see how prices could cause a very large yield effect via fertilizer inputs, even though a modest effect is plausible.

Update : There is also the problem with finding the mechanism for a large yield response to price. We have experimental data on yields in relation to fertilizer applications and yield simulation models put together by crop scientists. Both show a highly non-linear link between fertilizer and yield. That is, yields go up sharply with higher application rates up to a threshold, above which fertilizer has little or no marginal influence. The steepness of the yield/fertilizer link below the threshold suggests farmers will generally apply at near-threshold levels over a broad range of output prices (the threshold depends a bit on the weather, and weather effects output price, so statistics here can be tricky). Anyway, the point is that if farmers apply fertilizer at near yield-maximizing rates even when prices are pretty low, so it's hard to see how prices could cause a very large yield effect via fertilizer inputs, even though a modest effect is plausible.

Monday, December 27, 2010

Commodity prices: scarcity bites

Today Krugman writes about commodity prices (oops, missed the link the first time). To me, anyway, he looks right on all counts.

1) I've seen no evidence that the spike in 2008 was a speculative bubble. That goes for the current fledgling rise as well.

2) I don't think the commodity prices bear significant influence on inflation. Most of what we buy is comprised of domestic wages and rent, neither of is likely to much influenced by commodity prices, so inflation will remain subdued.

I wonder if Julian Simon were alive today, whether he would be willing to make another bet with Paul Ehrlich. We'll never know. But if he were alive, and he were to repeat that bet, this time I think he'd lose.

1) I've seen no evidence that the spike in 2008 was a speculative bubble. That goes for the current fledgling rise as well.

2) I don't think the commodity prices bear significant influence on inflation. Most of what we buy is comprised of domestic wages and rent, neither of is likely to much influenced by commodity prices, so inflation will remain subdued.

I wonder if Julian Simon were alive today, whether he would be willing to make another bet with Paul Ehrlich. We'll never know. But if he were alive, and he were to repeat that bet, this time I think he'd lose.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Michael Oppenheimer on the role of scientists in policy

A transcript is below; video here. Hat tip to Ruben Lubowski and Climate Progress.

TRANSCRIPT:

I feel particularly honored to have been asked to deliver the first Stephen Schneider lecture. Steve was a friend and a colleague, and an inspiration, who spoke eloquently and convincingly about questions with which I have struggled for my entire career and which I am going to address today: What is a useful and proper role for scientists in the public arena? How can we best discriminate where the boundary lies between expert knowledge, and values or political opinion, and how can we properly honor that line? What can we expect in the way of reception for our interventions and how can we increase their efficacy?

At the same time, I feel a bit sheepish about this task, because I’m sure some of my recommendations will sound obvious and trite to you, like Polonius’ “to thine own self be true”, although hopefully not that trite. In addition, while I intend to keep war stories to a minimum, I am after all a practitioner of public involvement rather than an academic expert on it, so my own experience is most of what I have to offer and I hope that suffices. Finally, I’m sure I have violated some of the recommendations I am about to put forth many times, many times. Involvement in the public arena is complicated.

This talk is structured as follows: first, I raise three questions which might be asked by any of us who are skeptical about scientists becoming involved in the public arena. I hope my answers will convince you that such involvement is sensible and to some degree inevitable. Second, noting that such involvement doesn’t mean all of us aspire to become a Carl Sagan or a Jim Hansen, I’ll propose a couple of broad principles and five potential options for involvement, each quite distinct, along with some advice on how to navigate each. Third, I’ll strike four cautionary notes, emphasizing the difficulties you will encounter if you chose to “go public”. By way of wrapping up, I’ll channel some advice from Steve himself.

But let me begin by providing some scholarly context for understanding Steve’s philosophy of how scientists could, should, and actually do engage with the public. There is a substantial literature on these questions, going back to CP Snow and probably earlier, and more recently including the views of Naomi Oreskes, Sheila Jasanoff, and Roger Pielke, Jr. The dilemma highlighted by CP Snow provides both a convenient jumping off point for this lecture and also a useful way to understand why Steve Schneider’s views were so central to our current concerns. So let me remind you of Snow’s argument in his 1959 lecture The Two Cultures, which if you hadn’t heard before, you probably did hear about during last year’s 50th anniversary of the event, which generated a lot of discussion in the pages of this community’s publications.

Why dredge up CP Snow’s argument again? Partly because his statement of the science-society communications problem was so clear, but also because, in a broad sense, the key challenges for the human endeavor on which he believed science should focus, remain unresolved, have grown even more complex, and were also at the center of Steve Schneider’s professional career. Furthermore, and in hindsight, Snow’s proposed solutions to the communications problem were not sufficient to overcome the complexity of the communications terrain, and how to navigate this terrain is after all the main subject of this talk.

In The Two Cultures, Snow, a physicist and novelist, issued a diatribe against Britain’s educated elite of the 1950s which foreshadows with remarkable prescience today’s perceived crisis in the public’s supposed lack of understanding of science, and the potential consequences of this shortfall, particularly in debates over the environment. Peel away the class critique of The Two Cultures and a deep fear over the incapacity of people to comprehend, and of government to tackle, the key issues of global resources and global equity, is revealed, broadly the same debate we are in the midst of now and which so engaged Steve. This pessimism sits side by side with optimism about technological possibilities for fixing these problems, if only science were heeded and mobilized.

Snow identified the key problem but misjudged the solution by failing to anticipate the complexity of the current world. Snow based his analysis on a juxtaposition that no longer is valid: the culture of physics providing one model of influential thought, and high-brow culture providing the other. Today, the physics model for scientific progress, which I’ll caricature as neat laws describing everything imaginable, deduced by geniuses and verified or falsified by experiments, seems relevant to a smaller and smaller set of public issues. Gradually, the model is being replaced by the more complex and uncertain way of thought characteristic of problems in geosciences, biology and environment. In these arenas, fact and value are sometimes harder to separate; and so it is not coincidental that these fields generate many of today’s political conflicts as well. Furthermore, culture among the influential is no longer particularly high-brow, so generalist versus expert is probably a better description of the current dichotomy.

The quandary is this: How can a society of generalists govern itself when most of the issues of the day are highly technical? Many solutions to this conundrum have been proposed by scientists: one is Snow’s idea of merging the scientific and popular cultures through improved education; another is a public-policy technocracy dominated by scientific elites, in some ways, the French model. Of course, these proposals cover only half the existing spectrum of opinion. Some people of faith might argue that science’s role in people’s education and public decisions ought to be entirely secondary.

Specifically, Snow argued that the scientific revolution was the last phase of the industrial revolution, and he saw the industrial revolution as a mixed bag. It brought general improvement but wide disparities. Snow’s argument anticipated the rise of China, the shifting of the economic balance among nations, and the importance of the global implications of seemingly local problems, particularly the population problem. He imagined science, integrated into education and politics, as the font of all solutions. And he saw scientists as wiser, more reliably ethical, and more inclined to an optimistic and activist view of human possibilities, than are others.

What Snow could not have appreciated is the limitations of science in the face of the complexity of the problems he had highlighted, and the resulting existence of a contested zone where values, judgment, and science fight it out for controlling influence over policy decisions. He also seemed blind to the limited ability of scientists to explain their own work so that their role in public education was in fact problematic to implement. Some scientists are fearful of treading into the contested terrain at all, while others do so but experience great difficulty in distinguishing its boundaries, and separating expert knowledge from value-laden, subjective judgments.

These fears and difficulties should not be surprising: many scientists loathe ambiguity as a permanent state because it is their job, our job to resolve it. Inability to do so is seen by us as either failure, or that we are dealing with substance that is beyond our expertise. Scientists like to deal with problems by draining them of values and ambiguity, and isolating “the facts”, and I think this accounts for the limitations of Snow’s vision. Politics and policy must inevitably reinsert the latter complexities. Scientists are in their hearts control freaks, but control is simply not possible to exert over such problems.

The human complexity of dealing with these issues, which Snow overlooked, was Steve Schneider’s favorite playground. In other words, Steve was a CP Snow for the post-modern era.

I’ll return to Steve’s views at the end of my talk, after outlining the conundrum that scientists face in considering involvement in the public arena: first, by addressing why participation in the public arena can’t be easily avoided; next by suggesting some ideas, based on my own experiences, which may help you formulate your own guidelines so that you can better calibrate your own participation.

Involvement in the public debate over public policy is a common and accepted role for scientists in many disciplines. In the sciences related to public health, it’s taken for granted that experts will talk loudly in public about the implications of their research for public policy, whether in regard to smoking, or diet, or HIV. There is also a remarkable track record of geoscientists taking a lead role in the public arena, and actually affecting public policy, in directions that many of us are grateful for.

Sherry Rowland’s public role on ozone depletion stands out, as do the contributions of Jim Hansen, Steve Schneider, and Bob Watson on climate. In other arenas, one can point to Hans Bethe and Henry Kendall at one end of the belief spectrum, or Edward Teller at the other. Some of these people mostly translated science for the wider public, others endorsed specific policy initiatives. I agree with the views of many of these scientists, and strongly disagree with others. One cannot prove that the world followed a better, or even a different course, due to their interventions. But I think the quality of public discourse and the information reaching policy makers was better for their interventions, taken as a whole.

Despite such examples, Jim Hansen has asserted that by and large, members of our community are reticent, hesitant to speak out about the implications of their research, and when they do, they take a cautious approach. By and large, he’s probably right, and I too would like to see my colleagues have more to say because I think they (you) have a lot to offer. But it’s not easy to do so in a satisfying way; the messages are easily misunderstood; our interventions are sometimes unhinged from our expertise in a way that is not helpful to the listener (after all, reticence is sometimes the right choice). Also, it’s not clear when, who or if, anyone is listening.

Finally, I assume that this audience holds a spectrum of views on the particulars of any scientific problem, which, like global warming, is characterized by large uncertainty, and I invite those in the audience who might have disagreements with me, to pay attention anyway, because you may well chose to engage in the public arena, and if so, you will face the same problems as I do.

Still, a scientist who doubts the necessity of such involvement might ask the following questions:

Question 1: Public involvement takes time. Can’t I stay in my office or lab while policy-makers and the public wrestle over what to do about the various technological problems we face?

Alas, I’m afraid this is increasingly difficult to do and if followed by the community as a whole, would be highly irresponsible. Science is not wholly owned by governments but it does draw a large fraction of its support from governments. I’ll return to the question of individual ethical obligation a bit later. For now, let me just say that this financial support means that science as an enterprise, if not individual scientists, owes something in return: the least we can do is be available to interpret our research findings, and if possible, explain their implications for society. But there is also a pragmatic reason to get involved: If we do not, we leave Congress, for example with the option of seeking explanations from those less competent to offer these up. Alternatively, we can be proactive about it and define the meaning and significance of our own work, rather than letting others do it for us.

Perhaps, if policy were linearly related to science, abstinence would be a plausible approach.

Question 2: Can’t we just make clean, scientific statements in English, and leave it at that?

Even if we could make clear and direct explanations of our work absent ambiguity yet honoring all our beloved caveats, interaction with the public is a dialogue, not a monologue. Even the “cleanest” statements demand elaboration once the inevitable follow-up questions begin to role in.

Let me provide an example in the form of a famous statement in the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment report, a statement renowned and highlighted in the report for its clarity and simplicity: “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal”.

What precisely about warming is unequivocal: that it has been occurring? That it will occur in the future? That the entire problem we call “global warming” is unequivocal in all aspects?

These are all questions that a reasonably intelligent person could raise when reading such a statement unless they also absorbed the minutiae of explanations and modifications which accompanied it in the report. In fact, the UN climate negotiators recently tripped on this very issue when they wrongly asserted that the statement meant that not only the fact that earth had warmed, but the attribution of this warming to human activity were both unequivocal.

We cannot simply drop our pearls of wisdom and expect others to deconstruct them. That much is our job.

Every time we emphasize or de-emphasize a point, assign likelihood to an outcome or refrain from doing so, we are exercising expert judgment about what is important and what is not. Similarly, every time we say an outcome “may” happen rather than it “may not”, or that it’s opposite may or may not occur, we are making such judgments. And those judgments are partly subjective because in many cases a different expert might justifiably have a different view and express it differently. Uncertainty goes hand-in-hand with subjective judgments, and with the necessity of making them.

For an entertaining example of this point, I urge all of you to see the movie “Fair Game”, and listen closely to the scene where former vice presidential aide Scooter Libby explains to a CIA analyst why words like “maybe” and “maybe not” matter in expressing expert judgment.

Question 3: OK, I’ll acknowledge that someone has to do the dirty work, but I’m not so good at communication. So I’d prefer to let everyone else take this on.

Wrong again. Ask some of our colleagues who never tried to be public figures or never said anything even mildly controversial but who nevertheless became collateral damage in so-called Climategate, the CRU email episode, just because they were recipients of mostly anodyne emails, sent by others.

To be blunt, science and scientists are now part of an unavoidable and contentious public discussion. This is no longer 1983 when the National Academy of Sciences could issue a monumental report on climate change and have it go virtually unnoticed. Climate and related issues are characterized by very high socioeconomic stakes: that’s the main reason why so much research money (relatively) is spent on them and why they generate so much public controversy. That’s life as it is and as it will be, for the foreseeable future. We as a community and as individuals can either try to frame that discussion, and be prepared for involvement, or let others who are less interested in scientific truths set the terms of the public discussion.

I am encouraged that institutions like AGU are eager to do more to defend and explain science, and are puzzling over and experimenting with approaches for doing so. But it’s not the institutions per se that carry the weight. In the end, it’s up to the individuals who constitute them, YOU.

Question 4: Am I obliged to get involved?

As I noted already, I am sure that the community as a whole has an obligation to society to be informative about the meaning and implications of its research findings, assuming society wants to hear such information. I am confident in this view because I understand that the public, through the taxes it pays, supports a large portion of our research, including for many, our salaries. Surely, there is some obligation in return that goes beyond merely working away in our offices or laboratories. I feel strongly that the obligation on the community as a whole is implicit.

But what about our individual obligations? Any involvement means lost research time. There is a credible argument that the world is better off with most of us just doing research and foregoing involvement. Still, we can’t all be free-riders or our community would have fallen down on its overall obligation. For me, it’s enough that people, through their leaders, through the media, and through individual requests, want the information. I am happy to provide it. And if they want my judgment about what to do about these problems, then I will provide that too, and try to be clear about which is which. In the end, each of you needs to decide for him/herself.

But there are two related and less contentious aspects of this obligation at which our community is failing miserably. First, we do little if anything to advise young scientists on the social and ethical context of the world into which they are about to enter: what are the implications of their research for other human beings, what constitutes honest representation of their research beyond the rules of professional review and publication, how might others use their research and how should they think about this transaction? NSF now requires instruction in research ethics, but that only scratches the surface. Are there any major research universities that require graduate students in our fields to take courses which would give them a complete framework for thinking about the obligations I have discussed, or the public context in which their scientific views will be received, interpreted, and utilized?

Our second failure is the inadequacy of the response to threats to individuals in our community. Our professional societies respond vigorously to threat to the community as a whole, as when the federal research budget is reduced. But they have had great difficulty figuring out how to address such attacks on individuals, or whether they have a role to play at all. But this is sort of the inverse of the free-rider problem: the individual lamb can be sliced off from the group and devoured and the group can ignore it but eventually, the whole heard is cut to shreds. AGU, NAS, AAAS, and the rest of our professional organizations need to learn how to differentiate reasonable complaints which call for a due process approach that can strengthen our enterprise, like the establishment of the committee to review IPCC by the Inter Academy Council, from unreasonable, unfair, and abusive attacks, which if met with silence, threaten to undermine the independence of science.

I hope I have convinced you that participation in the public arena is both desirable and to some degree unavoidable. If so, what are your options for involvement? And what are sensible guidelines for behavior in this arena? Let me provide some suggestions, based on my own experiences. The taste for, aptitude for, and utility of involvement in the public arena varies widely from scientist to scientist. So let’s consider a wide range of options:

Option 1: You can very publicly take sides, for instance in an election, based specifically on what you see as the policy implications of your research.

This is one end of the spectrum, and many of us individually have publicly and loudly supported candidates, including Presidential candidates. In a less-noticed way, many scientists sign onto collective campaign endorsements. It is argued by some that there is a price to pay for such activity, but the only one I’ve seen is that it is likely to rule you out for a political appointment if your candidate loses. But if getting such a job is not your objective, then why worry? But clearly, this end of the spectrum is not to everyone’s taste.

Concern also comes from an entirely different direction: that visible participation by scientists qua scientist in the political process dilutes the credibility and independence of science. I don’t know if we have proof on the latter point either way, but I merely note that scientists have long taken partisan positions as individuals, and I know of no evidence that it has done any damage to our collective reputation. An analog in a different arena is provided by Eisenhower’s running for President which some argued would be problematic for the image of the military. Was it? Closer to home, was former Senator and Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist’s emphasizing his credentials as a doctor problematic? In both cases, I think not. What was problematic for Frist was when he departed from his sound expert judgment as a doctor and began to make implausible pronouncements which he backed by his credentials, i.e., his TV diagnosis of Terry Schiavo.

My ground-rule here is clear: if you are going to use scientific arguments as a rationale for taking partisan positions, make sure you aren’t simple using your science as a cover for what are really political, not scientific judgments. In other words, make sure you feel comfortable in your scientific skin.

Option 2: You can take sides publicly on the policy implications of your research, including actively lobbying for particular policy proposals (by visiting representatives in Washington, writing letters to the editor, posting blogs, etc., or just answering questions from the media).

Again, there is no reason not to participate in this way. Scientists do it all the time. The least controversial example in our community occurs when scientists testify on Capitol Hill in favor of additional research funding. This is surely a political act based on scientific, as well as other, judgments and motivations. More controversial interventions, but also with a long pedigree, occur when scientists back particular initiatives related to their scientific findings, for example cap-and-trade, or carbon tax, or fuel-economy standards. In my lifetime, it’s been done by Edward Teller or Henry Kendall on nuclear arms control, or various biologists on stem cell research, or Paul Ehrlich on family planning, or Gene Likens on acid rain, or dozens of the people in this room on climate change. The public discourse is richer for these interventions, not poorer.

But I also argue for caution here. My ground-rule (and most decidedly Steve’s) is this: the further from your expertise you wander in making judgments about policy, the shakier ground you are on, and the more humility and caution is called for. It’s one thing to argue that within scientific uncertainty, warming of a given amount would cause a particular level of damage. But it’s a value judgment, not a scientific one, to argue that emissions reductions which could avoid the damage are necessary. And it is far outside the expertise of most people in this room to assert that one or another type of policy initiative is appropriate for getting there.

I do not argue that one should avoid such value-judgments, but like Steve, I think it’s important to be clear in your own mind, and to the public, which sort of judgment you are making. We are all entitled to our value judgments, our personal risk assessments, and they should be a key factor in public policy. But we are not entitled to make value judgments or political or policy judgments in areas where we are not experts, like politics or economics, and try to pass them off as following automatically from our scientific expertise.

I would like to be able to say that we should stop speaking as experts when we venture into terrain where we feel uncomfortable as experts. But for some reason, this approach has not worked very well. Some of our colleagues seem unaware of where their expertise ends, and they haven’t been willing to do the hard homework necessary to extend their expertise enough to justify their positions.

There is one measure of expertise which, though conservative, is a good guideline: have you published in the field: I am trained in atmospheric chemistry but have taught myself and have published peer reviewed papers on glaciology, so I feel that I can speak to reporters as an expert on the role of ice sheets in sea level rise. But this wasn’t always the case: Fifteen years ago, I became concerned about the fate of the ice sheets. I wasn’t an expert on this subject, so I generally avoided commenting on whether the ice sheets were stable or not. After all, if you are a heart specialist, and someone asks your view on his kidney problem, should you answer the question, or tell them to consult a kidney specialist? The media can be lazy about doing due diligence in selecting whom to ask, but we shouldn’t be lazy in deciding whether to answer.

So, I did my homework, spending an entire year reading everything I could get my hands on about Antarctica and Greenland, going back to the literature from IGY right up to the present, and eventually publishing a review paper on the subject. I I felt qualified to make some judgments, publicly. But reporters are often rushed, and a scientist’s ego sometimes forecloses the option of handing off a media opportunity to a colleague.

Still, just because you’ve published in the peer review literature doesn’t mean you have a license to say whatever comes to mind on a subject, even about its scientific aspects. If you know your view on a scientific point is anomalous or incomplete, say so. Half-truths and statements out of context are sometimes the worst form of public deception. Being asked to venture expert opinions is intoxicating, but you need to keep your head while doing it. If someone sticks a microphone in front of you, it’s awfully hard to keep quiet, but sometimes that’s the right thing to do.

There’s another way to handle the issue of boundaries. If you know you’re passing the limits of your core expertise, and you still feel compelled to venture an opinion, perhaps in order to paint a complete picture, then rely on what IPCC has said, or what an NRC panel has said in addressing the issue. This problem always arises: for example, when experts in the physical climate try to add perspective by mentioning impacts or when impacts experts are tempted to discuss the comparative benefits of emissions abatement and adaptation. You needn’t keep mum, or give such a pinched answer that it’s useless to others. Instead, you can seek at least a modicum of comfort by relying on the “scripts” which assessments by these organizations have produced for our community. Even if it differs from your personal view, at least these assessments have a logic and a pedigree behind them.

Likewise, we are not entitled to assert or imply special status to our value judgments because they relate indirectly to areas of our expertise. If a doctor expressed a view on whether people subject to capital punishment via death by injection felt pain and suffered, we would tend to cede this terrain as within their expertise. But surely none of us would hesitate to express a value judgment about capital punishment in front of a doctor due to the doctor’s holding such expertise, nor would we necessarily honor the doctor’s judgment on whether capital punishment is ever justified. Likewise, we should not hesitate to express value judgments about matters bordering on our expertise, but neither should we expect others to accept our judgments as having any higher value than theirs. And we should not pretend our values are a necessary outcome of our expert understanding. Often, they are not.

Options 1 and 2 clearly involve advocacy, but you can eschew advocacy, and still participate usefully. You can do as IPCC does, and avoid forwarding particular policy positions. Indeed consider these options:

Option 3: You can simple talk to reporters, for instance offering useful insights into what is the state of the science, and what are its implications (as far as you know them).

But be aware of the point I made earlier: emphasis embodies subtle judgment, and there is a wide range of opinion about climate change once we get down into the details. As more of us speak in public, there will be more public disagreements on some issues. For example, some of you believe that collapse of the MOC, if the world undergoes a moderate warming, is a serious risk, while others don’t.

Some of you think the case for ice sheet instability is strong, others do not. IPCC has expressed views on this: some of us accept the IPCC view in general but not on particular details. While I am deeply committed to the IPCC process, I certainly disagree on some important judgments, not just the way they were communicated but on the substance, with regard to sea level rise for example. Regardless of the claims of some of our colleagues, IPCC is not a monolith and dominant views in our community are not enforced on others. What is frowned upon is not a divergent view, but the refusal to accept evidence-based arguments, the dishonest search for a back door when the front is block by overwhelming proof.

So be prepared for public disagreement, and welcome it. But also be prepared to call out the misuse of science or of stonewalling in the face of evidence.

And there is a price to pay in speaking with the media, even just to venture scientific judgments. You will receive some nasty emails (as I’ll discuss later), or worse. You will, to some extent, lose control of your time. Once you decide you are willing to speak with the media and your name appears in public, you will be called on more and more. At some point, everyone needs to draw some boundaries in order to get their day job done. But the media are fickle, and there will be times when you have something pertinent to say and no one will ask you. You need to be psychologically ready for that, too.

There are other complexities. Steve made a career of explaining how wrong the media can get the story, even when you say it clearly. But the flip side is also true: few of us know how to deliver a scientific statement correctly but in language that the average consumer of information can understand. Usually, it can be done, but not always. If in doubt, I would choose correct over clear. But having to make such a choice never feels good.

And if you are called out of the blue by the media, think things through before you answer. There is absolutely no reason to believe that your first thought is your best thought. The smartest answer I ever gave a reporter was “I’ll call you back”.

Option 4: You can participate in IPCC, AGU, AAAS, or other outreach activities.

There is safety in numbers, and also the opportunity to step back and facilitate direct interventions by others. This is a critical task for the community as a whole, the avenues are expanding, and if you feel more comfortable participating in this way, then that’s the route you should take.

Of course, there’s always

Option 5: One can choose not to comment on the science except to an academic audience, refuse to sit on an expert panel where your judgments can be widely disseminated, avoid talking to anyone else about controversial issues or even refuse to comment on an applied aspect of your research.

Alas, even then you are not “safe”. As the CRU email episode shows, these days to be immune from being dragged into the public arena, one has to avoid research in any area which might conceivable have an application in the real world, and unplug entirely to boot!

No matter which of the first four routes you choose, it’s important to maintain perspective because participation isn’t always very rewarding, often doesn’t produce a tangible product, and doesn’t automatically translate into effectiveness.

All that science and scientists can demand in our society is to set the stage for dealing (or not) with a problem. After that, we have a citizen’s right to express an opinion and some other citizens may think our opinions have special value due to our presumed understanding of the interface between science and policy. But other expertise, value judgments, and politics dominate the rest of the policy evaluation and action spectrum, so while we have a right to be annoyed and outraged if the science itself is distorted or lied about, we have no particular right as scientists to throw a temper tantrum if the policy outcome isn’t what we wanted it to be.

Furthermore, while the general public holds scientists in relatively high regard (not much competition), many are wary on the details. Amid the welter of a bad economy, unemployment, college tuition, illness, divorce, and who knows what else, along comes an “expert” telling you, “I have a magic black box, and out pops the answer and it says “if you don’t do X,Y, or Z, it’s the end of the world”. The automatic reaction is to disbelieve and rankle at such expert “command authority”. When a car mechanic or widget maker or doctor offers us a judgment, we demand explanations: why should scientists seek a special immunity due to their expertise? We are not a priesthood; we are fallible. We are just a contributor, albeit an important one, to a larger public discussion.

Based on these general points, here are some specific suggestions for using your time efficiently and effectively, while keeping your expectations aligned with potential outcomes:

1. Think about your audience in advance and be ready for people not to listen to, or not to hear your message.

Different audiences are receptive to different aspects of what you want to say, so always know whom you are speaking with and what your objective is. In particular, scientific arguments won’t always work, even one-on-one: receptiveness to expertise is selective, preconditioned by the listener’s views on a constellation of subjects.

Not surprisingly, recent research in social psychology, political science, and public opinion (and I note in particular the work of Skip Lupia of Michigan, Jon Krosnick of Stanford, and Tony Leiserowitz of Yale) indicates that the average citizen has limited interest or time for delving into technical subjects, whether health care reform, or nuclear arms control agreements, or global warming. Rather, they often look to the views of surrogate experts or opinion leaders who presumably have enough resources to evaluate and assess the relevant information, and make an informed judgment. But there are lots of potential surrogates on an issue like climate change, and people will often pick the one who aligns generally with their world view. Al Gore provides a noteworthy example. He did his homework and he had access to a big megaphone, so many peoples’ views on global warming were influenced by his, particularly those to the “progressive” side of the political center. But if he moved the meter with people on the right, it may have overall reinforced their skepticism, because they were attuned to other surrogates. Various biases of this sort operate from both ends of the spectrum and shape the uptake of technical information.

In other words, with many people, science is part of a world-view woven from many components. Discordant threads aren’t easily accommodated: often they are simply removed.

But the situation is not hopeless by any means. I’m a so-called progressive, but I have convinced more than a handful of very accomplished, smart, conservative and wealthy individuals to accept the scientific consensus on climate change. I did this by sticking to the science, and not giving them political or moral lectures. In fact, many of their political and moral principles are 180 degrees opposite mine, but they happened to be interested in the environment or conservation. Particularly if you feel you are on a moral crusade, you may feel such people are not your target audience and that’s fine. But if they are, you might consider putting aside the moral principles while you serve up the science. It is sometimes possible to accept the latter without agreeing on the former. We don’t all share the same values, and it might be more difficult to shift a person on both facts and values at once.

One of our problems today is that people only chat about subjects like this with people they already expect to believe them. Very possibly, you will make the biggest difference by speaking with others whom you know have a fundamentally different world view. If you disagree with the Wall Street Journal editorial representation of science, then take the opportunity when you’re in the same space as someone who probably reads those editorials to engage them, even if you think their general political values are vastly different. Make them doubt their view of the science; don’t hide yours. In other words, cocktail parties can be more important places for education than universities.

2. No matter how non-partisan and “scientific” is your intervention, expect to be vilified; but never return the favor.

Here are some excerpts from emails I received after recent TV or radio interviews; they are not the worst I’ve heard: for example, some of our colleagues have been recipients of direct threats, which I have not. But I hope these do help to inoculate you, should you decide to venture out into public:

“First of all I must say that you look like Bozo the Clown”, followed by vulgar references to my moustache.

“I suppose most of us can’t expect much from (VULGAR REFERENCE TO MY INFERRED ETHNIC BACKGROUND), like you. Except that you are so (EXPLECTIVE) ugly.”

Or the one with a subject line “Commie Maggot”:

“Commie Maggot ….. DIE SLOW, DIE HARD.”

Among the other risks you will encounter for “going public” is that you will be accused of misconduct and even subject to legal inquiry. Since Michael Mann, a victim of such attacks, is speaking tomorrow, I’ll leave this subject largely to him. But I want to note, as I alluded to before, that keeping your head low is no longer a guarantee of safety. For example, many of you know that earlier this year, Senator James Inhofe, acting as minority leader of the Senate Committee on Environmental and Public Works, published a list of 17 scientists who were “key players” in the “CRU controversy” and who “violated fundamental ethical principles governing taxpayer-funded research and, in some cases, may have violated federal laws”, then warning that “The next phase of the Minority’s investigation will explore whether any such violations occurred”.

The apparent criteria for winning a spot on the list are that you have been involved in IPCC and also received one of the thousands of stolen CRU emails (even if you never responded to any of them)! The list includes several scientists who are not known for making public pronouncements, and others who are beyond reproach, like our colleague Susan Solomon.

So there’s no use being intimidated and hiding rather than speaking your expert mind if you really want to do so. Ultimately, so-called “good behavior” may reduce your exposure, but won’t completely remove your vulnerability to the hazard.

3. Don’t hide your biases; think them over in advance and lay them out.

We all have them, explicit and implicit. I worked for an advocacy organization, EDF, for 21 years and I am still consulted for scientific advice by its staff. This relationship, like other consulting, brings along the possibility of conflict of interest when I make my judgments and express my views on certain subjects. I try hard to separate my judgments about policy matters from this relationship and I think I succeed. But I owe the listener the information so they can weigh its importance. Accordingly, the relationship is mentioned prominently on my CV, my bios, my web page. I urge all of you to be transparent about the existence of such relationships in your own professional lives.

But there are other biases, subjective ones, harder to identify and articulate. I discussed these a few minutes ago. There is no good answer to how to deal with these, except to be aware of the difference between facts and value judgments, to try to listening to yourself when you speak, and hear yourself as someone with a differing world view might hear you.

Years ago, I asked one colleague why he thought climate sensitivity was almost certainly closer to 1.5 degrees Celsius than three or four or five, as the NAS then had it. Rather than giving me physical evidence, he said he just didn’t believe that humans could affect the climate that strongly. That’s fine, but it’s a belief that should be stated at the outset, not hidden in the weeds.

4. Keep it civil; don’t let differences ruin collegiality

I’ve goofed a few times in my public utterances, and I try to learn from each mistake. After having briefed a high White House official in an administration long ago on the subject of ozone depletion, I described him to a reporter as “semi-ignorant” because he had made a naïve comment to me belittling the importance of the issue. When my remark was published in a major newspaper, an opportunity to further educate an influential leader had been lost to me, and I regret it to this day.

I once got into a figurative food fight on TV with a colleague, attacking each other rather than each other’s scientific assertions. You could hear the remote controls all over TV-land going click as viewers moved to another channel, and another educational opportunity was lost.

Science should be on the record; but ad hominem attacks are counterproductive and almost always out of order.

The worst outcome would be to sacrifice our norms due to the pressure; pressure not just from our enemies to keep quiet, but from our friends who are eager to solve the climate problem. Our norms are ours. They may evolve over time to accommodate the modern context, but their essence should be stable, and we should not sacrifice them for short term gain.

Over the next couple of years, each of us as individuals may need the collective “us” as a community more than ever. There may be more attacks, there may be more mistakes. But the worst outcome would be if we let these divide us as individuals, and at the same time, separate us from the very special norms and values which, as scientist, we all share.

Finally, let me close with some of Steve’s words, provided indirectly. I asked his wife and colleague, Terry Root, what Steve would have advised if he were giving this speech. This is what she told me, and if you slept through the past 45 minutes, this is really all you need to remember anyway:

1. The truth is bad enough

2. Integrity should never be compromised

3. Don’t be afraid to use metaphors

4. Distinguish when speaking about your values (as a member of the human race) and when speaking as scientist

5. Don’t let fear (of deniers) keep you from working on the most important problems facing society

Let me end with the way Steve ended many of his emails after relating one of his own experiences with the public arena and policy makers, a combination of exasperation and hope:

“!@#$%”…oh well”

….Stephen Schneider, often

TRANSCRIPT:

I feel particularly honored to have been asked to deliver the first Stephen Schneider lecture. Steve was a friend and a colleague, and an inspiration, who spoke eloquently and convincingly about questions with which I have struggled for my entire career and which I am going to address today: What is a useful and proper role for scientists in the public arena? How can we best discriminate where the boundary lies between expert knowledge, and values or political opinion, and how can we properly honor that line? What can we expect in the way of reception for our interventions and how can we increase their efficacy?

At the same time, I feel a bit sheepish about this task, because I’m sure some of my recommendations will sound obvious and trite to you, like Polonius’ “to thine own self be true”, although hopefully not that trite. In addition, while I intend to keep war stories to a minimum, I am after all a practitioner of public involvement rather than an academic expert on it, so my own experience is most of what I have to offer and I hope that suffices. Finally, I’m sure I have violated some of the recommendations I am about to put forth many times, many times. Involvement in the public arena is complicated.

This talk is structured as follows: first, I raise three questions which might be asked by any of us who are skeptical about scientists becoming involved in the public arena. I hope my answers will convince you that such involvement is sensible and to some degree inevitable. Second, noting that such involvement doesn’t mean all of us aspire to become a Carl Sagan or a Jim Hansen, I’ll propose a couple of broad principles and five potential options for involvement, each quite distinct, along with some advice on how to navigate each. Third, I’ll strike four cautionary notes, emphasizing the difficulties you will encounter if you chose to “go public”. By way of wrapping up, I’ll channel some advice from Steve himself.

But let me begin by providing some scholarly context for understanding Steve’s philosophy of how scientists could, should, and actually do engage with the public. There is a substantial literature on these questions, going back to CP Snow and probably earlier, and more recently including the views of Naomi Oreskes, Sheila Jasanoff, and Roger Pielke, Jr. The dilemma highlighted by CP Snow provides both a convenient jumping off point for this lecture and also a useful way to understand why Steve Schneider’s views were so central to our current concerns. So let me remind you of Snow’s argument in his 1959 lecture The Two Cultures, which if you hadn’t heard before, you probably did hear about during last year’s 50th anniversary of the event, which generated a lot of discussion in the pages of this community’s publications.

Why dredge up CP Snow’s argument again? Partly because his statement of the science-society communications problem was so clear, but also because, in a broad sense, the key challenges for the human endeavor on which he believed science should focus, remain unresolved, have grown even more complex, and were also at the center of Steve Schneider’s professional career. Furthermore, and in hindsight, Snow’s proposed solutions to the communications problem were not sufficient to overcome the complexity of the communications terrain, and how to navigate this terrain is after all the main subject of this talk.

In The Two Cultures, Snow, a physicist and novelist, issued a diatribe against Britain’s educated elite of the 1950s which foreshadows with remarkable prescience today’s perceived crisis in the public’s supposed lack of understanding of science, and the potential consequences of this shortfall, particularly in debates over the environment. Peel away the class critique of The Two Cultures and a deep fear over the incapacity of people to comprehend, and of government to tackle, the key issues of global resources and global equity, is revealed, broadly the same debate we are in the midst of now and which so engaged Steve. This pessimism sits side by side with optimism about technological possibilities for fixing these problems, if only science were heeded and mobilized.

Snow identified the key problem but misjudged the solution by failing to anticipate the complexity of the current world. Snow based his analysis on a juxtaposition that no longer is valid: the culture of physics providing one model of influential thought, and high-brow culture providing the other. Today, the physics model for scientific progress, which I’ll caricature as neat laws describing everything imaginable, deduced by geniuses and verified or falsified by experiments, seems relevant to a smaller and smaller set of public issues. Gradually, the model is being replaced by the more complex and uncertain way of thought characteristic of problems in geosciences, biology and environment. In these arenas, fact and value are sometimes harder to separate; and so it is not coincidental that these fields generate many of today’s political conflicts as well. Furthermore, culture among the influential is no longer particularly high-brow, so generalist versus expert is probably a better description of the current dichotomy.

The quandary is this: How can a society of generalists govern itself when most of the issues of the day are highly technical? Many solutions to this conundrum have been proposed by scientists: one is Snow’s idea of merging the scientific and popular cultures through improved education; another is a public-policy technocracy dominated by scientific elites, in some ways, the French model. Of course, these proposals cover only half the existing spectrum of opinion. Some people of faith might argue that science’s role in people’s education and public decisions ought to be entirely secondary.

Specifically, Snow argued that the scientific revolution was the last phase of the industrial revolution, and he saw the industrial revolution as a mixed bag. It brought general improvement but wide disparities. Snow’s argument anticipated the rise of China, the shifting of the economic balance among nations, and the importance of the global implications of seemingly local problems, particularly the population problem. He imagined science, integrated into education and politics, as the font of all solutions. And he saw scientists as wiser, more reliably ethical, and more inclined to an optimistic and activist view of human possibilities, than are others.

What Snow could not have appreciated is the limitations of science in the face of the complexity of the problems he had highlighted, and the resulting existence of a contested zone where values, judgment, and science fight it out for controlling influence over policy decisions. He also seemed blind to the limited ability of scientists to explain their own work so that their role in public education was in fact problematic to implement. Some scientists are fearful of treading into the contested terrain at all, while others do so but experience great difficulty in distinguishing its boundaries, and separating expert knowledge from value-laden, subjective judgments.

These fears and difficulties should not be surprising: many scientists loathe ambiguity as a permanent state because it is their job, our job to resolve it. Inability to do so is seen by us as either failure, or that we are dealing with substance that is beyond our expertise. Scientists like to deal with problems by draining them of values and ambiguity, and isolating “the facts”, and I think this accounts for the limitations of Snow’s vision. Politics and policy must inevitably reinsert the latter complexities. Scientists are in their hearts control freaks, but control is simply not possible to exert over such problems.

The human complexity of dealing with these issues, which Snow overlooked, was Steve Schneider’s favorite playground. In other words, Steve was a CP Snow for the post-modern era.

I’ll return to Steve’s views at the end of my talk, after outlining the conundrum that scientists face in considering involvement in the public arena: first, by addressing why participation in the public arena can’t be easily avoided; next by suggesting some ideas, based on my own experiences, which may help you formulate your own guidelines so that you can better calibrate your own participation.

Involvement in the public debate over public policy is a common and accepted role for scientists in many disciplines. In the sciences related to public health, it’s taken for granted that experts will talk loudly in public about the implications of their research for public policy, whether in regard to smoking, or diet, or HIV. There is also a remarkable track record of geoscientists taking a lead role in the public arena, and actually affecting public policy, in directions that many of us are grateful for.

Sherry Rowland’s public role on ozone depletion stands out, as do the contributions of Jim Hansen, Steve Schneider, and Bob Watson on climate. In other arenas, one can point to Hans Bethe and Henry Kendall at one end of the belief spectrum, or Edward Teller at the other. Some of these people mostly translated science for the wider public, others endorsed specific policy initiatives. I agree with the views of many of these scientists, and strongly disagree with others. One cannot prove that the world followed a better, or even a different course, due to their interventions. But I think the quality of public discourse and the information reaching policy makers was better for their interventions, taken as a whole.

Despite such examples, Jim Hansen has asserted that by and large, members of our community are reticent, hesitant to speak out about the implications of their research, and when they do, they take a cautious approach. By and large, he’s probably right, and I too would like to see my colleagues have more to say because I think they (you) have a lot to offer. But it’s not easy to do so in a satisfying way; the messages are easily misunderstood; our interventions are sometimes unhinged from our expertise in a way that is not helpful to the listener (after all, reticence is sometimes the right choice). Also, it’s not clear when, who or if, anyone is listening.

Finally, I assume that this audience holds a spectrum of views on the particulars of any scientific problem, which, like global warming, is characterized by large uncertainty, and I invite those in the audience who might have disagreements with me, to pay attention anyway, because you may well chose to engage in the public arena, and if so, you will face the same problems as I do.

Still, a scientist who doubts the necessity of such involvement might ask the following questions:

Question 1: Public involvement takes time. Can’t I stay in my office or lab while policy-makers and the public wrestle over what to do about the various technological problems we face?

Alas, I’m afraid this is increasingly difficult to do and if followed by the community as a whole, would be highly irresponsible. Science is not wholly owned by governments but it does draw a large fraction of its support from governments. I’ll return to the question of individual ethical obligation a bit later. For now, let me just say that this financial support means that science as an enterprise, if not individual scientists, owes something in return: the least we can do is be available to interpret our research findings, and if possible, explain their implications for society. But there is also a pragmatic reason to get involved: If we do not, we leave Congress, for example with the option of seeking explanations from those less competent to offer these up. Alternatively, we can be proactive about it and define the meaning and significance of our own work, rather than letting others do it for us.

Perhaps, if policy were linearly related to science, abstinence would be a plausible approach.

Question 2: Can’t we just make clean, scientific statements in English, and leave it at that?

Even if we could make clear and direct explanations of our work absent ambiguity yet honoring all our beloved caveats, interaction with the public is a dialogue, not a monologue. Even the “cleanest” statements demand elaboration once the inevitable follow-up questions begin to role in.

Let me provide an example in the form of a famous statement in the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment report, a statement renowned and highlighted in the report for its clarity and simplicity: “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal”.

What precisely about warming is unequivocal: that it has been occurring? That it will occur in the future? That the entire problem we call “global warming” is unequivocal in all aspects?

These are all questions that a reasonably intelligent person could raise when reading such a statement unless they also absorbed the minutiae of explanations and modifications which accompanied it in the report. In fact, the UN climate negotiators recently tripped on this very issue when they wrongly asserted that the statement meant that not only the fact that earth had warmed, but the attribution of this warming to human activity were both unequivocal.

We cannot simply drop our pearls of wisdom and expect others to deconstruct them. That much is our job.

Every time we emphasize or de-emphasize a point, assign likelihood to an outcome or refrain from doing so, we are exercising expert judgment about what is important and what is not. Similarly, every time we say an outcome “may” happen rather than it “may not”, or that it’s opposite may or may not occur, we are making such judgments. And those judgments are partly subjective because in many cases a different expert might justifiably have a different view and express it differently. Uncertainty goes hand-in-hand with subjective judgments, and with the necessity of making them.

For an entertaining example of this point, I urge all of you to see the movie “Fair Game”, and listen closely to the scene where former vice presidential aide Scooter Libby explains to a CIA analyst why words like “maybe” and “maybe not” matter in expressing expert judgment.

Question 3: OK, I’ll acknowledge that someone has to do the dirty work, but I’m not so good at communication. So I’d prefer to let everyone else take this on.

Wrong again. Ask some of our colleagues who never tried to be public figures or never said anything even mildly controversial but who nevertheless became collateral damage in so-called Climategate, the CRU email episode, just because they were recipients of mostly anodyne emails, sent by others.

To be blunt, science and scientists are now part of an unavoidable and contentious public discussion. This is no longer 1983 when the National Academy of Sciences could issue a monumental report on climate change and have it go virtually unnoticed. Climate and related issues are characterized by very high socioeconomic stakes: that’s the main reason why so much research money (relatively) is spent on them and why they generate so much public controversy. That’s life as it is and as it will be, for the foreseeable future. We as a community and as individuals can either try to frame that discussion, and be prepared for involvement, or let others who are less interested in scientific truths set the terms of the public discussion.

I am encouraged that institutions like AGU are eager to do more to defend and explain science, and are puzzling over and experimenting with approaches for doing so. But it’s not the institutions per se that carry the weight. In the end, it’s up to the individuals who constitute them, YOU.

Question 4: Am I obliged to get involved?

As I noted already, I am sure that the community as a whole has an obligation to society to be informative about the meaning and implications of its research findings, assuming society wants to hear such information. I am confident in this view because I understand that the public, through the taxes it pays, supports a large portion of our research, including for many, our salaries. Surely, there is some obligation in return that goes beyond merely working away in our offices or laboratories. I feel strongly that the obligation on the community as a whole is implicit.

But what about our individual obligations? Any involvement means lost research time. There is a credible argument that the world is better off with most of us just doing research and foregoing involvement. Still, we can’t all be free-riders or our community would have fallen down on its overall obligation. For me, it’s enough that people, through their leaders, through the media, and through individual requests, want the information. I am happy to provide it. And if they want my judgment about what to do about these problems, then I will provide that too, and try to be clear about which is which. In the end, each of you needs to decide for him/herself.

But there are two related and less contentious aspects of this obligation at which our community is failing miserably. First, we do little if anything to advise young scientists on the social and ethical context of the world into which they are about to enter: what are the implications of their research for other human beings, what constitutes honest representation of their research beyond the rules of professional review and publication, how might others use their research and how should they think about this transaction? NSF now requires instruction in research ethics, but that only scratches the surface. Are there any major research universities that require graduate students in our fields to take courses which would give them a complete framework for thinking about the obligations I have discussed, or the public context in which their scientific views will be received, interpreted, and utilized?

Our second failure is the inadequacy of the response to threats to individuals in our community. Our professional societies respond vigorously to threat to the community as a whole, as when the federal research budget is reduced. But they have had great difficulty figuring out how to address such attacks on individuals, or whether they have a role to play at all. But this is sort of the inverse of the free-rider problem: the individual lamb can be sliced off from the group and devoured and the group can ignore it but eventually, the whole heard is cut to shreds. AGU, NAS, AAAS, and the rest of our professional organizations need to learn how to differentiate reasonable complaints which call for a due process approach that can strengthen our enterprise, like the establishment of the committee to review IPCC by the Inter Academy Council, from unreasonable, unfair, and abusive attacks, which if met with silence, threaten to undermine the independence of science.

I hope I have convinced you that participation in the public arena is both desirable and to some degree unavoidable. If so, what are your options for involvement? And what are sensible guidelines for behavior in this arena? Let me provide some suggestions, based on my own experiences. The taste for, aptitude for, and utility of involvement in the public arena varies widely from scientist to scientist. So let’s consider a wide range of options:

Option 1: You can very publicly take sides, for instance in an election, based specifically on what you see as the policy implications of your research.

This is one end of the spectrum, and many of us individually have publicly and loudly supported candidates, including Presidential candidates. In a less-noticed way, many scientists sign onto collective campaign endorsements. It is argued by some that there is a price to pay for such activity, but the only one I’ve seen is that it is likely to rule you out for a political appointment if your candidate loses. But if getting such a job is not your objective, then why worry? But clearly, this end of the spectrum is not to everyone’s taste.

Concern also comes from an entirely different direction: that visible participation by scientists qua scientist in the political process dilutes the credibility and independence of science. I don’t know if we have proof on the latter point either way, but I merely note that scientists have long taken partisan positions as individuals, and I know of no evidence that it has done any damage to our collective reputation. An analog in a different arena is provided by Eisenhower’s running for President which some argued would be problematic for the image of the military. Was it? Closer to home, was former Senator and Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist’s emphasizing his credentials as a doctor problematic? In both cases, I think not. What was problematic for Frist was when he departed from his sound expert judgment as a doctor and began to make implausible pronouncements which he backed by his credentials, i.e., his TV diagnosis of Terry Schiavo.

My ground-rule here is clear: if you are going to use scientific arguments as a rationale for taking partisan positions, make sure you aren’t simple using your science as a cover for what are really political, not scientific judgments. In other words, make sure you feel comfortable in your scientific skin.

Option 2: You can take sides publicly on the policy implications of your research, including actively lobbying for particular policy proposals (by visiting representatives in Washington, writing letters to the editor, posting blogs, etc., or just answering questions from the media).

Again, there is no reason not to participate in this way. Scientists do it all the time. The least controversial example in our community occurs when scientists testify on Capitol Hill in favor of additional research funding. This is surely a political act based on scientific, as well as other, judgments and motivations. More controversial interventions, but also with a long pedigree, occur when scientists back particular initiatives related to their scientific findings, for example cap-and-trade, or carbon tax, or fuel-economy standards. In my lifetime, it’s been done by Edward Teller or Henry Kendall on nuclear arms control, or various biologists on stem cell research, or Paul Ehrlich on family planning, or Gene Likens on acid rain, or dozens of the people in this room on climate change. The public discourse is richer for these interventions, not poorer.

But I also argue for caution here. My ground-rule (and most decidedly Steve’s) is this: the further from your expertise you wander in making judgments about policy, the shakier ground you are on, and the more humility and caution is called for. It’s one thing to argue that within scientific uncertainty, warming of a given amount would cause a particular level of damage. But it’s a value judgment, not a scientific one, to argue that emissions reductions which could avoid the damage are necessary. And it is far outside the expertise of most people in this room to assert that one or another type of policy initiative is appropriate for getting there.

I do not argue that one should avoid such value-judgments, but like Steve, I think it’s important to be clear in your own mind, and to the public, which sort of judgment you are making. We are all entitled to our value judgments, our personal risk assessments, and they should be a key factor in public policy. But we are not entitled to make value judgments or political or policy judgments in areas where we are not experts, like politics or economics, and try to pass them off as following automatically from our scientific expertise.

I would like to be able to say that we should stop speaking as experts when we venture into terrain where we feel uncomfortable as experts. But for some reason, this approach has not worked very well. Some of our colleagues seem unaware of where their expertise ends, and they haven’t been willing to do the hard homework necessary to extend their expertise enough to justify their positions.