On an earlier post someone asked: Why, with commodity prices so high, hasn't the price of meat gone up?

I have two basic answers.

1) Meat, especially if we're talking about meat you buy in the grocery store, is ultimately derived from commodities like corn and soybeans, which are the primary source of animal feed. But there are a lot of steps involved with raising the animals and processing and marketing them. So the price of meat, like most everything else we buy, is mostly made up of labor costs along that chain, not the price of the raw material inputs. This is why we here in rich countries hardly perceive the effects of rising commodity prices (except maybe for gas), but folks in places like Egypt who are living on $2 day can feel the higher price of wheat in a way we just cannot comprehend.

2) There can be a long lag between the time when corn and soybean prices rise and meat prices rise. In fact, in the short run, meat prices can fall because meat producers, squeezed by higher input costs, are forced to liquidate their inventories. That is, take their breeding stock to the slaughterhouse. Thus, in the short run prices may fall as the market is flooded. But in the longer run, with a smaller breeding stock, the supply of meat shifts in, ultimately driving up meat prices. The opposite can happen when commodity prices fall, since meat producers must reduce supply in the short run in order to increase breeding stock and supply in the long run. The key issue here is that animals are both a consumption good and capital, which can give rise to cattle cycles.

Update: I don't follow meat markets as much, but I just took a gander and noticed that while live animal prices haven't gone up as much as other commodities, they are up. But frozen pork bellies are up a lot. What's the difference? Frozen pork bellies, like basic grains, are storable, which allows anticipated higher future prices to be realized right here and now.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Commodity price rises are fundamental, not monetary

I liked Paul Krugman's column today.

One thing he did not exactly say but I wish he had: Commodity price rises have little to do with monetary and currency policies in the US and around the world. To the extent that they are connected, they are connected through the market's attempt to correct long-held imbalances, particularly China's undervalued currency. China's inflation is the market fighting that undervaluation, and that inflation is helping to spur demand for commodities. But what's important to note is that the underlying demand is fundamental: it would have been there long ago except for China's past suppression of it through currency policy. By the same token, China's inflation is helping to balance our trade deficit.

We'd be wise to think about possible collateral damage of higher commodity prices, since I suspect high prices could be here to stay. But this really should have no bearing on monetary policy.

One thing he did not exactly say but I wish he had: Commodity price rises have little to do with monetary and currency policies in the US and around the world. To the extent that they are connected, they are connected through the market's attempt to correct long-held imbalances, particularly China's undervalued currency. China's inflation is the market fighting that undervaluation, and that inflation is helping to spur demand for commodities. But what's important to note is that the underlying demand is fundamental: it would have been there long ago except for China's past suppression of it through currency policy. By the same token, China's inflation is helping to balance our trade deficit.

We'd be wise to think about possible collateral damage of higher commodity prices, since I suspect high prices could be here to stay. But this really should have no bearing on monetary policy.

Saturday, January 29, 2011

Commodity prices and speculation, again

The other week I got a list of questions from a journalist at China's Life Week, which is presumably the country's biggest news magazine.

The journalist asked:

1. I think prices are rising mainly in response to increased growth and demand in the Southern Hemisphere and Asia, but particularly from China.

2. Speculation is an important part of commodity prices, but as far as I can tell, only in good ways. For example, if the market expects demand to rise in the future, prices may go up today, since some of today's production will be placed in inventories in anticipation of higher future demand. Without speculation, we wouldn't have markets trying to maneuver production from times when it is less valued to times when it will be more valued.

Note that speculation does not necessarily imply a speculative bubble. I do not think there is a speculative bubble in commodities, nor do I think has been one in recent history. I agree with the likes of Paul Krugman who has pointed out several times, that for there to be a speculative bubble in commodity prices, there needs to be a general buildup in inventories. We have not seen such a buildup in inventories. It's been quite the opposite: prices have gone up in response to declines in inventories. This is what happened in 2008 as well.

3. I don't think the money coming out of index funds has anything to do with commodity prices.

4 & 5 I think biofuel demand, artificially stimulated by government subsidies, was a big factor in the 2008 rise and one factor keeping prices high today. In my work with Wolfram Schlenker (currently under revision for the American Economic Review) we find the *long run* effect of the biofuel demand on the world's major staple commodity prices is on the order of 20-30 percent. But in the short run, the spike could have been larger. It also had the effect of drawing down inventories which made market prices far more susceptible to temporary weather or other kinds of shocks.

6. I think U.S. biofuel policy is misguided, mainly for the reasons outlined in 4&5--these costs to the world, especially the world's poorest, are just too high. Also, I'm very skeptical that biofuels actually reduce CO2 emissions. The one benefit I see is that by subsidizing ethanol it may lead to innovation of other biofuels that make more sense. I hope that happens. Still, if that is the goal, a better policy would be to directly subsidize research and development, not production of the fuel itself.

7. Energy prices were a big part of the 2008 price spike, mainly due to the ethanol link. Speculation was not, as described above. Another big factor was global demand growth, much like it is today. For most of the last 75 years, growth in crop yields was faster than demand growth. That's no longer the case. Demand is growing faster than supply, and so prices are rising. It's hard to see what will reverse the new trend.

Today Krugman writes about commodity prices and makes some similar points. But I didn't know about the cotton hoarding in China. That may or may not be rational speculation--I just don't feel I know enough to venture a guess.

The journalist asked:

1. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization's index of world food prices rose 32 percent in the second half of 2010, topping the peak of June 2008. In your analysis, what are the major reasons for such a great increase in a short time?

2. In your analysis, how much does the food speculation influence current high food price?

3. Money began to be taken out of the index funds in the couple of months before food prices began to fall dramatically in mid-2008. What about the situation in 2010? If the moneys pour into the field again, why?

4. In the past 2 years after food crisis in 2008, how did the biofuel develop around the world?

5. In your analysis, how much does biofuel influence current high food price? How?

6. U.S. government makes great effort to develop biofuel. What are the government’s concerns?

7. A EU-World Bank analysis of the causes of the 2007-2008 food price crisis blames energy prices and financial speculators for the hikes. Will the same situation happen in 2011? Is there any difference between the situation in 2008 and now?I was busy at the time and so a bit late in my replies, which were as follows:

1. I think prices are rising mainly in response to increased growth and demand in the Southern Hemisphere and Asia, but particularly from China.

2. Speculation is an important part of commodity prices, but as far as I can tell, only in good ways. For example, if the market expects demand to rise in the future, prices may go up today, since some of today's production will be placed in inventories in anticipation of higher future demand. Without speculation, we wouldn't have markets trying to maneuver production from times when it is less valued to times when it will be more valued.

Note that speculation does not necessarily imply a speculative bubble. I do not think there is a speculative bubble in commodities, nor do I think has been one in recent history. I agree with the likes of Paul Krugman who has pointed out several times, that for there to be a speculative bubble in commodity prices, there needs to be a general buildup in inventories. We have not seen such a buildup in inventories. It's been quite the opposite: prices have gone up in response to declines in inventories. This is what happened in 2008 as well.

3. I don't think the money coming out of index funds has anything to do with commodity prices.

4 & 5 I think biofuel demand, artificially stimulated by government subsidies, was a big factor in the 2008 rise and one factor keeping prices high today. In my work with Wolfram Schlenker (currently under revision for the American Economic Review) we find the *long run* effect of the biofuel demand on the world's major staple commodity prices is on the order of 20-30 percent. But in the short run, the spike could have been larger. It also had the effect of drawing down inventories which made market prices far more susceptible to temporary weather or other kinds of shocks.

6. I think U.S. biofuel policy is misguided, mainly for the reasons outlined in 4&5--these costs to the world, especially the world's poorest, are just too high. Also, I'm very skeptical that biofuels actually reduce CO2 emissions. The one benefit I see is that by subsidizing ethanol it may lead to innovation of other biofuels that make more sense. I hope that happens. Still, if that is the goal, a better policy would be to directly subsidize research and development, not production of the fuel itself.

7. Energy prices were a big part of the 2008 price spike, mainly due to the ethanol link. Speculation was not, as described above. Another big factor was global demand growth, much like it is today. For most of the last 75 years, growth in crop yields was faster than demand growth. That's no longer the case. Demand is growing faster than supply, and so prices are rising. It's hard to see what will reverse the new trend.

Today Krugman writes about commodity prices and makes some similar points. But I didn't know about the cotton hoarding in China. That may or may not be rational speculation--I just don't feel I know enough to venture a guess.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

A different kind of commodity price boom

The other day I wrote that even blind optimism doesn't imply declining resource prices. Let me try to flesh that idea out a little.

A key idea in natural resource economics, called Hotelling's rule, says that non-renewable resource prices (oil, natural gas, coal, etc) should rise at about the rate of interest. The basic idea is that natural resources held in the ground and not sold need to earn a fair return, just like any other asset.

That hasn't happened. The long-run trend has been flat or downward (the last few years exempted).

Most economists have argued that the reason prices haven't increased is because extraction costs have declined. There have also been some complicated stories about depletion effects on extraction costs. These cost-related factors are very important for individual extracting firms, and may explain falling prices for a little while. But costs cannot really reconcile broad resource price trends with Hotelling's rule, which actually holds up pretty well, even with complex cost functions and rapid technological change (see this paper for technical detail of this important yet obscure and often overlooked point).

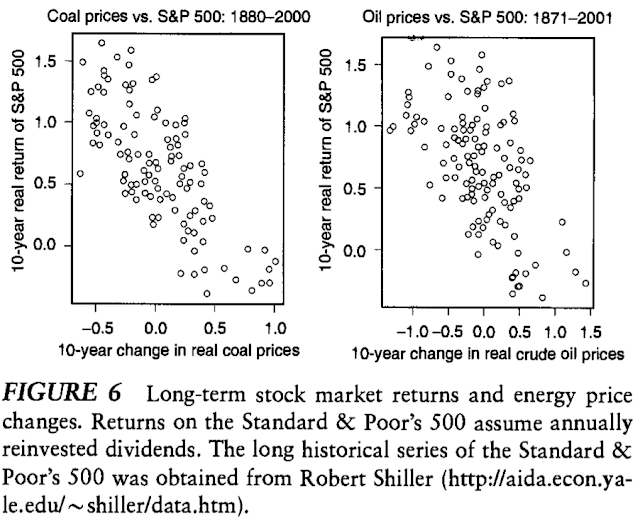

In my rapidly aging (and unpublished) dissertation, I argued that a key reason prices haven't trended up is because prices have covaried negatively with the stock market and the aggregate economy. Here are two illustrations of this phenomenon from this (also obscure) article of mine with Peter Berck: the long-run relationships oil price changes and coal price changes with returns of the S&P 500, both adjusted for inflation.

This suggests holding oil is a negative beta asset. Negative beta assets are quite unusual. Such assets are more like insurance than stock market bets, because they pay off most in bad times rather than good times. This means they have negative risk premiums, not a positive one like stocks. With a modestly negative adjustment for risk, Hotelling's interest rate may have been zero.

If that's been the case, it's an easy way reconcile the historical trend (or lack thereof) with the basic theory. But it's also quite possible that non-renewable resources are no longer negative beta assets. Today it seems commodity prices are moving up as the stock market and world economy move up. Prices are rising most in response to unexpectedly high growth, especially in Asia. This is a sharp contrast to past price shocks that have been driven by supply shocks or fear of impending shocks.

If natural resources are now positive-beta assets, like stocks, Hotelling's rule predicts prices will start trending up, perhaps more then ever before. But that's not a prediction of impending doom, at least not for the developed world. It just means there's more uncertainty about aggregate growth than there is about natural resource supply.

I do worry, however, about rising food prices. Not that this will much affect world GDP growth or the lives and livelihoods of most in the developed world--we'll hardly notice. Really. But the poorest third of the world, especially those living in urban places, cannot be happy at all about today's corn, soybean, wheat and rice prices.... But that's a different story.

A key idea in natural resource economics, called Hotelling's rule, says that non-renewable resource prices (oil, natural gas, coal, etc) should rise at about the rate of interest. The basic idea is that natural resources held in the ground and not sold need to earn a fair return, just like any other asset.

That hasn't happened. The long-run trend has been flat or downward (the last few years exempted).

Most economists have argued that the reason prices haven't increased is because extraction costs have declined. There have also been some complicated stories about depletion effects on extraction costs. These cost-related factors are very important for individual extracting firms, and may explain falling prices for a little while. But costs cannot really reconcile broad resource price trends with Hotelling's rule, which actually holds up pretty well, even with complex cost functions and rapid technological change (see this paper for technical detail of this important yet obscure and often overlooked point).

In my rapidly aging (and unpublished) dissertation, I argued that a key reason prices haven't trended up is because prices have covaried negatively with the stock market and the aggregate economy. Here are two illustrations of this phenomenon from this (also obscure) article of mine with Peter Berck: the long-run relationships oil price changes and coal price changes with returns of the S&P 500, both adjusted for inflation.

This suggests holding oil is a negative beta asset. Negative beta assets are quite unusual. Such assets are more like insurance than stock market bets, because they pay off most in bad times rather than good times. This means they have negative risk premiums, not a positive one like stocks. With a modestly negative adjustment for risk, Hotelling's interest rate may have been zero.

If that's been the case, it's an easy way reconcile the historical trend (or lack thereof) with the basic theory. But it's also quite possible that non-renewable resources are no longer negative beta assets. Today it seems commodity prices are moving up as the stock market and world economy move up. Prices are rising most in response to unexpectedly high growth, especially in Asia. This is a sharp contrast to past price shocks that have been driven by supply shocks or fear of impending shocks.

If natural resources are now positive-beta assets, like stocks, Hotelling's rule predicts prices will start trending up, perhaps more then ever before. But that's not a prediction of impending doom, at least not for the developed world. It just means there's more uncertainty about aggregate growth than there is about natural resource supply.

I do worry, however, about rising food prices. Not that this will much affect world GDP growth or the lives and livelihoods of most in the developed world--we'll hardly notice. Really. But the poorest third of the world, especially those living in urban places, cannot be happy at all about today's corn, soybean, wheat and rice prices.... But that's a different story.

Thursday, January 13, 2011

Tyler Cowen on Resource Prices

Even a Libertarian thinks resource prices may rise:

This is somewhat related to the thesis of my dissertation: For a long while perhaps the greatest uncertainty with resource prices had to do with supply, either physically or in its distribution. Today it seems a lot of the uncertainty is demand driven, stemming from uncertainty about growth in South America, Asia and possibly (hopefully) Africa. When demand uncertainty is greater than supply uncertainty, natural resource prices are likely to be positive beta assets. By this I mean prices will rise most following good news, like more growth in the catch up countries than expected. This is quite the opposite of past price spikes, which were linked to bad news about supply, say an embargo or war in the Middle East, which had made resources negative beta assets.

According to Hotelling's rule, to a first approximation, prices of nonrenewable resources should go up at the rate of interest. So, now with likely positive betas and higher risk-adjusted rates of return needed for resource investments, prices are likely to go up a lot more. When resource prices had negative betas, that risk-adjusted interest rate may have been close to zero. Today it's looking quite positive--yet another reason resource prices are likely to rise.

Why Julian Simon was so convinced of ever decreasing prices, I do not know. It just doesn't fall out of the basic economics. I'm not even sure it follows from blind optimism.

One doesn't need to be a Malthusian to think resource prices will rise. In fact, it's quite the opposite.How robust are Julian Simon's predictions?

Not the ones about population, the ones about falling real resource prices.

Here is a simple model: it is easier to transfer technologies of resource extraction than it is to transfer most other technologies. In other words, Nigeria has low TFP but still their oil rigs work pretty well.

If that's true, when the wealthiest economies are opening up a commanding lead in terms of living standards, real resource prices should be falling. Nigeria can supply a lot of oil without demanding very much.

When most of the growth is catch-up growth, the poor countries demand more resources but supply technologies are not racing so quickly ahead. Real resource prices are more likely to rise.

There is a long history of falling real resource prices, but is this simply reflecting the fact that the last three hundred years don't offer many periods of catch-up growth? Now, an era catch-up growth seems to be upon us. So why should we be so confident that Simon's predictions will continue to hold?

This is somewhat related to the thesis of my dissertation: For a long while perhaps the greatest uncertainty with resource prices had to do with supply, either physically or in its distribution. Today it seems a lot of the uncertainty is demand driven, stemming from uncertainty about growth in South America, Asia and possibly (hopefully) Africa. When demand uncertainty is greater than supply uncertainty, natural resource prices are likely to be positive beta assets. By this I mean prices will rise most following good news, like more growth in the catch up countries than expected. This is quite the opposite of past price spikes, which were linked to bad news about supply, say an embargo or war in the Middle East, which had made resources negative beta assets.

According to Hotelling's rule, to a first approximation, prices of nonrenewable resources should go up at the rate of interest. So, now with likely positive betas and higher risk-adjusted rates of return needed for resource investments, prices are likely to go up a lot more. When resource prices had negative betas, that risk-adjusted interest rate may have been close to zero. Today it's looking quite positive--yet another reason resource prices are likely to rise.

Why Julian Simon was so convinced of ever decreasing prices, I do not know. It just doesn't fall out of the basic economics. I'm not even sure it follows from blind optimism.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

The Right Graph Makes All the Difference

I'm a huge proponent of the idea that the right graphical presentation of data makes all the difference. Our eyes interpret mathematical data much better than reading numbers could, even if you're a mathematician. Sometimes graphs can lie, like statistics, but the the lie is usually easier to spot.

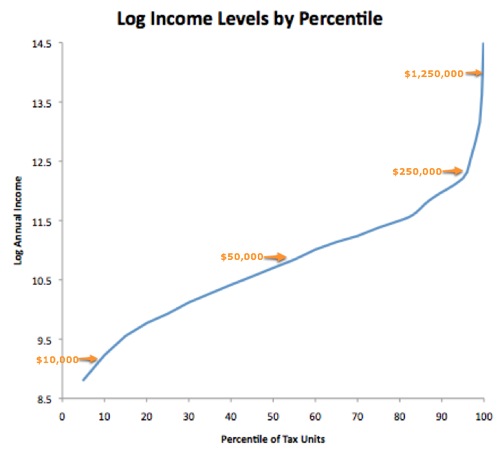

Case in point: A graph of the log income distribution and why the rich don't feel so rich, via Catherine Rampbell (always awesome), Brad Delong and Paul Krugman.

I've read zillions of statistics and have seen a lot of excellent graphs on the income distribution. But this really brings it home in a salient way. Indeed, I hadn't even realized the graph of log income looked like this. And I've seen the data a lot of times in a lot of ways.

People usually hang out with people more-or-less like themselves, in terms of income and other demographics. Now, if you make 250K/year, it's likely that a lot of your friends make twice as much or more than you do. That's a lot less likely if you make just 50K a year. So, if you're judging your income and wealth relative to your friends, you may feel much worse at 250K than you do at 50K. Or maybe even 25K/year.

Update: If you're not familiar a natural log scale, one point difference on the vertical axis, say 9.5 to 10.5, indicates a doubling of income. Also, a single "tax unit" is basically household filing a tax return.

Some say the rise in income inequality is all about education. The convexity of that graph at the upper tail tells me there's a lot more to the story.

So, I'm about to give my first lecture this semester to principles of economics students, and to tell them about the tradeoff between efficiency and equality. But these days I wonder if we can't have at least a little more of both efficiency and equity, at least as measured in utility.

Update: This also seems to help make sense of the finding in the psychological literature that suggests households with about 75K of income are happiest. Clearly, more income is better all else the same. If you have much below 75K you're, well, poorer, but the relative distribution of wealth nearby isn't much different than if you made 75K. If you go much above 75K, you're likely drooling with envy at some proportionately much, much richer friends and acquaintances, which takes away a lot of thrill of being richer.

Case in point: A graph of the log income distribution and why the rich don't feel so rich, via Catherine Rampbell (always awesome), Brad Delong and Paul Krugman.

I've read zillions of statistics and have seen a lot of excellent graphs on the income distribution. But this really brings it home in a salient way. Indeed, I hadn't even realized the graph of log income looked like this. And I've seen the data a lot of times in a lot of ways.

People usually hang out with people more-or-less like themselves, in terms of income and other demographics. Now, if you make 250K/year, it's likely that a lot of your friends make twice as much or more than you do. That's a lot less likely if you make just 50K a year. So, if you're judging your income and wealth relative to your friends, you may feel much worse at 250K than you do at 50K. Or maybe even 25K/year.

Update: If you're not familiar a natural log scale, one point difference on the vertical axis, say 9.5 to 10.5, indicates a doubling of income. Also, a single "tax unit" is basically household filing a tax return.

Some say the rise in income inequality is all about education. The convexity of that graph at the upper tail tells me there's a lot more to the story.

So, I'm about to give my first lecture this semester to principles of economics students, and to tell them about the tradeoff between efficiency and equality. But these days I wonder if we can't have at least a little more of both efficiency and equity, at least as measured in utility.

Update: This also seems to help make sense of the finding in the psychological literature that suggests households with about 75K of income are happiest. Clearly, more income is better all else the same. If you have much below 75K you're, well, poorer, but the relative distribution of wealth nearby isn't much different than if you made 75K. If you go much above 75K, you're likely drooling with envy at some proportionately much, much richer friends and acquaintances, which takes away a lot of thrill of being richer.

Monday, January 10, 2011

Food fights, price bets, and the difference between linear and exponential trends

Dot Earth just did a nice piece on my recurring focus: Food commodity prices. I found it from a link via Paul Krugman.

The long trend down in commodity prices has come about through tremendous, technology-induced growth in crop yields.

What is often overlooked, however, is that that yield growth, while impressive, has been linear. Demand growth, in contrast, has been exponential, or at least rapidly accelerating. For the last 70 years, the rate of yield growth has generally exceeded the rate of demand growth. But that accelerating demand growth has now caught up and surpassed yield growth. And so now prices are rising, not falling.

So, it's just not enough to point to historically falling prices and say that's going to continue. Show me how yield growth is going to start accelerating like demand growth. Show me how we're really going to do that and deal the detrimental effects of climate change.

The more I look at the specifics, the more I think progressively higher commodity prices are in our future.

Prospects of higher prices will surely induce greater efforts at innovation and land expansion. But we've already tapped the low hanging fruit. I'm an economist and I think supply curves slope up. Prices are going to rise.

The long trend down in commodity prices has come about through tremendous, technology-induced growth in crop yields.

What is often overlooked, however, is that that yield growth, while impressive, has been linear. Demand growth, in contrast, has been exponential, or at least rapidly accelerating. For the last 70 years, the rate of yield growth has generally exceeded the rate of demand growth. But that accelerating demand growth has now caught up and surpassed yield growth. And so now prices are rising, not falling.

So, it's just not enough to point to historically falling prices and say that's going to continue. Show me how yield growth is going to start accelerating like demand growth. Show me how we're really going to do that and deal the detrimental effects of climate change.

The more I look at the specifics, the more I think progressively higher commodity prices are in our future.

Prospects of higher prices will surely induce greater efforts at innovation and land expansion. But we've already tapped the low hanging fruit. I'm an economist and I think supply curves slope up. Prices are going to rise.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...