Note that my last post on additivity, and this one, are both examples where I'm thinking out loud. I'm still trying to sort out my views on these things.

I think Glenn's comment in the last post refers to the phenomenon of "leakage" or "slippage", which I have written and blogged about (see here). I don't have a problem with this jargon. Nor do I have a problem with any of the theoretical and empirical issues that dance around carbon offsets and similar policies that pay for conservation.

I guess my main concern is that the term "additive" may be too generic: it doesn't help to clarify where and how policies may be inefficient.

But, as Glenn points out, one of the big overarching issues here is that many conservation programs tend to put a price on environmental services in some contexts but not price them in other contexts. Or, almost equivalently, environmental gains are priced but environmental loses are not priced, or vice versa. It's very much like taxing pollution in one country and not taxing in another country. This is a big potential challenge with PES, especially for global environmental problems.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Monday, October 18, 2010

Do we really want payments for environmental services to be "additional"?

"Additionality" is big piece of jargon floating around in the academic/government literature on "payments for environmental services," or PES. Sadly, I think this word may be getting in the way of clear thinking about environmental policy.

The idea behind PES is basically the opposite of a pollution tax. The idea is to subsidize activities with positive externalities (like "environmental services") instead of or in addition to taxing negative externalities like pollution. So, we can pay people to plant forests to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and/or tax people who burn carbon-based fuels or cut down forests and thus emit CO2.

The idea behind additionality is that payments for new, carbon sequestering forests should be directed only at those who wouldn't have planted forests anyway, that are "additional." That sounds fair. But it also sounds impossible. After all, the whole idea behind pricing schemes, like PES, is to decentralize decision making to allow the most efficient way of achieving any given level of atmospheric carbon, or other environmental outcome. An efficient scheme just puts the right price on each unit of carbon, regardless of source.

The point is that we can't put a "price" on environmental services and enforce "additionality" at the same time. A ton of carbon is a ton of carbon. We cannot tell what it cost someone to provide it. So someone plants a tree in their back yard because they want the shade it provides. Suppose they also collect a payment for the carbon that tree sequesters. How can we know that they would have planted the tree anyway? Obviously, we can't. But that in no way affects the optimal policy.

Consider the converse: Should we only tax pollution that is non-additional? If so, how the heck would we do that?

The strange thing about additionality is that it's a concept that can only be implemented with perfect information. It would be much like a perfectly price-discriminating monopolist. If we want to go there, there's really no point to a pricing scheme at all, since the mechanism would effectively centralize all decision making by assigning individual-specific activities and compensation levels.

The idea behind PES is basically the opposite of a pollution tax. The idea is to subsidize activities with positive externalities (like "environmental services") instead of or in addition to taxing negative externalities like pollution. So, we can pay people to plant forests to sequester carbon from the atmosphere and/or tax people who burn carbon-based fuels or cut down forests and thus emit CO2.

The idea behind additionality is that payments for new, carbon sequestering forests should be directed only at those who wouldn't have planted forests anyway, that are "additional." That sounds fair. But it also sounds impossible. After all, the whole idea behind pricing schemes, like PES, is to decentralize decision making to allow the most efficient way of achieving any given level of atmospheric carbon, or other environmental outcome. An efficient scheme just puts the right price on each unit of carbon, regardless of source.

The point is that we can't put a "price" on environmental services and enforce "additionality" at the same time. A ton of carbon is a ton of carbon. We cannot tell what it cost someone to provide it. So someone plants a tree in their back yard because they want the shade it provides. Suppose they also collect a payment for the carbon that tree sequesters. How can we know that they would have planted the tree anyway? Obviously, we can't. But that in no way affects the optimal policy.

Consider the converse: Should we only tax pollution that is non-additional? If so, how the heck would we do that?

The strange thing about additionality is that it's a concept that can only be implemented with perfect information. It would be much like a perfectly price-discriminating monopolist. If we want to go there, there's really no point to a pricing scheme at all, since the mechanism would effectively centralize all decision making by assigning individual-specific activities and compensation levels.

Friday, October 15, 2010

Research subsidies with and without carbon prices

With climate change policy on the back burner, Ezra Klein, back in July, interviewed Michael Shellenberger about whether subsidies for research and development were a good substitute, or at least a politically viable substitute, for cap-and-trade or carbon taxes.

There's some interesting economic theory of the second best that sits beneath this question (see the bottom of the linked post).

Others are now getting on the bandwagon. The other day David Leonardt was channeling Michael Greentone, with a follow up channeling Nathaniel Kohane. Tyler Cowen also seems intrigued by the idea.

It's the kind of policy that might actually find some bipartisan support. Although big oil and coal probably wouldn't like this any better than cap and trade.

I'm sure a dozen or so theoretical environmental economists are busy working on just this topic.

There's some interesting economic theory of the second best that sits beneath this question (see the bottom of the linked post).

Others are now getting on the bandwagon. The other day David Leonardt was channeling Michael Greentone, with a follow up channeling Nathaniel Kohane. Tyler Cowen also seems intrigued by the idea.

It's the kind of policy that might actually find some bipartisan support. Although big oil and coal probably wouldn't like this any better than cap and trade.

I'm sure a dozen or so theoretical environmental economists are busy working on just this topic.

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

The corn-soybean belt is starting to walk North and West

Adaptation begins:

Associated Press:

But the article does give me an idea...

Associated Press:

The article is big on quotes from Bruce Babcock, who knows agriculture very, very well. But it's a little short on hard facts.DES MOINES, Iowa — Warmer and wetter weather in large swaths of the country have helped farmers grow corn, soybeans and other crops in some regions that only a few decades ago were too dry or cold, experts who are studying the change said.Bruce Babcock, an Iowa State University agriculture economist, said soybean production is expanding north and the cornbelt is expanding north and west because of earlier planting dates and later freezes in the fall.....

But the article does give me an idea...

First a supply shock, now a demand shock

Crop reports from the last few days reflected a downward shift in supply.

Today we have news about an outward shift in demand: a report that EPA is going to approve a 15% ethanol blend, up from 10%. That means demand for corn could rise from roughly one third of the U.S. crop to roughly half. Put another way, from about the 5% of the world's caloric base in grain/oil production (corn, soybeans, wheat and rice) to about 7.5%.

Yikes.

Oddly, prices didn't jump much with the news. I'd guess the market expected this ruling to be likely awhile ago.

Still, corn is back up to $5.77 a bushel. Wheat is above $7 and soybeans are trading at nearly $12. Rice is at $13.45, up from about $9.50 a few months ago. It's not 2008, but those are pretty high prices.

Today we have news about an outward shift in demand: a report that EPA is going to approve a 15% ethanol blend, up from 10%. That means demand for corn could rise from roughly one third of the U.S. crop to roughly half. Put another way, from about the 5% of the world's caloric base in grain/oil production (corn, soybeans, wheat and rice) to about 7.5%.

Yikes.

Oddly, prices didn't jump much with the news. I'd guess the market expected this ruling to be likely awhile ago.

Still, corn is back up to $5.77 a bushel. Wheat is above $7 and soybeans are trading at nearly $12. Rice is at $13.45, up from about $9.50 a few months ago. It's not 2008, but those are pretty high prices.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

The upsides of bad weather are...

(1) that grain farmers get rich;

and

(2) the topic of my personal interest gets major billing at the New York Times:

The big deal here is what happens to food prices in very poor countries, not the US or other relatively developed nations. Sadly, that's not mentioned in this article. Oh well.

The back story here is that: (1) for the last 15 years the weather has been strangely good in the Midwestern corn belt, which is, by far, the most important region in the world for basic grain production and (2) climate change forecasts indicate that strangely good weather will turn into catastrophically bad weather very soon.

I hope that doesn't happen. But if it does happen, and if we cannot adapt really, really fast, then consider: If a temporary downward production shock of 4.6%, buffered by ample inventories, causes grain prices to increase this much, what will a permanent downward production shock of 80% percent do?

Don't worry: your kids will eat just fine. The price of Big Mac will hardly change, even if corn prices triple or more. But it's not your kids I'm worried about.

And I'm not saying this will happen. But I do think the risk is very real.

and

(2) the topic of my personal interest gets major billing at the New York Times:

Rising Corn Prices Bring Fears of an Upswing in Food Costs:

First it was heat and drought in Russia. Then it was heat and too much rain in parts of the American Corn Belt. Extreme weather this year has sent grain prices soaring, jolting commodities markets and setting off fears of tight supplies that could eventually hit consumers’ wallets.

In the latest market lurch, corn prices dropped in early October, then soared anew, in response to changing assessments by the federal government of grain supplies and coming harvests.

The sudden movements in commodities markets are expected to have little immediate effect on the prices of corn flakes and bread in the grocery store, although American consumers are likely to see some modest price increases for meat, poultry and dairy products.

But experts warn that the impact could be much greater if next year’s harvest disappoints and if 2011 grain harvests in the Southern Hemisphere also fall short of the current robust expectations.

“We can live with high commodity prices for a period without seeing much impact at the retail level, but if that persists for several months or a couple of years, then it eventually has to get passed on” to consumers, said Darrel Good, an emeritus professor of agricultural economics at the University of Illinois.

....Uhm, with all due respect to Dr Good (whoes work I generally admire) this is kind of silly, as the article (much later) points out:

That is because the cost of basic grains makes up only a small fraction of the total cost of most manufactured foods that contain them, such as breakfast cereals or bread. A large part of the cost of those items comes from transportation, processing and marketing.Perhaps that is a quote taken out of context by a reporter trying to make a splash up front. But since it is The Times, after all, they have to get honest further down in the column, where fewer readers venture (I'm feeling Brad Delong's theme here: Why oh why can't we have a better press corps?)

The big deal here is what happens to food prices in very poor countries, not the US or other relatively developed nations. Sadly, that's not mentioned in this article. Oh well.

The back story here is that: (1) for the last 15 years the weather has been strangely good in the Midwestern corn belt, which is, by far, the most important region in the world for basic grain production and (2) climate change forecasts indicate that strangely good weather will turn into catastrophically bad weather very soon.

I hope that doesn't happen. But if it does happen, and if we cannot adapt really, really fast, then consider: If a temporary downward production shock of 4.6%, buffered by ample inventories, causes grain prices to increase this much, what will a permanent downward production shock of 80% percent do?

Don't worry: your kids will eat just fine. The price of Big Mac will hardly change, even if corn prices triple or more. But it's not your kids I'm worried about.

And I'm not saying this will happen. But I do think the risk is very real.

Hans Rosling on child mortality statistics

A new TED talk:

I wonder: What's the link between food prices and child mortality? I know Egypt worked hard to keep food very cheap, and that must have helped, as has the steady global decline in commodity prices.

I wonder, and also worry, if cheap food is something we've taken for granted.

I wonder: What's the link between food prices and child mortality? I know Egypt worked hard to keep food very cheap, and that must have helped, as has the steady global decline in commodity prices.

I wonder, and also worry, if cheap food is something we've taken for granted.

Monday, October 11, 2010

Ezra Klein on external economies, superstars, the large rewards of small differences, and public investment

Ezra Klein doesn't have a PhD in economics, but his economic thinking transcends that of many PhDs I know. And he writes much better. I blame it all on the fact that he grew up in a much richer technological environment than I did.

Ezra Klein :

Ezra Klein :

"The idea of the lone genius who has the eureka moment where they suddenly get a great idea that changes the world is not just the exception, but almost nonexistent," says Steven Johnson, author of "Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation." That's because innovation, whatever the Facebook movie told you, isn't really about individuals. And in making it about individuals, we misunderstand, and thus impede, innovation.

I was not born ... superior to my grandparents. But I would have been much likelier to invent Facebook than they were. The natural capabilities of human beings don't change much ... their environments do, and ... technology .... Better sanitation .... Transportation .. communication ... the Internet makes the coding of social networks possible.

.. advances happen... to many people simultaneously... ... In 2003, we were all social network geniuses, at least compared with everyone in 1993.

Consider CU Community, a Facebook competitor started at Columbia University. Adam Goldberg, its creator, programmed his social network... in 2003. It was more advanced than Facebook, ... though it did lack the elegant minimalism of Zuckerberg's design...

Today, Zuckerberg is many times as rich as Goldberg. ...attributed partly to the clean interface .. Harvard name and ... luck. ..the difference between Mark Zuckerberg and Adam Goldberg was very small..... It was the commons supporting them both that really mattered. But the focus on individuals leads us to overinvest in the rewards for individual innovation and underinvest in the intellectual commons that make those innovations possible. We're investing, in other words, in the difference between Zuckerberg and Goldberg rather than the advances that brought them into competition.

Consider the current debates in Congress. Republicans are fighting to add $700 billion to the deficit to extend the Bush tax cuts for income above $250,000. It is hard to imagine the innovations that happen at a 35 percent tax rate for your two-hundred-thousand-and-fifty-first dollar, but not at 39 percent. We're also helping creators and their heirs hold legal monopolies on innovations for much longer, extending individual copyrights to the life of the author plus 70 years, for instance. Would we lose so many great ideas if the monopoly lasted only until 15 years after the inventor's death?

At the same time... California is gutting its flagship system of universities. Salaries are dropping, and research money is drying up. ... 43 states have cut funding for higher education, while 33 others -- plus the District of Columbia -- have hacked away at K-12. And Congress seems to have given up on the energy and climate bill that could've kick-started our green energy industry -- even as China has committed almost a trillion dollars...

And let's not kid ourselves into thinking that public investments don't matter. Direct public investment was crucial for developing a national railroad system, planes and semiconductors. It was behind the Internet and the Global Positioning System. It was behind the educated populace that developed those innovations.

Nor should we be overly sanguine about the private sector's interest in innovation. The average company spends 2.6 percent of its budget on research and development, and a National Science Foundation survey found that only 9 percent of companies reported a product innovation between 2006 and 2008. "You can't be an innovative economy if only 9 percent of your companies are innovating," economist Michael Mandel wrote.

People ... want to make money...., to "make something cool." And they should be richly rewarded for their successes.

But there really isn't a replacement for public investment, and good rules. You need a good education system. You need intellectual-property rules that ensure space for new ideas and uses. ....we want to spend our limited dollars on ... the reality of innovation behind Facebook. [my emphasis]

Another big revision in USDA's crop forecast

It wasn't just wheat that was way off earlier forecasts, but corn and soybeans too.

Bloomberg:

The headline over at USDA was kind of interesting:

For comparison, here is the press release from August:

For a little historical perspective, here are September, October, and November forecasts for corn yields since 1995:

Typically there is very little if any revision between the November forecast and the final yield.

The first thing to note is that usually the September forecasts are very good. This year and 2004 are the exceptions. And, usually when forecasts are off by anything larger than a trivial amount, it's an upward correction, not a downward correction.

Another interesting thing to note is that the October forecast almost always sits between the September and November forecasts. I think last year (2009) is the only exception. That suggests the crop will actually turn out worse than the current forecast.

A grad student is busy updating our fine scale weather data now. I'll look forward to looking at the final yield and weather data to see if anything interesting emerges.

Bloomberg:

-- Corn futures are called to open 40 cents to 45 cents a bushel higher on the Chicago Board of Trade after the government said U.S. production will be less than forecast a month ago, said Greg Grow, the director of agribusiness for Archer Financial Services Inc. in Chicago.It's a bit early to know for sure, but I'm guessing that late-season heat wave did more damage than people thought.

-- Soybean futures may open 40 cents to 50 cents a bushel higher in Chicago after the U.S. government reduced its crop forecast and dry weather threatens yields in South America, Grow said. Soybean-meal futures may open $15 to $17 higher per 2,000 pounds, and soybean oil is expected to open up 0.75 cent to 0.85 cent a pound.

-- Wheat futures may open 6 cents to 8 cents a bushel higher on the CBOT, the Kansas City Board of Trade and the Minneapolis Grain Exchange as surging corn prices increase demand for wheat in feed rations and dry weather may curtail acreage in the southern Great Plains in the U.S., Grow said.

The headline over at USDA was kind of interesting:

This is strange given the real news was that both soybean and corn forecasts were way down from their September numbers. Another strange thing is how they emphasize "a warm growing season" in the first line. Without a little bit of contextual knowledge one may draw an impression that the warm growing season was what drove production to its "record-high year."USDA Forecasts Record-High Soybean Crop

WASHINGTON, Oct. 8, 2010 – On the heels of a warm growing season, U.S. soybean production is forecast at a record-high level, according to the Crop Production report, released today by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

Soybean production remains on target for a record-high year and is forecast at 3.41 billion bushels, up 1 percent from the previous record, set in 2009. Soybean yield is expected to average 44.4 bushels per acre, up 0.4 bushels from 2009. If realized this will be the highest yield on record. Soybean growers are expected to harvest a record-high 76.8 million acres, down 1 percent from the September estimate, but up 0.6 percent from last year’s acreage.

Corn production is forecast at 12.7 billion bushels, down 3.4 percent from last year’s record. Based on Oct. 1 conditions, corn yield is expected to average 155.8 bushels per acre, down 8.9 bushels from 2009. If realized, this will be the third highest yield on record. Growers are expected to harvest 81.3 million acres, up 0.3 percent from the September forecast.

For comparison, here is the press release from August:

WASHINGTON, Aug. 12, 2010 – U.S. farmers are on pace to produce the largest corn and soybean crops in history, according to the Crop Production report released today by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).There was no official press release in September (post heat wave) when the corn yield was revised down just a little bit to 162.5.

Corn production is forecast at 13.4 billion bushels and soybean production at 3.43 billion bushels, both up 2 percent from the previous records set in 2009. Based on conditions as of August 1, corn yields are expected to average a record-high 165 bushels per acre, up 0.3 bushel from last year’s previous record. Soybean yields are expected to equal last year’s record of 44 bushels per acre.

For a little historical perspective, here are September, October, and November forecasts for corn yields since 1995:

Typically there is very little if any revision between the November forecast and the final yield.

The first thing to note is that usually the September forecasts are very good. This year and 2004 are the exceptions. And, usually when forecasts are off by anything larger than a trivial amount, it's an upward correction, not a downward correction.

Another interesting thing to note is that the October forecast almost always sits between the September and November forecasts. I think last year (2009) is the only exception. That suggests the crop will actually turn out worse than the current forecast.

A grad student is busy updating our fine scale weather data now. I'll look forward to looking at the final yield and weather data to see if anything interesting emerges.

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Two small points for the supply siders in the macro wars

I've been blogging less on the macro wars. It is something I follow but really cannot comment on with much authority. I am happy to see that monetary verses fiscal policy discussions have become somewhat more pointed and more clear (see here, here, here, here, here, here, for example). This was something I had expected to see a lot more of a lot earlier. But everything takes longer than you expect, no?

I do agree with the Delong-Krugman front that the evidence overwhelmingly supports Keynesian and New Keynesian views, even if these views can be harder to publish in the academic journals. Indeed, I think on the evidence front, real business cycle models have looked bad for a very long time, well before the recent crisis and recession. I recall reading Robert Lucas admitting as much, also long before the recent crisis. It certainly is sad that academic fashion constrains research effort on questions that really matter for policy. That shouldn't happen.

Clearly, political and ideological leanings affect the intellectual debate, with Republican-leaning types mostly ascribing to the modern macro (aka "supply side") approach and Democrat-leaning types ascribing to the older Keynesian (aka "demand side") approach to explaining business cycles (there are notable exceptions, including Rogoff and Mankiw, who are Keynesian but decidedly conservative politically.)

I'm sympathetic to the demand-side view. Given this, it seems important to bend over backwards to understand where the other side may be coming from. So, what substance is there, if any, to the supply-side view?

I would award two key points to supply side crowd.

(1) Sometimes supply-side factors do matter for business cycles. The best examples are the oil price shocks of the 70s and early 80s. Those came from real supply shocks or reasonable fears of real supply shocks, which fundamentally reduced aggregate output and increased inflation. It was a rare example of stagflation and counter-example to the Phillips-curve like behavior wherein unemployment and an inflation are inversely related. The negative effects of oil price shocks on the macroeconomy were real and very much supply-side pheonomena.

(2) In Keynesian models, very little is said about the cause of business cycles. It's a product of animal spirits, fear, excess demand for money or safe assets, etc. Combine one or more of these with (very real and easy-to-explain) sticky prices and you have nasty demand-driven business cycles. But how do we go about modeling the driver of the shock in the first place? Keynesian models don't have a good answer to that question. When you read vague notions of "confidence," this is what it's all about. If everyone loses confidence, we have a downward shift in demand, followed by recession. In a Keynesian world, fear itself is the seemingly the consummate cause of our malaise. Blame Steven Colbert.

On the one hand, some might argue that a good answer to the question in 2 is very much beside the point. We have high unemployment and near-deflationary price expectations, and the Keynesian model gives clear policy prescriptions, like fiscal stimulus, quantitative easing and inflation targeting. On the other hand, it seems hard to put animal spirits into a model, so the Keynesian story seems incomplete, and this is enough for the supply siders to completely ignore it. So, without a clear formal link to the drivers of confidence, it will be hard to communicate with true supply-side believers, who also happen to control the editorial boards of the macro journals.

What to do?

It seems to me there is plenty of room for middle ground here. It seems to me that a formal model of "confidence" should not be so difficult to construct. All we need is to have expectations about the future be critically sensitive to certain kinds of information. Real productivity shocks, the traditional source of information in RBC models, clearly are not the kinds of information fundamental to big recessions. The non-bailout of Lehman Brothers did not cause a "great forgetting" about how to produce things. What it did was change the market's expectations about whether a lot of contracts would be fulfilled. It changed beliefs about who really owned what, or who would really own what. Institutionalists might say that property rights suddenly became more ambiguous. Thus, the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers made the world suddenly appear a lot riskier. Fear exploded, for not altogether irrational reasons. The rest follows from sticky prices.

So, is it really so hard to see how to model the effect of an event, like the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers, could lead to such a change in expectations? I think not. If I blur my eyes just a little it seems to me such a model could be constructed from a game of incomplete information. Individuals do not know the precise payoffs of the game they are playing and an innocuous, non-fundamental event rationally changes beliefs about which game (which payoffs) are really on the table. We have this kind of machinery in economics already. If such a model is then combined with any reasonable model with nominal price rigidities (of which there are many), we will have New Keynesian model that reconciles (2).

Does such a model exist? If it does, I'm not aware of it. But me being unaware of it wouldn't be so surprising either.

I do agree with the Delong-Krugman front that the evidence overwhelmingly supports Keynesian and New Keynesian views, even if these views can be harder to publish in the academic journals. Indeed, I think on the evidence front, real business cycle models have looked bad for a very long time, well before the recent crisis and recession. I recall reading Robert Lucas admitting as much, also long before the recent crisis. It certainly is sad that academic fashion constrains research effort on questions that really matter for policy. That shouldn't happen.

Clearly, political and ideological leanings affect the intellectual debate, with Republican-leaning types mostly ascribing to the modern macro (aka "supply side") approach and Democrat-leaning types ascribing to the older Keynesian (aka "demand side") approach to explaining business cycles (there are notable exceptions, including Rogoff and Mankiw, who are Keynesian but decidedly conservative politically.)

I'm sympathetic to the demand-side view. Given this, it seems important to bend over backwards to understand where the other side may be coming from. So, what substance is there, if any, to the supply-side view?

I would award two key points to supply side crowd.

(1) Sometimes supply-side factors do matter for business cycles. The best examples are the oil price shocks of the 70s and early 80s. Those came from real supply shocks or reasonable fears of real supply shocks, which fundamentally reduced aggregate output and increased inflation. It was a rare example of stagflation and counter-example to the Phillips-curve like behavior wherein unemployment and an inflation are inversely related. The negative effects of oil price shocks on the macroeconomy were real and very much supply-side pheonomena.

(2) In Keynesian models, very little is said about the cause of business cycles. It's a product of animal spirits, fear, excess demand for money or safe assets, etc. Combine one or more of these with (very real and easy-to-explain) sticky prices and you have nasty demand-driven business cycles. But how do we go about modeling the driver of the shock in the first place? Keynesian models don't have a good answer to that question. When you read vague notions of "confidence," this is what it's all about. If everyone loses confidence, we have a downward shift in demand, followed by recession. In a Keynesian world, fear itself is the seemingly the consummate cause of our malaise. Blame Steven Colbert.

On the one hand, some might argue that a good answer to the question in 2 is very much beside the point. We have high unemployment and near-deflationary price expectations, and the Keynesian model gives clear policy prescriptions, like fiscal stimulus, quantitative easing and inflation targeting. On the other hand, it seems hard to put animal spirits into a model, so the Keynesian story seems incomplete, and this is enough for the supply siders to completely ignore it. So, without a clear formal link to the drivers of confidence, it will be hard to communicate with true supply-side believers, who also happen to control the editorial boards of the macro journals.

What to do?

It seems to me there is plenty of room for middle ground here. It seems to me that a formal model of "confidence" should not be so difficult to construct. All we need is to have expectations about the future be critically sensitive to certain kinds of information. Real productivity shocks, the traditional source of information in RBC models, clearly are not the kinds of information fundamental to big recessions. The non-bailout of Lehman Brothers did not cause a "great forgetting" about how to produce things. What it did was change the market's expectations about whether a lot of contracts would be fulfilled. It changed beliefs about who really owned what, or who would really own what. Institutionalists might say that property rights suddenly became more ambiguous. Thus, the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers made the world suddenly appear a lot riskier. Fear exploded, for not altogether irrational reasons. The rest follows from sticky prices.

So, is it really so hard to see how to model the effect of an event, like the non-bailout of Lehman Brothers, could lead to such a change in expectations? I think not. If I blur my eyes just a little it seems to me such a model could be constructed from a game of incomplete information. Individuals do not know the precise payoffs of the game they are playing and an innocuous, non-fundamental event rationally changes beliefs about which game (which payoffs) are really on the table. We have this kind of machinery in economics already. If such a model is then combined with any reasonable model with nominal price rigidities (of which there are many), we will have New Keynesian model that reconciles (2).

Does such a model exist? If it does, I'm not aware of it. But me being unaware of it wouldn't be so surprising either.

Friday, October 8, 2010

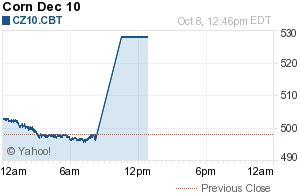

Big inventory adjustment, big price spike

It is odd to have such a large inventory adjustment this late in the season. Usually, most of the news about the size of crop is out by September.

What happened?

For economics geeks, this does provide a fairly powerful natural experiment for measuring the fundamental relationship between inventories and prices, since this large short-run move in prices likely has very little to do with a shift in demand.

What happened?

For economics geeks, this does provide a fairly powerful natural experiment for measuring the fundamental relationship between inventories and prices, since this large short-run move in prices likely has very little to do with a shift in demand.

The social costs and benefits of electric cars

There is a nice Room for Debate series at the New York Times on electric cars. See here.

I like Chris Knittel's position best:

One argument in favor of subsidizing electric cars concerns the learning that will need to place to organize around new kinds of refueling stations and routines. It seems to me this kind of thing will take experience, not just R&D.

Second, is economies of scale. This is probably limited, but I imagine that if batteries were built on a larger scale then costs may decline somewhat. This issue is important only insofar as it combines with refueling/network issue.

Despite these two points, I think Knittel is probably right here: the subsidies would almost surely be better spent on R&D. If they can figure out a better, more inexpensive battery, all kinds of great things will happen, and that extends well beyond electric cars.

I like Chris Knittel's position best:

The all-electric Nissan Leaf is an exciting new product in the automobile market...A couple thoughts not mentioned by Knittel:

The benefits of all-electric vehicles from an environmental perspective are clear. In terms of climate change, electric motors are more efficient than internal combustion engines requiring less energy to travel the same distance. If the electricity powering the vehicles comes from low greenhouse gas-emitting sources, the transportation sector can significantly reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. In terms of local pollutants, electric vehicles move the location of these emissions from city streets to rural areas where fewer people are affected.

But there are two factors that may keep electric vehicles from being the technology of the future. First, ...[g]one will be gas stations, replaced by either 440 volt quick charge stations that will still require at least 30 minutes to charge the batteries, or battery exchanges ....

Will consumers be willing to only charge at night, or wait 30 minutes to charge during the day? The frustrated faces I see when consumers have to wait for one car to finish refueling at gas stations suggests not. Adding to these frustrations is the fact that the range of the Leaf is roughly 100 miles...

Second, batteries are expensive. They are so expensive that for most uses, even accounting for the added cleanliness of the Leaf, the full lifetime cost of the Nissan Leaf will be greater than a comparable gasoline-powered sedan.

Heavy state and federal subsidies may make the Leaf privately economic for some of us. The key question, however, is whether ... that money be better spent elsewhere? The answer appears to be yes.

The main economic argument for subsidizing .... costs in the future fall as a result of experience in building the product ... Unfortunately, the evidence on such “learning” is weak. .... It is true that costs of hi-tech products fall over time. But for many products, however, this is due to technological progress, not learning. ...

My own work suggests that ...[h]ad we kept weight and horsepower constant, fuel economy would have increased by 50 percent from 1980 to 2006. In practice, it increased by 12 percent, while weight increased by 30 percent and horsepower doubled.

All of this suggests that the money going to subsidizing the Leaf would be better spent subsidizing research and development. We might even go further and say the money should be used to subsidize battery R&D. In the short term (and the long term), if we want to reduce emissions from the transportation sector, we need to offer incentives for people to drive less and purchase more efficient vehicles. The most cost-effective way to do this is through a carbon tax or a cap and trade system. These approaches have the added benefit that they generate revenue that can be used to either lower income taxes or increase R&D subsidies.

One argument in favor of subsidizing electric cars concerns the learning that will need to place to organize around new kinds of refueling stations and routines. It seems to me this kind of thing will take experience, not just R&D.

Second, is economies of scale. This is probably limited, but I imagine that if batteries were built on a larger scale then costs may decline somewhat. This issue is important only insofar as it combines with refueling/network issue.

Despite these two points, I think Knittel is probably right here: the subsidies would almost surely be better spent on R&D. If they can figure out a better, more inexpensive battery, all kinds of great things will happen, and that extends well beyond electric cars.

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Transit economics

Paul Krugman was hoping his commute to and from New York would be improved by the development of a new tunnel. Much to his chagrin, the project was scuttled by the New Jersey governor.

Looking on the bright side, it does bring some attention to a big and important area of environmental economics. A good place for analysis of these issues is Resources for the Future. An example is this report by Ian Parry and Kenneth Small, abstract below:

How would Tea Partiers feel about selling all the roads to private businesses that could then charge any price they wished to people who drove on them? That would have sounded absurd a decade or two ago, and maybe it still does. But with inexpensive GPS and cheap, fast computers, I don't see why this isn't now feasible.

Somehow me thinks people, even self-described conservatives, wouldn't like it.

Update: Krugman went further and turned this into his headline column, with a broader theme about infrastructure investment.

Tunnel Of Idiocy

Many reports that Chris Christie is about to scuttle the second rail tunnel under the Hudson. If so, it’s arguably the worst policy decision ever made by the government of New Jersey — and that’s saying a lot.

The story seems to be that Christie wants to divert the funds to road and bridge repair; but in so doing he would (a) lose huge matching funds from the Port Authority and the Feds (b) delay indefinitely a project NJ needs desperately ASAP. He could avoid these consequences by raising gasoline taxes. But no, taxes must never be raised, no matter what the tradeoffs.

And it’s a social bad too: now is very much the time when we should be ramping up infrastructure spending, not cutting it.In a follow up post he explains the essence of transit economics:

The usual suspects on the comment board are, inevitably, arguing that rail transit should pay for itself. The obvious response is that road transit doesn’t; why should only public transit have to self-finance, when private vehicles generally drive on free roads built and maintained out of taxes?

But in a way that misses the larger point: urban transportation is an area in which we know that market prices bear very little relationship to true social costs. Even if you ignore environmental impacts and the national security implications of oil imports, the fact is that driving in an urban area, especially in rush hour, imposes huge congestion externalities on other people. And I mean huge: Felix Salmon had a nice piece last year putting the external cost you impose on other people by driving into lower Manhattan at $160 a day...

Now, Econ 101 says that the first-best answer to these externalities is to make people pay these social costs; if we did, New Jersey Transit could charge much higher fares! But since that isn’t going to happen — at best, we may someday get a modest congestion charge — we’re into second-best territory.

And rail transit takes people off the roads, thereby yielding a large benefit that doesn’t show in NJT’s books....I think Krugman has it right here. But I guess Christie wasn't much persuaded by him. Oh well.

Looking on the bright side, it does bring some attention to a big and important area of environmental economics. A good place for analysis of these issues is Resources for the Future. An example is this report by Ian Parry and Kenneth Small, abstract below:

This paper derives intuitive and empirically useful formulas for the optimal pricing of passenger transit and for the welfare effects of adjusting current fare subsidies, for peak and off-peak urban rail and bus systems. The formulas are implemented based on a detailed estimation of parameter values for the metropolitan areas of Washington (D.C.), Los Angeles, and London. Our analysis accounts for congestion, pollution, and accident externalities from automobiles and from transit vehicles; scale economies in transit supply; costs of accessing and waiting for transit service as well as service crowding costs; and agency adjustment of transit frequency, vehicle size, and route network to induced changes in demand for passenger miles.

The results support the efficiency case for the large fare subsidies currently applied across mode, period, and city. In almost all cases, fare subsidies of 50 percent or more of operating costs are welfare improving at the margin, and this finding is robust to alternative assumptions and parameters.I should note that RFF is a well-respected, non-partisan institution that is not especially liberal. And I gather that Ian Parry actually leans pretty conservative.

How would Tea Partiers feel about selling all the roads to private businesses that could then charge any price they wished to people who drove on them? That would have sounded absurd a decade or two ago, and maybe it still does. But with inexpensive GPS and cheap, fast computers, I don't see why this isn't now feasible.

Somehow me thinks people, even self-described conservatives, wouldn't like it.

Update: Krugman went further and turned this into his headline column, with a broader theme about infrastructure investment.

Tuesday, October 5, 2010

You don't need to be a Keynesian to see a lot of potential government expenditures for which the benefits would far outweight the costs

Imagine you're in debt well past your eyebrows and then lose your job. The only thing you can do to pay down your debt is collect aluminum cans and recyclable plastic bottles from trash bins and redeem them for pennies. You'll never repay your debt at this rate, but you dutifully send your pennies to your lenders and live off food stamps.

Now suppose there's another alternative. A high paying job across town is available for you, but to accept this job requires that you buy a car for the commute, a car that you can only buy by going deeper into debt. Lenders trust you deeply and are not only willing to lend to you but are willing to lend to you cheaply, at a near-zero rate of interest. And the job pays well enough to pay off both new car loan debt and contribute significantly more to paying down your current debt.

Should you take out the loan, buy the car and take the job across town?

Obviously, yes. But some would claim that you're already deep into debt, so you should stop digging.

This, in fact, is the world we live in:

Ezra Klein

Furthermore, this kind of spending would likely spur growth, including tax revenue growth, in both the short run [if you do have a Keynesian bone], through positive feedback and employment of idle capacity, and in the long run with greater productivity, all of which could ultimately help shrink the deficit.

This isn't complicated. So why are so few pointing out the obvious?

Now suppose there's another alternative. A high paying job across town is available for you, but to accept this job requires that you buy a car for the commute, a car that you can only buy by going deeper into debt. Lenders trust you deeply and are not only willing to lend to you but are willing to lend to you cheaply, at a near-zero rate of interest. And the job pays well enough to pay off both new car loan debt and contribute significantly more to paying down your current debt.

Should you take out the loan, buy the car and take the job across town?

Obviously, yes. But some would claim that you're already deep into debt, so you should stop digging.

This, in fact, is the world we live in:

Ezra Klein

People say that the government should be run more like a business. So imagine you are CEO of the government. Your bridges are crumbling. Your schools are falling apart. Your air traffic control system doesn't even use GPS. The Society of Civil Engineers gave your infrastructure a D grade and estimated that you need to make more than $2 trillion in repairs and upgrades.

Sorry, chief. No one said being CEO was easy.

But there's good news, too. Because of the recession, construction materials are cheap. So, too, is the labor. And your borrowing costs? They've never been lower. That means a dollar of investment today will go much further than it would have five years ago -- or is likely to go five years from now. So what do you do?

If you're thinking like a CEO, the answer is easy: You invest. You get it done. Happily, that's what the administration is proposing to do. But its plan is too modest. The $50 billion bump in infrastructure spending it has proposed is only for surface transportation. The infrastructure bank envisioned in the proposal is also likely to be limited to transportation. And as for our water systems, our schools, our levees? This is not a time for half-measures. It's a rare opportunity to do what we need to do and to save money doing it.

...Ezra certainly has a point. But where his emphasis is on infrastructure, even more I lament disinvestiment in human capital, which is the larger public good. Private returns to education are large and have increased over time. The social returns to education are even larger. And government borrowing costs are very low. Economically speaking, it seems a bad time for furlough Fridays in primary schools, where educational returns are the greatest.

Furthermore, this kind of spending would likely spur growth, including tax revenue growth, in both the short run [if you do have a Keynesian bone], through positive feedback and employment of idle capacity, and in the long run with greater productivity, all of which could ultimately help shrink the deficit.

This isn't complicated. So why are so few pointing out the obvious?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...