Lots of reports today about a plunge in corn and other food commodity prices following good news from the USDA on plantings and progress of this year's corn crop.

In just the last couple weeks corn prices have fallen from nearly $8/bushel to about $6.15. All of that is due to a rather small amount of information about the progress of this year's crop. Yes, there were reports of flooding and late plantings, but that kind of thing rarely has much effect on the overall crop production. The late plantings just set up even more volatility going forward, since the plants will be susceptible to extreme heat in July and August.

This volatility is exactly what economic models predict when inventories are low and cannot buffer weather shocks. I expect to see even larger swings in late July and August, because it's weather in these months, and particularly the amount of extreme heat in the Midwest, that will determine the size of the corn and soybean crops.

But this volatility does provide a teachable moment: it shows how sensitive prices are to small quantity changes. That sensitivity provides some indication of how much ethanol could be influencing food prices globally. And while long-run sensitivities are likely less than those in the short run, it also shows us how sensitive food commodity prices could be to even modest climate change impacts on US and world agriculture.

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

I Lean Dismal, But I'm Not a Malthusian

Following his big New York Times piece of food supply, demand and climate change, Justin Gillis has followed up with a series nice blog posts on the Times' blog called Green.

Here are the links:

Reverent Malthus and the Future of Food

Can the Yield Gap Be Closed--Sustainably?

Answering Questions About the World's Food Supply

F.A.O. Sees Stubbornly High Food Prices

World Food Supply: What's To Be Done?

These are nice articles and I highly recommend all of them.

In putting all the pieces together, I think it's important to see how different the current and potentially catastrophic future problems differ from old Malthusian notions. As I've mentioned before, this is as much a global inequality problem as it is a food supply problem.

Economists have long complained about Malthusian types like Paul Erlich because they ignore or downplay the role of prices and incentives. Economists have a good point: if food commodity prices get high enough I believe it's clear we'll have the ability to produce plenty of food. We could probably even grow that food with a lot less pollution byproducts. But to produce that much food "sustainably" would require food prices so much higher than they are today. And if food prices get that high, we'll be in solidly dismal territory for the world's poorest.

So there's the rub: Price response works real nice if we're all relatively rich. The problem is food commodity prices are so low they are basically ignored by consumers in rich countries. But those prices are still high enough that a third of the world struggles to buy enough to meet basic needs. This sits at the crux of why are not going to solve the world's food problems by having the relatively wealthy eat less meat.

Rubbing more salt in that wound is the uncomfortable fact that the historic path to development has been, at least implicitly, through cheap food. I do think it's possible that high prices could be the catalyst for positive change in some places. But it's already clear that institutional changes in the Middle East and North Africa are going to be slow and painful. It's hard for me to be especially optimistic about the institutional and economic progress of poor countries in an environment with high and rising food prices.

I firmly believe that adapting to climate change (at least with regard to food production) would be relatively easy if everyone were as rich as the United States. But that's not the world we live in.

Here are the links:

Reverent Malthus and the Future of Food

Can the Yield Gap Be Closed--Sustainably?

Answering Questions About the World's Food Supply

F.A.O. Sees Stubbornly High Food Prices

World Food Supply: What's To Be Done?

These are nice articles and I highly recommend all of them.

In putting all the pieces together, I think it's important to see how different the current and potentially catastrophic future problems differ from old Malthusian notions. As I've mentioned before, this is as much a global inequality problem as it is a food supply problem.

Economists have long complained about Malthusian types like Paul Erlich because they ignore or downplay the role of prices and incentives. Economists have a good point: if food commodity prices get high enough I believe it's clear we'll have the ability to produce plenty of food. We could probably even grow that food with a lot less pollution byproducts. But to produce that much food "sustainably" would require food prices so much higher than they are today. And if food prices get that high, we'll be in solidly dismal territory for the world's poorest.

So there's the rub: Price response works real nice if we're all relatively rich. The problem is food commodity prices are so low they are basically ignored by consumers in rich countries. But those prices are still high enough that a third of the world struggles to buy enough to meet basic needs. This sits at the crux of why are not going to solve the world's food problems by having the relatively wealthy eat less meat.

Rubbing more salt in that wound is the uncomfortable fact that the historic path to development has been, at least implicitly, through cheap food. I do think it's possible that high prices could be the catalyst for positive change in some places. But it's already clear that institutional changes in the Middle East and North Africa are going to be slow and painful. It's hard for me to be especially optimistic about the institutional and economic progress of poor countries in an environment with high and rising food prices.

I firmly believe that adapting to climate change (at least with regard to food production) would be relatively easy if everyone were as rich as the United States. But that's not the world we live in.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

A Warming Planet Struggles to Feed Itself

The subject heading is the title of the front page article by Justin Gillis in this morning's New York Times. It's a long multi-page feature. It begins:

I had one long phone conversation with Justin Gillis about this piece. It was awhile back. He had spoken with everyone and visited the major research centers. By the time he spoke with me he really knew his stuff. It's nice work. And it's nice to see this issue get front page billing.

I'm mentioned with Wolfram Schlenker in the section "Shaken Assumptions".

CIUDAD OBREGÓN, Mexico — The dun wheat field spreading out at Ravi P. Singh’s feet offered a possible clue to human destiny. Baked by a desert sun and deliberately starved of water, the plants were parched and nearly dead.

Dr. Singh, a wheat breeder, grabbed seed heads that should have been plump with the staff of life. His practiced fingers found empty husks.

“You’re not going to feed the people with that,” he said.

But then, over in Plot 88, his eyes settled on a healthier plant, one that had managed to thrive in spite of the drought, producing plump kernels of wheat. “This is beautiful!” he shouted as wheat beards rustled in the wind.

Hope in a stalk of grain: It is a hope the world needs these days, for the great agricultural system that feeds the human race is in trouble.

The rapid growth in farm output that defined the late 20th century has slowed to the point that it is failing to keep up with the demand for food, driven by population increases and rising affluence in once-poor countries.

Consumption of the four staples that supply most human calories — wheat, rice, corn and soybeans — has outstripped production for much of the past decade, drawing once-large stockpiles down to worrisome levels. The imbalance between supply and demand has resulted in two huge spikes in international grain prices since 2007, with some grains more than doubling in cost.Those price jumps, though felt only moderately in the West, have worsened hunger for tens of millions of poor people, destabilizing politics in scores of countries, from Mexico to Uzbekistan to Yemen. The Haitian government was ousted in 2008 amid food riots, and anger over high prices has played a role in the recent Arab uprisings.

Now, the latest scientific research suggests that a previously discounted factor is helping to destabilize the food system: climate change.Many of the failed harvests of the past decade were a consequence of weather disasters, like floods in the United States, drought in Australia and blistering heat waves in Europe and Russia. Scientists believe some, though not all, of those events were caused or worsened by human-induced global warming.

Temperatures are rising rapidly during the growing season in some of the most important agricultural countries, and a paper published several weeks ago found that this had shaved several percentage points off potential yields, adding to the price gyrations.

...

I'm mentioned with Wolfram Schlenker in the section "Shaken Assumptions".

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Price to rent ratio and interest rates

No time for thoughtful on-topic posts these days. Hopefully one sleepless night soon.

Here's a quickie on one of my favorite off-topic subjects:

Bill McBride at Calculated Risk reports that the national price-to-rent ratio is back to 1999 levels. That's well before the bubble took hold. For those who look only at this ratio as a guide to home prices, that's probably a sign that prices have reverted to fundamentals.

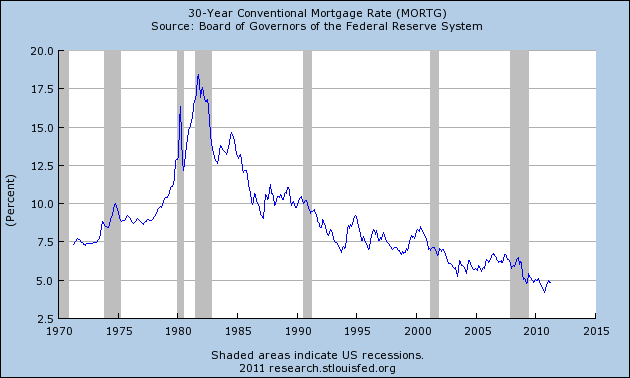

But consider today's interest rates compared to 1999:

Today we're looking at a 30 year mortgage rate that is about two-thirds the level in 1999.

I'd say that makes prices today look like a really good deal, especially given anecdotal evidence that rents are on the rise. When the economy does truly recover, those buying homes today will do very well.

Beneath national averages there is tremendous variation in price-to-rent ratios. In some areas home prices are much more attractive than others. That means home prices are a screaming deal in some places. Yet home prices are still falling.

I don't mean to give investment advice as much as point out how far off prices seem to be from fundamentals. I'd say our problems with debt deleveraging and irrational pessimism remain quite severe.

Here's a quickie on one of my favorite off-topic subjects:

Bill McBride at Calculated Risk reports that the national price-to-rent ratio is back to 1999 levels. That's well before the bubble took hold. For those who look only at this ratio as a guide to home prices, that's probably a sign that prices have reverted to fundamentals.

But consider today's interest rates compared to 1999:

Today we're looking at a 30 year mortgage rate that is about two-thirds the level in 1999.

I'd say that makes prices today look like a really good deal, especially given anecdotal evidence that rents are on the rise. When the economy does truly recover, those buying homes today will do very well.

Beneath national averages there is tremendous variation in price-to-rent ratios. In some areas home prices are much more attractive than others. That means home prices are a screaming deal in some places. Yet home prices are still falling.

I don't mean to give investment advice as much as point out how far off prices seem to be from fundamentals. I'd say our problems with debt deleveraging and irrational pessimism remain quite severe.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...