Angus Deaton just

won the Nobel Prize in economics. He's a brilliant, famous economist who is known for

many contributions. In graduate school I discovered a bunch of his papers and studied them carefully. He is a clear and meticulous writer which made it easy for me to learn a lot of technical machinery, like stochastic dynamic programming. His care and creativity in statistical matters, and linking data to theory, was especially inspiring. His papers with Christina Paxson inspired me to think long and hard about all the different ways economists might exploit weather as an instrument for identifying important economic phenomena.

One important set of contributions about which I've seen little mention concerns a body of work on commodity prices that he did in collaboration with Guy Laroque. This is really important research, and I think that many of those who do agricultural economics and climate change might have missed some of its implications, if they are aware of it at all.

Deaton lays out his work on commodity prices like he does in a lot of his papers: he sets out to test a core theory, insists on using only the most reliable data, and then pushes the data and theory hard to see if they can be reconciled with each other. He ultimately concludes that, while theory can broadly characterize price behavior, there is a critical paradox in the data that the theory cannot reconcile: too much autocorrelation in prices. (ASIDE 1)

These papers are quite technical and the concluding autocorrelation puzzle is likely to put most economists, and surely all non-economists, into a deep slumber. Who cares?

Undoubtedly, a lot of the fascination with these papers was about technique. They were written in the generation following discovery of GMM (generalized method of moments) as a way to estimate models centered on rational expectations, models in which iid errors can have an at least somewhat tangible interpretation as unpredictable "expectation errors."

One thing I always found interesting and useful from these papers was something that Deaton and Larqoue take entirely for granted. They show that the behavior of commodity prices themselves, without any other data, indicate that their supply and demand are extremely inelastic. (ASIDE 2) For, if they weren't, prices would not be as volatile as they are, as autocorrelated as they are, and stored as prevalently as they are. Deaton writes as much in a number of places, but states this as if it's entirely obvious and not of critical concern. (ASIDE 3)

But here's the thing: the elasticities of supply and demand are really what's critical for thinking about implications of policies, especially those that can affect supply or demand on a large scale, like ethanol mandates and climate change. Anyone who read and digested Deaton and Laroque and knew the stylized facts about corn prices knew that the ethanol subsidies and mandates were going to cause food prices to spike, maybe a whole lot. But no one doing policy analysis in those areas paid any attention.

Estimated elasticities regularly published in the AJAE for food commodities are typically orders of magnitude larger than are possible given what is plainly clear in price behavior, and the authors typically appear oblivious to the paradox. Also, if you like to think carefully about identification, it's easy to be skeptical of the larger estimated elasticities. Sorry aggies--I'm knocking you pretty hard here and I think it's deserved. I gather there are similar problems in other corners of the literature, say mineral and energy economics.

And it turns out that the autocorrelation puzzle may not be as large a puzzle as Deaton and Laroque let on. For one, a little refinement of their technique can give rise to greater price autocorrelation, a refinement that also implies even more inelastic supply and demand. Another simple way to reconcile theory and data is to allow for so-called ``convenience yields," which basically amounts to negative storage costs when inventories are low. Negative storage costs don't make sense on their face, but might actually reflect the fact that in any one location---where stores are actually held---prices or the marginal value of commodities can be a lot more volatile than posted prices in a market. Similar puzzles of positive storage when spot prices exceed futures prices can be similarly explained---there might be a lot of uncertain variability in time and space that sit between stored inventories and futures deliveries.

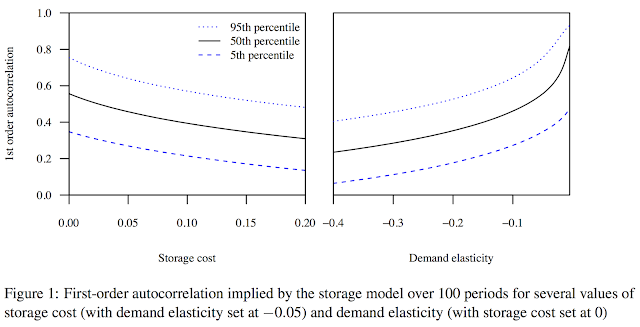

The graph below, from this recent paper by

Gouel and Legrand, uses updated techniques to show how inelastic demand needs to be to obtain high price autocorrelation, as we observe in the data (typically well above 0.6).

Adding bells and whistles to the basic theory easily reconciles the puzzle, but only strengthens the conclusion that demand and supply of commodities are extremely steep. And that basic conclusion should make people a little more thoughtful when it comes to thinking about implications of policies and about the potential impacts of climate change, which could greatly disrupt supply of food commodities.

ASIDE 1: Papers like Deaton's differ from most of the work that fills up the journals these days. Today we see a lot more empirical work than in the past, but most of this work is nearly atheoretical, at least relative to Deaton's. It most typically follows what

David Card describes as ``the design-based approach." I don't think that's bad change. But I think there's a lot of value in the kind of work Deaton did, too.

ASIDE 2: The canonical model that Deaton and Laroque use, and much of the subsequent literature, has a perfectly inelastic supply curve that shifts randomly with the weather and a fixed demand curve. This is because, using only prices, one cannot identify both demand and supply. Thus, the estimated demand elasticities embody

both demand and supply. And since that one elasticity is clearly very inelastic it also implies the sum of the two elasticities is very inelastic.

ASIDE 3: Lots of people draw conclusions lightly as if they are obvious without really thinking carefully about lies beneath. Not Angus Deaton.