This comes from Real Climate, or more specifically, from Steven Levitt's colleague at the University of Chicago: Raymond T. Pierrehumbert, Louis Block Professor in the Geophysical Sciences.

OUch. It makes me utterly ashamed to be an economist.

Update: Joe Romm is relentless. It seems to me Levitt and Dubner should have eaten copious quantities of humble pie on day one. They didn't. Why not?

Maybe because they aren't quite the hard-headed objectivists they paint themselves to be? Here are some interesting musings from Andrew Gelman on the role of ideology the likely underlies a lot of this, and especially its internal contradictions.

Saturday, October 31, 2009

Friday, October 30, 2009

Counting jobs

Okay, I'm not a macroeconomist, so someone please tell me if I way off base here. I'm trying to figure out how reasonable or unreasonable the Obama administration's claim of 1 million jobs saved may be.

The media reports are useless. We all know that every journalist can find a Republican that says it's all bogus and the Obama administration will stand by its numbers. Sadly, none of the news reports walk through the Econ 1 and basic algebra to weigh in on the reasoning underlying the numbers. Bad reporting or stupid reporters? Which is it?

Anyway....

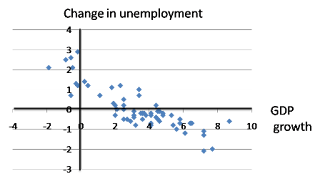

So, as an armchair macro guy I'll borrow Krugman's picture of Okun's law. It shows we get an extra 0.5% change in unemployment for every 1% change in GDP. There are about 150 million jobs in the U.S. so 0.5% is about 750K jobs.

So, in claiming 1 million jobs created or saved, the Obama administration is claiming GDP is about 1.33% larger than it would have been without the stimulus.

Now we have this table from the Economic Policy Institute that, in the first three quarters of 2009, found growth was about 0.3, 2.4, and 2.3 percentage points greater due to stimulus. These are quarterly rates, so we have to divide the sum by 4, which gives us an economy that is about 1.25% greater than it would have been. Now, we're a little ways into the four quarter, so maybe it's okay to fudge things upward by another 2.3/12 or so, to put this up to about 1.45.

Maybe not. You decide. In any case, we're looking at something a little less to a bit more than a million jobs by standard macro calculations. And this does look like a standard macro Keynesian boost.

While this sort of thing is generally difficult to pin down, to me a million jobs looks reasonable. If there's fudging going on, someone please tell me where and how.

Update: Brad Delong explains how to count the costs and benefits. I imagine some would quibble around the edges with his specific numbers. But he has all the right pieces and the numbers can't be far from correct. Also, I think he's assuming a multiplier of 1 when something on the order of 1.5 is probably easy to justify.

The media reports are useless. We all know that every journalist can find a Republican that says it's all bogus and the Obama administration will stand by its numbers. Sadly, none of the news reports walk through the Econ 1 and basic algebra to weigh in on the reasoning underlying the numbers. Bad reporting or stupid reporters? Which is it?

Anyway....

So, as an armchair macro guy I'll borrow Krugman's picture of Okun's law. It shows we get an extra 0.5% change in unemployment for every 1% change in GDP. There are about 150 million jobs in the U.S. so 0.5% is about 750K jobs.

So, in claiming 1 million jobs created or saved, the Obama administration is claiming GDP is about 1.33% larger than it would have been without the stimulus.

Now we have this table from the Economic Policy Institute that, in the first three quarters of 2009, found growth was about 0.3, 2.4, and 2.3 percentage points greater due to stimulus. These are quarterly rates, so we have to divide the sum by 4, which gives us an economy that is about 1.25% greater than it would have been. Now, we're a little ways into the four quarter, so maybe it's okay to fudge things upward by another 2.3/12 or so, to put this up to about 1.45.

Maybe not. You decide. In any case, we're looking at something a little less to a bit more than a million jobs by standard macro calculations. And this does look like a standard macro Keynesian boost.

While this sort of thing is generally difficult to pin down, to me a million jobs looks reasonable. If there's fudging going on, someone please tell me where and how.

Update: Brad Delong explains how to count the costs and benefits. I imagine some would quibble around the edges with his specific numbers. But he has all the right pieces and the numbers can't be far from correct. Also, I think he's assuming a multiplier of 1 when something on the order of 1.5 is probably easy to justify.

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Menzie Chin on futures as predictors of commodity prices

Here is Menzie Chin (my thoughts below):

This is a topic that has long interested me. Fama and French have an earlier piece that looks at this same issue, albeit framed somewhat differently.

In theory, the expected difference between the futures price and spot price is a risk premium. The risk premium for precious metals and natural gas appears to be negative. That is, locking in the price today (removing risk) typically means a higher price as well. If you're making these goods then selling short is a no-brainer. There don't seem to be any positive risk premiums. That is, storing your goods to sell later [without selling short on the futures market] is a risk that pays no reward for any commodity.

So why would the risk premia be negative? One possibility is that these commodities are key inputs to the aggregate economy and price variability comes mainly from supply shocks. That was probably once true for oil but now it seems demand shocks are driving things, which reverses the risk premium (see work by Killian). Alternatively, they can serve as a hedge against financial and economic meltdown. That means buying commodities (going long) is what the market does to reduce their overall exposure to risk.

My dissertation, which I never published, argued that these negative risk premiums help to explain why natural resource prices haven't trended up over time. A negative adjustment for risk means Hotelling's interest rate is probably close to zero.

I'm a little less confident than I used to be about this story. But I still think there is some truth to it. I really need to dust off that paper...

As commodity prices start rising again -- at least some -- the question of whether futures are useful indicators seems relevant. Figure 1 shows the IMF commodity price indices, as reported in the October World Economic Outlook:

Figure 1: Commodity price indices for energy (blue), food (red), agricultural raw materials (green), metals (black) and beverages (teal). NBER defined recession shaded gray, assuming recession ends in 2009M06. Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook (October 2009), data for Chart 1.16.

In a previous set of papers, Oli Coibion, Michael LeBlanc and I examined the predictive power of energy futures post and paper.

In a new paper, Oli Coibion and I update our results regarding energy futures, and metal and agricultural commodities as well, through the end of August 2008, just before the financial crisis broke out in full force. From the paper:

This paper examines the relationship between spot and futures prices for commodities, including those for energy (crude oil, gasoline, heating oil markets and natural gas), precious and base metals (gold, silver, aluminum, copper, lead, nickel and tin), and agricultural commodities (corn, soybean and wheat). In particular, we examine whether futures prices are (1) an unbiased and/or (2) accurate predictor of subsequent spot prices. We find that while energy futures prices are generally unbiased predictors of future spot prices, there are certain notable exceptions. For both base and precious metals, the results are much less favorable to unbiasedness hypothesis. For precious metals and copper and lead, we strongly reject the null that β=1 at all three horizons. For the these other base metals, while we cannot reject that β=1, due to large standard errors. Finally, both corn and soybean futures have β close to 1, while wheat has β<1. Excepting oil and base metals, futures tend to outperform a random walk specification in out of sample forecasts.

The regression we run is:

st - st-k = β 0 + β 1 (f t|t-k - st-k) + ε t

Where st is the log spot price at time t, ft|t-k is the log futures price at time t-k that matures at time t. The resulting β coefficients at the three month horizons are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: β1 coefficients, estimated via OLS. *** denotes significantly different from unity at the 1% level, using HAC robust standard errors. Source: Author's calculations.

Despite the bias in futures, along a RMSE dimension, futures outperform a random walk for most commodities, except for base metals (the out of sample period is 03M01 to 08M07). That being said, the outperformance relative to a random walk is seldom statistically significant.

This is a topic that has long interested me. Fama and French have an earlier piece that looks at this same issue, albeit framed somewhat differently.

In theory, the expected difference between the futures price and spot price is a risk premium. The risk premium for precious metals and natural gas appears to be negative. That is, locking in the price today (removing risk) typically means a higher price as well. If you're making these goods then selling short is a no-brainer. There don't seem to be any positive risk premiums. That is, storing your goods to sell later [without selling short on the futures market] is a risk that pays no reward for any commodity.

So why would the risk premia be negative? One possibility is that these commodities are key inputs to the aggregate economy and price variability comes mainly from supply shocks. That was probably once true for oil but now it seems demand shocks are driving things, which reverses the risk premium (see work by Killian). Alternatively, they can serve as a hedge against financial and economic meltdown. That means buying commodities (going long) is what the market does to reduce their overall exposure to risk.

My dissertation, which I never published, argued that these negative risk premiums help to explain why natural resource prices haven't trended up over time. A negative adjustment for risk means Hotelling's interest rate is probably close to zero.

I'm a little less confident than I used to be about this story. But I still think there is some truth to it. I really need to dust off that paper...

On the commodity share of retail food prices

A professor of biological sciences emails:

In case others are interested, here's my reply:

I believe the general principle is well known. The numbers in the quote came from my own back-of-the-envelope calculations. There are about 6 lbs. of corn used to produce each lb. of beef. Corn sells for about $3.70/bushel. A bushel is 56 lbs. So I figured the value of corn in a pound of beef was about 40 cents, or 10 cents in a quarter pound hamburger. If corn went up to $37.00, a lot of people in poor countries would starve to death. But the price of a burger would go up just 90 cents.

A few key economic concepts to keep in mind: Markets for raw commodities are extremely competitive, meaning that individual buyers and sellers really don't have any control over the prices they pay or receive. Things are different at later stages in the process from raw commodities to retail. Some buyers (like Walmart) have a lot of market power. Also, usually an individual store can adjust retail prices up without losing all their customers or adjust prices down without instantly selling everything they have. These basic ideas suggest that retail food prices would probably go up less than the change in commodity value contained in the retail food.

Also, empirically, retail prices tend vary less than wholesale prices in absolute terms. In other words, I was being conservative--a pound of beef would probably go up a lot less than 90 cents.

USDA ERS (Economic Research Service) has a few studies looking at prices at different steps along the retail path.

Authors doing recent research in this area include Ephraim Leibtag and Emi Nakamura. If you google those names and "pass through" you should find some interesting stuff.

I would like to follow up on your observation that "Raw commodities make up such a tiny share of retail food prices we would hardly notice a 10-fold increase in corn prices. The price of a quarter-pound hamburger (produced from corn-fed beef) would probably go up by less than a dollar."I knew someone would ask that question...

Could you direct me to the analysis or more general treatments of the supply chain costs? At the moment, I'm very interested in supply costs and retail costs for soybean-based products. I'm a molecular scientist and not an economist, so I appologise if my request is very basic!

In case others are interested, here's my reply:

I believe the general principle is well known. The numbers in the quote came from my own back-of-the-envelope calculations. There are about 6 lbs. of corn used to produce each lb. of beef. Corn sells for about $3.70/bushel. A bushel is 56 lbs. So I figured the value of corn in a pound of beef was about 40 cents, or 10 cents in a quarter pound hamburger. If corn went up to $37.00, a lot of people in poor countries would starve to death. But the price of a burger would go up just 90 cents.

A few key economic concepts to keep in mind: Markets for raw commodities are extremely competitive, meaning that individual buyers and sellers really don't have any control over the prices they pay or receive. Things are different at later stages in the process from raw commodities to retail. Some buyers (like Walmart) have a lot of market power. Also, usually an individual store can adjust retail prices up without losing all their customers or adjust prices down without instantly selling everything they have. These basic ideas suggest that retail food prices would probably go up less than the change in commodity value contained in the retail food.

Also, empirically, retail prices tend vary less than wholesale prices in absolute terms. In other words, I was being conservative--a pound of beef would probably go up a lot less than 90 cents.

USDA ERS (Economic Research Service) has a few studies looking at prices at different steps along the retail path.

Authors doing recent research in this area include Ephraim Leibtag and Emi Nakamura. If you google those names and "pass through" you should find some interesting stuff.

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Alternatives to Biotech Food

Here are a few follow up ideas from the NYT Room for Debate. This is such a huge topic it's hard to know what to put in 300 words. I opted more for context than hard recommendations in my 300 word spiel. If I had more space I probably would have laid out these additional points:

- I don't think biotech crops are evil and could be a big help, especially in developing nations. But I think we'd be naive to think these will solve all the world's food problems going forward. Maybe they will but they probably won't.

- Good development policy, whatever that may be, is surely good food policy. In many ways food is too cheap relative to income in rich countries and too expensive relative to income in poor countries. Both problems are solved if incomes are more equal. Figuring out good development policy is, err..., much harder...

- I think a meat tax makes a lot of sense. Taxing meat would help to keep staple grains cheap and plentiful, which would help the poorest food-importing countries and probably improve health outcomes in rich countries. Some economists would probably cry foul. They might claim lump-sum transfers of cash would be a better way to deal with the underlying distributional issue. The problem is effective transfers to especially poor countries are very difficult. (Consider why those countries are poor in the first place.) Also, given our semi-public health care systems in rich countries, there could be negative externalities from meat consumption.

- Stop ethanol subsidies. These look really silly.

- Then there is that other externality we might want to tax or cap (CO2).

- I do think population growth is a concern, but one intimately tied to the broader problem of poverty and income inequality. Educate women and provide them with birth control and people live longer and countries grow richer. This touches on the most important aspects of good development policy of which I am aware.

- I think both Paul Ehrlich and Julian Simon were foolish gamblers. It's very hard to predict where prices are headed. Julian Simon was simply lucky. From here on I can see both dismal and relatively utopian futures as distinctly possible.

- While dismal outcomes are possible, they are not Malthusian. We have birth control today. The economic tensions are very different from those described by Malthus.

Monday, October 26, 2009

Climate change, food supply and the role of genetically modified crops

I think higher food prices--the kind the poor will see much more than anyone reading this blog post--are one of the biggest risks from global warming. If you don't care about whether the poor eat or not, I think you will care about the civil conflict that would accompany their hunger. If GMOs solve the problem, great. But I'm kinda skeptical that they will...

Here I am live at the New York Times Room for Debate:

Here I am live at the New York Times Room for Debate:

About 30 years ago Julian Simon, an economist, made a famous bet with Paul Ehrlich, the entomology professor and author of “The Population Bomb.” The bet was about the future direction of resource prices.

Where Mr. Ehrlich saw population growth leading to scarcity in resources and higher prices, Mr. Simon saw an impending resource boom that would easily compensate for population growth. Mr. Simon handily won the bet.

Staple commodity prices — from food to oil to metals — have all trended flat or downward over the long run. Technological optimists point to this fact and believe resource scarcity is of little concern to our post-industrial society. In a sense, they’re right. But what about the part of the world that isn’t industrialized?

I am mindful of arguments coming from technological optimists who believe crop yields will continue to rise, that there is plenty of oil still left to find and that geo-engineering will solve global warming.

But I don’t think today’s doomsayers are a few voices in small corners of the scientific community. There is a real threat to worldwide food security over the next 10 to 40 years. The threat comes from global income inequality combined with projected global warming, which could cause tremendous declines in crop yields.

For the United States — by far the world’s largest producer and exporter of food commodities — my own statistical research with Wolfram Schlenker predicts yield declines of 18 percent to 35 percent for corn and soybeans due to global warming, and more than twice these losses by the end of this century.

A recent, far more comprehensive study by the International Food Policy Research Institute predicts large food production declines and higher prices for the whole world.

For people in the United States these dramatic predictions are actually of little direct concern. Raw commodities make up such a tiny share of retail food prices we would hardly notice a 10-fold increase in corn prices. The price of a quarter-pound hamburger (produced from corn-fed beef) would probably go up by less than a dollar. It’s hard to believe we’d buy much less meat as a result. Indeed, demand growth today comes less from population growth and more from rising incomes and meat consumption in China. (Keep in mind that it takes five to 10 calories of staple grains to make one calorie of meat.)

But three billion people — nearly half the planet — live on $2.50 per day or less. The poor typically spend a third to half of their income on food, composed mainly of staple commodities. If food quantities go down and prices go up, it’s the world’s poor who consume less.

If incomes were more equal around the world, prices would rise much further and we would buy less meat, but there would be little risk of famine.

Still, it could be that new genetically modified seeds will accelerate yield growth and offset projected damages from global warming. So far, genetically modified crops have shown yield gains in developing nations, but only modest gains in rich countries. And though yields have grown, my research shows no growth in tolerance to extreme heat, which is the key challenge going forward.

The green revolution didn’t come about from a wondrous market. It came from public investments in crop science that people like Norman Borlaug then spread around the world. But public funding of crop science research has diminished over the years. Now seems like a good time to increase that kind of investment.Update: I put a few further policy recommendations here.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Mark Thoma asks if there is a solution to the Pundit's Delimma

Here's Mark Thoma:

Yeah, I think so. But why? Probably because it pays more that it did in the past. So why does it pay more today than it used to?

Telling it good and telling it straight is a long-term strategy. That strategy was possible under old profit models of broadcast news and a few key print media sources. In the long run, lies would be punished with smaller audiences, circulations, and advertising dollars.

But today, with an increasingly fractured media comprised of a zillion outlets sharing fewer advertising dollars, and the internet spreading news free of charge, the long view no longer pays. Old profit models no longer work and everyone is grasping. All of this makes the media business short-sighted, because odds are better than not that any one of them won't be around long enough to reap the long-term benefits of telling it good and telling it straight.

I think this problem may well resolve itself, but it will take time. We're in transition. If and when the media business settles down into a new paradigm and it becomes clear who will stick around and what their business models will look like, the incentive to take a longer view will be restored. And at least some of what we see, hear and read will be worth seeing, hearing, and reading.

Or so I hope.

Update: I do find marvelously hopeful the quick and thorough debunking of the Superfreakonomics chapter on climate change. The media of yesteryear couldn't do that. Joe Romm, Paul Krugman, and especially Brad Delong, among many others, have done a wonderful public service here.

Another Update: Despite his promise not to, Delong came along with more excellent criticism of Superfreak. Some pretty good substance in the comments, too.

Mark Liberman at Language Log says the game theory can explain why pundits "best move always seems to be to take the low road":

...Overall, the promotion of interesting stories in preference to accurate ones is always in the immediate economic self-interest of the promoter. It's interesting stories, not accurate ones, that pump up ratings for Beck and Limbaugh. But it's also interesting stories that bring readers to The Huffington Post and to Maureen Dowd's column, and it's interesting stories that sell copies of Freakonomics and Super Freakonomics. In this respect, Levitt and Dubner are exactly like Beck and Limbaugh.

We might call this the Pundit's Dilemma — a game, like the Prisoner's Dilemma, in which the player's best move always seems to be to take the low road, ....

Is media becoming increasingly crass? Are scholars and intellectuals increasingly aiding and abetting the debasement of information?...Pundits (and regular journalists) also play an iterated version of this game — but empirical observation suggests that the penalties for many forms of bad behavior are too small and uncertain to have much effect. Certainly, the reputational effects of mere sensationalism and exaggeration seem to be negligible. ...I think it's correct that the penalties pundits face for "many forms of bad behavior are too small and uncertain to have much effect," but I'm not sure that was always true to the extent it's true today. So the question to me is why the tolerance for this behavior has changed over time (has it changed?).... ....Is there a solution?

Yeah, I think so. But why? Probably because it pays more that it did in the past. So why does it pay more today than it used to?

Telling it good and telling it straight is a long-term strategy. That strategy was possible under old profit models of broadcast news and a few key print media sources. In the long run, lies would be punished with smaller audiences, circulations, and advertising dollars.

But today, with an increasingly fractured media comprised of a zillion outlets sharing fewer advertising dollars, and the internet spreading news free of charge, the long view no longer pays. Old profit models no longer work and everyone is grasping. All of this makes the media business short-sighted, because odds are better than not that any one of them won't be around long enough to reap the long-term benefits of telling it good and telling it straight.

I think this problem may well resolve itself, but it will take time. We're in transition. If and when the media business settles down into a new paradigm and it becomes clear who will stick around and what their business models will look like, the incentive to take a longer view will be restored. And at least some of what we see, hear and read will be worth seeing, hearing, and reading.

Or so I hope.

Update: I do find marvelously hopeful the quick and thorough debunking of the Superfreakonomics chapter on climate change. The media of yesteryear couldn't do that. Joe Romm, Paul Krugman, and especially Brad Delong, among many others, have done a wonderful public service here.

Another Update: Despite his promise not to, Delong came along with more excellent criticism of Superfreak. Some pretty good substance in the comments, too.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Bad for yields does not mean bad for farmers' profits

Yes, we do predict large negative impacts to U.S. crop yields from global warming. Yes, there are many reasons why things might not get as bad as we predict. But the evidence, I think, is pretty clearly bad for crop yields.

So, in response to Grist and the position by the American Farm Bureau on climate change, one may wonder: Why would farmers oppose the climate bill if they have so much to lose from potential global warming?

There is a simple answer: a big hit to crop yields does not imply a big hit to farmers' profits. In fact, if the rest of the world is unable to make up for U.S. losses, a big hit to yields is probably a very good thing for farmers profits. At least for the corn-soybean guys in the Midwest.

You see, the demand curve for basic grains is very steep. We've estimated an elasticity of about 0.05 (also see this paper). So if yields worldwide get cut by 50%, and no additional supply comes online to replace that loss, prices will go up 1000%, and farmers revenues will go up 500%. Farmers' profits will go up by a lot more than 500%.

So, while climate change is looking bad for buyers of basic grains, like North Carolina hog farmers and the urban poor in developing nations, those who grow basic grains will do very well. The incentives are very clear: opposing climate change legislation is good for corn growers' pocketbooks.

So, in response to Grist and the position by the American Farm Bureau on climate change, one may wonder: Why would farmers oppose the climate bill if they have so much to lose from potential global warming?

There is a simple answer: a big hit to crop yields does not imply a big hit to farmers' profits. In fact, if the rest of the world is unable to make up for U.S. losses, a big hit to yields is probably a very good thing for farmers profits. At least for the corn-soybean guys in the Midwest.

You see, the demand curve for basic grains is very steep. We've estimated an elasticity of about 0.05 (also see this paper). So if yields worldwide get cut by 50%, and no additional supply comes online to replace that loss, prices will go up 1000%, and farmers revenues will go up 500%. Farmers' profits will go up by a lot more than 500%.

So, while climate change is looking bad for buyers of basic grains, like North Carolina hog farmers and the urban poor in developing nations, those who grow basic grains will do very well. The incentives are very clear: opposing climate change legislation is good for corn growers' pocketbooks.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

Ezra Klein on climate change and agriculture

Here's a first for me: I'm quoted in the Washington Post! And so is this wee little blog.

Kudos and thanks to Ezra Klein for writing about implications of global warming on crop yields. The big study by IFPRI was the main focus, as it should have been, but he also wrote a bit about our study.

Two little quibbles:

(1) Our temperature threshold of 84F is actually the optimal temperature for corn. It gets bad pretty quickly for temperature much hotter than that, but a little hotter is still okay. Much above 90 is bad, but it depends on how long it stays that hot. Anyway, I probably could have been clearer about this in my earlier blog posts.

(2) I'm still a lowly assistant professor, not Professor, despite my rapidly advancing age. You see, I'm new to the academic thing. Just over a year ago I was a government bureaucrat at the USDA.

But thank you kindly for the exposure Ezra, it's much appreciated.

Kudos and thanks to Ezra Klein for writing about implications of global warming on crop yields. The big study by IFPRI was the main focus, as it should have been, but he also wrote a bit about our study.

Two little quibbles:

(1) Our temperature threshold of 84F is actually the optimal temperature for corn. It gets bad pretty quickly for temperature much hotter than that, but a little hotter is still okay. Much above 90 is bad, but it depends on how long it stays that hot. Anyway, I probably could have been clearer about this in my earlier blog posts.

(2) I'm still a lowly assistant professor, not Professor, despite my rapidly advancing age. You see, I'm new to the academic thing. Just over a year ago I was a government bureaucrat at the USDA.

But thank you kindly for the exposure Ezra, it's much appreciated.

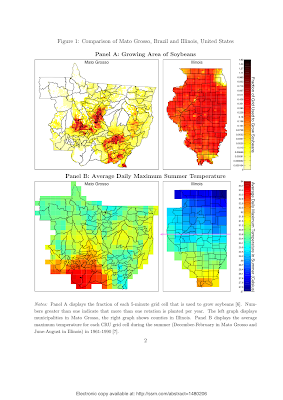

Growing Areas in Brazil and the United States with Similar Exposure to Extreme Heat Have Similar Yields

Update: The letter to PNAS by Meerburg et. al is here. Our reply is here.

Boy, that was fast.

Less than three weeks after PNAS published Wolfram Schlenker’s and my paper predicting big negative impacts from global warming on U.S. corn, soybean and cotton yields, we were notified about a letter to the editor commenting on our article. The PNAS editors had already agreed to publish the letter when they told us about it. We had seven days to write a maximum 500-word reply.

The jist their letter: It’s already hotter in Brazil than the United States, and some areas of Brazil have higher yields than the United States, so we were being too “pessimistic” about what might happen to U.S. yields. More precisely, they claimed 2008 soybean yields in the Brazilian state of Mato Grasso were higher than U.S. yields of that year.

Hmmmm. Well, we didn’t claim our results extended to Brazil. Brazil differs from the U.S. in many ways. For one, Brazil is a lot closer to the equator, which makes sunlight exposure markedly different. Both countries are also quite large. The U.S., like Brazil, has widely varying temperatures and crop yields. So, to our way of thinking, such a comparison really deserves more careful thought and analysis than a drive-by letter to the editor.

We didn’t understand the statistics given by the commenters, so we did a little digging of our own. Mind you, we didn’t have time for a full-blown study. But here’s what we found:

First, they cherry picked the state and the year from Brazil. Mato Grasso is the highest yielding state in Brazil and 2008 was a remarkably good year for them, due to unusually good weather. Other states in Brazil have average yields that are about half those of Mato Grasso.

Second, Mato Grasso yields were higher than average yields in the U.S. as a whole, but not higher than the best yielding states in the U.S.

Third, if we narrow our comparison by looking a particular state—Illinois, the number two yielding soybean state in the U.S.—and also look more closely at the data, Mato Grasso doesn’t look much warmer. In fact, the southern half of Illinois, which has average yields comparable to those in Mato Grasso, also has comparable exposure to extreme heat. (Northern Illinois is cooler and higher yielding than both Mato Grasso and Illinois). This can be seen from careful inspection of the maps below (click the figure for more detail). It turns out that there aren’t any soybeans grown in the hottest part of Mato Grasso. It’s not clear whether the commenters took into account the locations in Mato Grasso where soybeans are actually grown.

Anyway, we couldn’t include figures or appendices in our 500 word reply to the comment, so we posted a short article on SSRN with more detail (see here). The actual comment and reply should show up at PNAS soon.

Boy, that was fast.

Less than three weeks after PNAS published Wolfram Schlenker’s and my paper predicting big negative impacts from global warming on U.S. corn, soybean and cotton yields, we were notified about a letter to the editor commenting on our article. The PNAS editors had already agreed to publish the letter when they told us about it. We had seven days to write a maximum 500-word reply.

The jist their letter: It’s already hotter in Brazil than the United States, and some areas of Brazil have higher yields than the United States, so we were being too “pessimistic” about what might happen to U.S. yields. More precisely, they claimed 2008 soybean yields in the Brazilian state of Mato Grasso were higher than U.S. yields of that year.

Hmmmm. Well, we didn’t claim our results extended to Brazil. Brazil differs from the U.S. in many ways. For one, Brazil is a lot closer to the equator, which makes sunlight exposure markedly different. Both countries are also quite large. The U.S., like Brazil, has widely varying temperatures and crop yields. So, to our way of thinking, such a comparison really deserves more careful thought and analysis than a drive-by letter to the editor.

We didn’t understand the statistics given by the commenters, so we did a little digging of our own. Mind you, we didn’t have time for a full-blown study. But here’s what we found:

First, they cherry picked the state and the year from Brazil. Mato Grasso is the highest yielding state in Brazil and 2008 was a remarkably good year for them, due to unusually good weather. Other states in Brazil have average yields that are about half those of Mato Grasso.

Second, Mato Grasso yields were higher than average yields in the U.S. as a whole, but not higher than the best yielding states in the U.S.

Third, if we narrow our comparison by looking a particular state—Illinois, the number two yielding soybean state in the U.S.—and also look more closely at the data, Mato Grasso doesn’t look much warmer. In fact, the southern half of Illinois, which has average yields comparable to those in Mato Grasso, also has comparable exposure to extreme heat. (Northern Illinois is cooler and higher yielding than both Mato Grasso and Illinois). This can be seen from careful inspection of the maps below (click the figure for more detail). It turns out that there aren’t any soybeans grown in the hottest part of Mato Grasso. It’s not clear whether the commenters took into account the locations in Mato Grasso where soybeans are actually grown.

Anyway, we couldn’t include figures or appendices in our 500 word reply to the comment, so we posted a short article on SSRN with more detail (see here). The actual comment and reply should show up at PNAS soon.

Friday, October 9, 2009

Optimal contracts for jumped-up monkeys

Amid the serious health care debate we have Brad Delong responding to Marty Feldstein with:

But seriously, if we're all jumped-up monkeys (and let's face it, many of us are) forget the copay on preventative care. In fact, wouldn't it be more profitable if insurance companies paid patients for preventative-care visits? Once upon a time I would have swallowed the prima facie evidence that insurance companies don't pay for prevention as proof such a policy wasn't optimal. I suppose I still lean in that direction. But I'm not so sure...

...[P]eople are really lousy consumers of medical services when they have to spend their own nickel. Why, just this morning Anthem Blue Cross waived the copays on all flu shots. That's not something you would want to do if people were anything more than jumped-up monkeys with brains designed to figure out whether the fruit is ripe..Which made me laugh very hard...

But seriously, if we're all jumped-up monkeys (and let's face it, many of us are) forget the copay on preventative care. In fact, wouldn't it be more profitable if insurance companies paid patients for preventative-care visits? Once upon a time I would have swallowed the prima facie evidence that insurance companies don't pay for prevention as proof such a policy wasn't optimal. I suppose I still lean in that direction. But I'm not so sure...

Thursday, October 8, 2009

IFPRI Report on Climate Change and Food

IFPRI came out with a big report that, like our study, also predicts pretty dismal outcomes for crop yields. Here's a nice summary and link to the report:

Wolfram Schlenker and I are more "raw data" kind of folks and are nowhere near ready to make these kinds of broader predictions. But I do know these guys at IFPRI have been working hard on this stuff for a long time. Awhile back I presented our work at IFPRI and for awhile they seemed interested in our statistical approach to modeling yields. But ultimately I guess they found that for many countries it's hard to get the necessary high-quality data.

I can't claim to understand the details of their model. But from what I do know, their results smell about right to me...

Funny, it wasn't that long ago everyone was saying that, for the world as a whole, climate change would be a wash and maybe even good for agriculture. What's changed? Three key things:

1) A lot less optimism about the positive effects of CO2 fertilization.

2) A greater appreciation for the detrimental effects of extreme heat.

3) Steadily worsening predictions for the amount of warming that will take place.

This analysis brings together, for the first time, detailed modeling of crop growth under climate change with insights from an extremely detailed global agriculture model, using two climate scenarios to simulate future climate. The results of the analysis suggest that agriculture and human well-being will be negatively affected by climate change:There are a lot of differences between what IFPRI did and what we did. At its core, the IFPRI uses crop simulation models developed and used by agronomists. We looked at the raw data and did everything from scratch. IFPRI also looked at the whole world where we looked at just the U.S.. IFPRI then combined the agronomics with a lot of complicated economic modeling, and went on to predict price responses an adaptation effects.

- In developing countries, climate change will cause yield declines for the most important crops. South Asia will be particularly hard hit.

- Climate change will have varying effects on irrigated yields across regions, but irrigated yields for all crops in South Asia will experience large declines.

- Climate change will result in additional price increases for the most important agricultural crops–rice, wheat, maize, and soybeans. Higher feed prices will result in higher meat prices. As a result, climate change will reduce the growth in meat consumption slightly and cause a more substantial fall in cereals consumption.

- Calorie availability in 2050 will not only be lower than in the no–climate-change scenario—it will actually decline relative to 2000 levels throughout the developing world.

- By 2050, the decline in calorie availability will increase child malnutrition by 20 percent relative to a world with no climate change. Climate change will eliminate much of the improvement in child malnourishment levels that would occur with no climate change.

- Thus, aggressive agricultural productivity investments of US$7.1–7.3 billion are needed to raise calorie consumption enough to offset the negative impacts of climate change on the health and well-being of children.

Authors: Nelson, Gerald C., Rosegrant, Mark W., Koo, Jawoo, Robertson, Richard

Sulser, Timothy, Zhu, Tingju, Ringler, Claudia, Msangi, Siwa, Palazzo, Amanda

Batka, Miroslav, Magalhaes, Marilia, Valmonte-Santos, Rowena, Ewing, Mandy

Lee, David

Wolfram Schlenker and I are more "raw data" kind of folks and are nowhere near ready to make these kinds of broader predictions. But I do know these guys at IFPRI have been working hard on this stuff for a long time. Awhile back I presented our work at IFPRI and for awhile they seemed interested in our statistical approach to modeling yields. But ultimately I guess they found that for many countries it's hard to get the necessary high-quality data.

I can't claim to understand the details of their model. But from what I do know, their results smell about right to me...

Funny, it wasn't that long ago everyone was saying that, for the world as a whole, climate change would be a wash and maybe even good for agriculture. What's changed? Three key things:

1) A lot less optimism about the positive effects of CO2 fertilization.

2) A greater appreciation for the detrimental effects of extreme heat.

3) Steadily worsening predictions for the amount of warming that will take place.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Renewable energy not as costly as some think

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The other day Marshall and Sol took on Bjorn Lomborg for ignoring the benefits of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed. But Bjorn, am...

-

The tragic earthquake in Haiti has had me wondering about U.S. Sugar policy. I should warn readers in advance that both Haiti and sugar pol...

-

A couple months ago the New York Times convened a conference " Food for Tomorrow: Farm Better. Eat Better. Feed the World ." ...